BHOPAL / NEW DELHI, India — Beyond the iron gates of the derelict pesticide plant where one of the world’s worst industrial disasters occurred, administrative buildings lie in ruins, vegetation overgrown and warehouses bolted.

Massive vessels, interconnected by a multitude of corroded pipes that once carried chemical slurries, have rusted beyond repair. In the dusty control room, a soiled sticker on a wall panel reads “Safety is everyone’s business.”

On the night of Dec. 2, 1984, the factory owned by the US multinational Union Carbide Corp accidentally leaked cyanide gas into the air, killing thousands of largely poor Indians in the central city of Bhopal.

Thirty years later, the toxic legacy of this factory lives on, say human rights groups, as thousands of tonnes of hazardous waste remains buried underground, slowly poisoning the drinking water of more than 50,000 people and affecting their health.

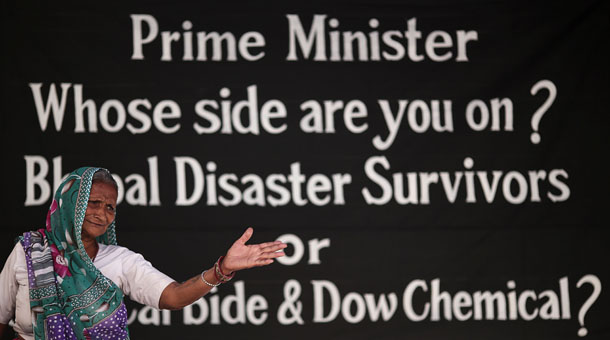

Activists want this waste removed and disposed of away from the area, and feel Indian authorities, who now own the site, have fumbled on taking action—either by clearing up the waste itself or in pursuing Union Carbide to take responsibility.

“There is a very high prevalence of anemia, delayed menarche in girls and painful skin conditions. But what is most pronounced is the number of children with birth defects,” said activist Satinath Sarangi from the Bhopal Medical Appeal which runs a clinic for gas victims.

“Children are born with conditions such as twisted limbs, brain damage, musculoskeletal disorders… this is what we see in every fourth or fifth household in these communities.”

Sarangi admits there has been no long-term epidemiological research which conclusively proves that birth defects are directly related to the drinking of the contaminated water.

Toxic Water

Built in 1969, the Union Carbide plant in Madhya Pradesh state was seen as a symbol of a new industrialized India, generating thousands of jobs for the poor and, at the same time, manufacturing cheap pesticides for millions of farmers.

Fifteen years later, 40 tonnes of Methyl Isocyanate gas was released and carried by the wind to the surrounding densely populated area, and the extent of the disaster remains unclear and under debate.

The government recorded 5,295 deaths, but activists claim 25,000 people died in the aftermath and following years.

Another 100,000 people who were exposed to the gas continue to suffer today with sicknesses such as cancer, blindness, respiratory problems, immune and neurological disorders. Some children born to survivors have mental or physical disabilities.

While those directly affected receive free medical health care, activists say authorities have failed to support those sick from drinking the contaminated water and a second generation of children born with birth defects.

In a rehabilitation centre run by the charity Chingari Trust, located 500 meters from the factory site, disabled children aged between 6 months and 12 years gather for treatment which ranges from speech and hearing issues to physiotherapy.

“Our life changed emotionally and physically since we got to know about his medical problem when he was just 4 months old,” said 26-year-old Sufia, sitting on a mat on the floor, cradling her two-year-old son Mustafa who has cerebral palsy.

“We had to stop the therapy when he was 8-months-old as it was very expensive. My husband is an electrician and doesn’t earn much. With the center it is good as it’s free. It’s also good to meet other mothers with their children and realize that I am not alone.”

Call For Clean-Up

The government was forced to recognize that the water was contaminated in 2012 when the Supreme Court ordered that clean drinking water be supplied to some 22 communities living around the factory site.

“I don’t think there is any doubt now that the waste dumped by Union Carbide is a serious problem and that it needs to be dealt with urgently,” said Sunita Narain, director of the Delhi-based think-tank Center for Science and Environment.

Studies by Narain’s organization in 2009 found samples taken from around the factory site contained chlorinated benzene compounds and organochlorine pesticides 561 times the national standard.

The profile of the chemicals found in samples from within the site matched the chemicals in drinking water in the outside colonies, said the report, leaving no doubt that there could be no other source of these toxins than Union Carbide.

Studies since have confirmed water pollution, but the hazardous waste remains in pits in some 21 locations within the 68-acre site and buried in a wasteland outside, largely due to wrangles between authorities and activists on its disposal.

The United Nations this week welcomed a government decision to reconsider the official figure of people affected by the gas leak, and look into additional compensation, but pressed authorities to get rid of the toxic waste.

“New victims of the Bhopal disaster are born every day, and suffer life-long from adverse health impacts,” said Baskut Tuncak, UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and toxic waste.

“Without cleaning the contamination, the number of victims of the toxic legacy left by Union Carbide will continue to grow, and, together, India’s financial liability to a rising number of victims,” he added in a statement.

Activists want Union Carbide, which was taken over by Dow Chemical Company in 2001, to take the waste out of the country, saying there are no adequate facilities in India to deal with it. They have also criticized state authorities for not pursuing the corporation for the clean-up. State government officials were not immediately available for comment.

Seventeen people living around the plant have filed a petition in the US courts to get the multinational to bear the cost of the clean-up.

Dow Chemical Co. has long denied responsibility, saying Union Carbide spent US$2 million on remediating the site, adding that Indian authorities at the time approved, monitored and directed every step of the clean-up work.

Union Carbide was sued by the Indian government after the disaster and agreed to pay an out-of-court settlement of $470 million in damages in 1989. The company says the Indian government then took control of the site in 1998, assuming all accountability, including clean-up activities.

“While Union Carbide continues to have the utmost respect and sympathy for the victims, we find that many of the issues being discussed today have already been resolved and responsibilities assigned for those that remain,” Tomm F. Sprick, Director of Union Carbide Information Center, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in an email.