JINDO, South Korea — One by one, coast guard officers carried the newly arrived bodies covered in white sheets from a boat to a tent on the dock of this island, the first step in identifying a sharply rising number of corpses from a South Korean ferry that sank nearly a week ago.

Dozens of police officers in neon green jackets formed a cordon around the dock as the bodies arrived Tuesday. Since divers found a way over the weekend to enter the submerged ferry, the death count has shot up. Officials said Tuesday that confirmed fatalities had reached 104, with nearly 200 people still missing.

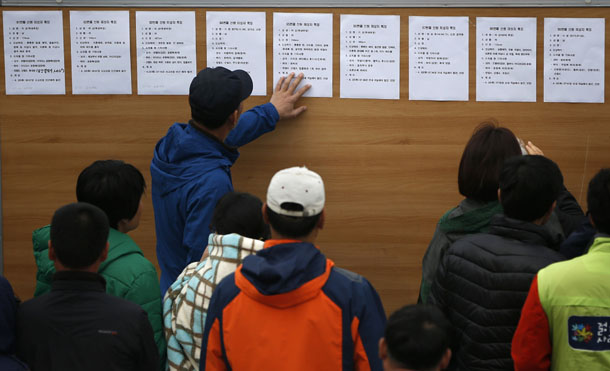

If a body lacks identification, details such as height, hair length and clothing are posted on a white signboard for families waiting on Jindo island for news.

The bodies are then driven in ambulances to two tents: one for men and boys, the other for women and girls. Families listen quietly outside as an official briefs them, then line up and file in. Only relatives are allowed inside.

For a brief moment there is silence. Then the anguished cries, the wailing, the howling. They have not known for nearly a week whether they should grieve or not, and now they sound like they’re being torn apart.

“How do I live without you? How will your mother live without you?” a woman cries out.

She is with a woman who emerges from a tent crying and falls into a chair where relatives try to comfort her. One stands above her and cradles her head in her hands, stroking her face.

“Bring back my daughter!” the woman cries, calling out her child’s name in agony. A man rushes over, lifts her on his back and carries her away.

This heartbreak still awaits many families of those still missing from the submerged ferry Sewol, or at least those whose relatives’ bodies are ultimately recovered. Families who once dreamed of miraculous rescues now simply hope their loved ones’ remains are recovered soon, before the ocean does much more damage.

“At first, I was just very sad, but now it’s like an endless wait,” said Woo Dong-suk, a construction worker and uncle of one of the students. “It’s been too long already. The bodies must be decayed. The parents’ only wish right now is to find the bodies before they are badly decomposed.”

About 250 of the more than 300 missing or dead are students from a single high school, in Ansan near Seoul, who were on their way to the southern tourist island of Jeju.

Bodies are being identified visually, but family members have been providing DNA samples in case decomposition makes that impossible.

The families, and South Koreans more broadly, have at times responded with fury. The captain initially told passengers to stay in their rooms and waited more than half an hour to issue an evacuation order as the Sewol sank. By then, the ship had tilted so much it is believed that many passengers were trapped inside.

At a Cabinet briefing Monday, President Park Geun-hye said, “What the captain and part of the crew did is unfathomable from the viewpoint of common sense. Unforgivable, murderous behavior.” The comments were posted online by the presidential Blue House.

The captain, Lee Joon-seok, and two crew members have been arrested on suspicion of negligence and abandoning people in need, and prosecutors said Monday that four other crew members have been detained. On Monday night, prosecutors requested a court to issue a warrant to formally arrest these four people, a prosecution office said in a release late Monday.

A transcript of ship-to-shore communications released Sunday revealed a ship that was crippled with indecision. A crew member asked repeatedly whether passengers would be rescued after abandoning ship even as the ferry tilted so sharply that it became impossible to escape.

Lee, 68, has said he waited to issue an evacuation order because the current was strong, the water was cold and passengers could have drifted away before help arrived. But maritime experts said he could have ordered passengers to the deck—where they would have had a greater chance of survival—without telling them to abandon ship.

Emergency task force spokesman Koh Myung-seok said bodies have mostly been found on the third and fourth floor of the ferry, where many passengers seemed to have gathered. Many students were also housed in cabins on the fourth floor, near the stern of the ship, Koh said.

The cause of the disaster is not yet known, and only became murkier Tuesday, when a South Korean official said the ferry had not taken an unusually sharp turn shortly before the sinking as had been initially believed.

Data from the Sewol’s automatic identification system, an on-board transponder used for tracking, shows that the ship made a J-shaped turn before listing heavily and ultimately sinking.

A ministry of ocean and fisheries official had said Friday that the vessel had taken a sharp turn. But on Tuesday a ministry official said in a phone interview that the AIS data had been incomplete. He says the true path of the ship became clear when the data was fully restored.

The official declined to elaborate or give his name, but provided a map that showed both the hard 115-degree turn originally estimated and the more gradual path the restored data describes.

It remains unclear why the ship turned around shortly before it sank. The third mate, who has been arrested, was steering at the time of the accident, in a challenging area where she had not steered before, and the captain said he was not on the bridge at the time.

Authorities have not identified the third mate, though a colleague identified her as Park Han-gyeol. Senior prosecutor Ahn Song-don said Monday the third mate has told investigators why she made the turn, but he would not reveal her answer, and more investigation is needed to determine whether the answer is accurate.

Most of the bodies found have been recovered since the weekend, when divers, frustrated for days by strong currents, bad weather and poor visibility, were finally able to enter the ferry. But conditions remain challenging.

“I cannot see anything in front … and the current underwater is too fast,” said Choi Jin-ho, a professional diver who searched the ferry Monday. “Then breathing gets faster and panic comes.”

Associated Press writers Hyung-jin Kim in Mokpo, South Korea, Minjeong Hong and Raul Gallego in Jindo, and Foster Klug, Youkyung Lee, Jung-yoon Choi and Leon Drouin-Keith in Seoul contributed to this report.