On June 30, the military regime released over 2,000 people who had been detained over the past five months for their involvement in the anti-junta movement.

Most of those freed were civilians detained in anti-regime protests, as well as 12 journalists. The Irrawaddy has interviewed some of the freed journalists about how they were arrested and their experiences in prison.

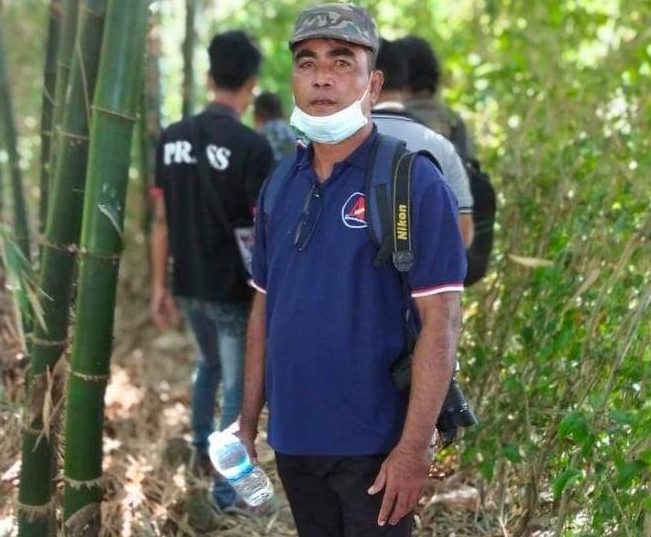

Ko Aung Mya Than

Reporter, Ayeyarwaddy Times

Eight junta vehicles surrounded my house and I was taken away for interrogation. I was beaten. They punched me in my ribs, face and mouth and slapped my face. Around eight drunken soldiers interrogated me, while accusing journalists of making false reports.

I challenged [the military] in a Facebook live on the day of the coup [on Feb. 1]. So they had a grudge against me and beat me while interrogating me for challenging them. At first, I was questioned at Maubin Police Station [in Maubin Township, Ayeyarwady Region]. My face got swollen and my mouth was terribly bruised [from the beatings]. I was not allowed to sleep that night and the whole of the next day. In fact, it was a beating rather than an interrogation as I had challenged them [on Facebook live]. Seven [soldiers] beat me and they didn’t even give me water.

Two days after my arrest, I was taken to Light Infantry Battalion 27 and interrogated again. I was not beaten there. After questioning, I was placed in solitary confinement at Maubin Prison until I was released.

I was detained for one month and 19 days and I was kept in solitary confinement throughout my detention, except for three days in a prison cell with others. It appears that I have suffered some internal injuries. I am afraid that I will suffer from the effects of the torture later in my life. For now, I am fine except for frequent dizziness.

In prison, detainees charged under 505(a) [incitement charge] were not tortured. It was only during interrogations that detainees were tortured. Even the police could not interfere. They [soldiers] were pretending to be police. Among them [those who interrogated me] were people from the special branch [of police], the military security affairs office and soldiers. Most of them were soldiers. They did the interrogations. Police could not interfere and had to do what they were told by the soldiers. They [the military] are overstepping their authority.

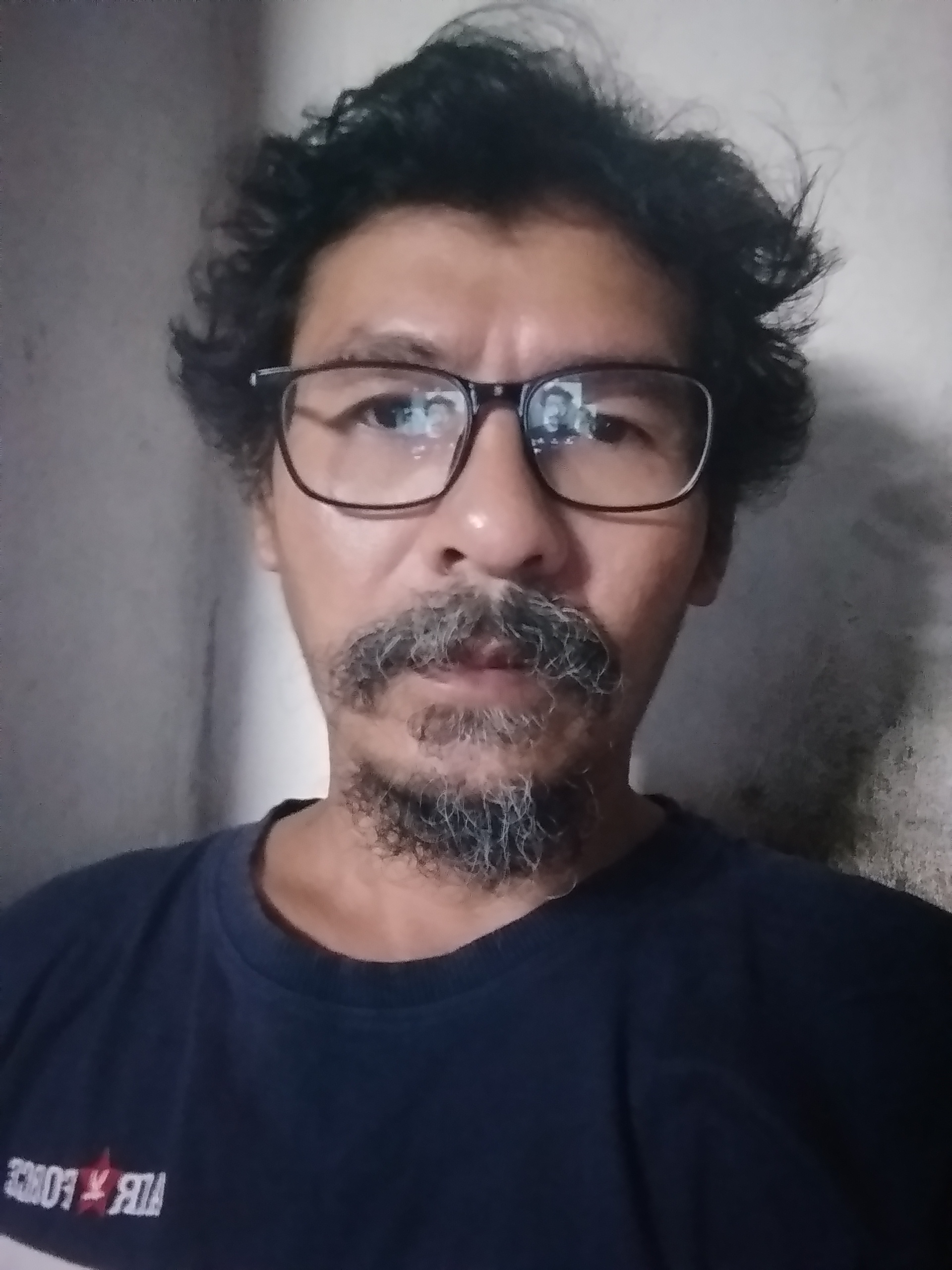

Ko Zin Thaw Naing

Editor, Democracy Vision

I was arrested by police from Botahtaung Police Station in Yangon and was taken to the police station. I was put into a cell and then a military officer questioned me. I was beaten and punched that night while I was being interrogated. I was remanded in custody the following day and the police took me to the prison for fear that something might happen to me at the police station.

I was not sent to an interrogation center. They had already filed a lawsuit against me for swearing at the coup leader before I got arrested. They got nothing from my phone when I was arrested. So they were not able to file a new charge and only charged me for swearing.

Frankly speaking, as they have our personal information, they can arrest us any time they want. We were freed, but it is like moving from a small prison to a bigger one. They can arrest us at any time for any excuse.

Ko Banyar Oo

Freelance Journalist

I was sent straight to prison. I was questioned by the police at the prison. I was not beaten during the interrogation. Normally, people who were interrogated [at a police station or interrogation center] before being sent to prison were beaten. The food they gave us inside the prison was not OK. It was lousy and could hardly be called rice and curry. They gave us lectures to suppress our morale and, as we refused to obey prison rules, they put us in solitary confinement.

Altogether seven journalists were placed in solitary confinement and sent to the main jail. There is a room in which prisoners are forced to squat in the stress position. We were taken to that room and asked to squat in the stress position. We had an argument as we told them not to treat political prisoners that way. Then, the other political prisoners who were already squatting there joined the argument, which lead to a clash. We were then sent to a criminal prisoners’ wing as a punishment for instigating the argument. We spent 18 days there.

Although we were not beaten, we were threatened with solitary confinement if we talked to each other. It was a violation of our human rights. They didn’t set conditions for our release. But we have concerns that they may arrest us if there are bomb explosions or arson attacks near our homes. So I feel unsafe.

Ko Soe Yarzar Tun

Freelance Journalist

At Insein Prison the correctional department staff sat on chairs as they interrogated us, while we were told to sit on the floor. They attempted to suppress the political prisoners by doing that. There were 80 people in my cell and, around two days later, they selected four including me and put us in solitary confinement. I think I was in solidarity confinement for one day and one night.

At first, I could make phone calls through the police. Then, I could not contact my family for the next two months. Later, at the trial, I could contact them by using my lawyer’s phone. We were not tortured like political prisoners were tortured in the past, but they punished us for not obeying prison rules. We didn’t have to negotiate with prison authorities to get released.

The police only swore at me a little when I got arrested and did nothing to me. The following day, I was sent to an interrogation center. I was not beaten there either. The prison was too overcrowded. As more detainees came, there were more than 80 people per cell and we had to sleep on our sides as there was no room to lie flat.

There were no significant human rights violations against those charged under Article 505(a). But around half of the detainees on each wing were sick. On June 28, some 15 people arrived in the prison after being interrogated. Three of them were very sick and suspected of having COVID-19. The three were placed in solitary confinement and the others were placed in a separate cell. There is a clinic inside the prison which gave out medicine. I am concerned that I might be arrested again for no reason. I have to be more careful as I was arrested even though I didn’t do anything wrong.

Ko Ye Myo Khant

Photojournalist (Myanmar Pressphoto Agency)

I was not beaten when I was arrested. But I was threatened and pressured to confess that I had violated journalist ethics by protesting against the coup and also that I had incited people to protest. I was sent straight to prison and was not taken to an interrogation center.

There were human rights violations against political prisoners while we were in prison. [Prison staff] treated political prisoners more harshly than those who committed other crimes. Those under pretrial detention didn’t have to do labor. But those who were convicted under Article 505(a) had to do some labor at the main jail. I was not beaten in prison.

Young people under 18 years were detained for a long time in prison. So were sick and elderly persons. I saw at least three people who died in prison after falling sick.

You may also like these stories:

As COVID-19 Spreads, Thai Govt Stuck in Self-Made Trap

At Least 25 Civilians Killed in Shootout with Myanmar Junta

Myanmar Junta Chief Extols Russia Ties, Says US Relations ‘Not Intimate’