MOULMEIN, Mon State — The village of Inn Din is green and lush with rubber, durian and betel plantations, as well as an opening to the Andaman Sea and its fishery resources to the west.

However, the village has been haunted by a proposed coal-fired power plant, often described locally as a “silent killer.”

“We have been living on this land for generations and we want to pass it on to our descendants. I do not want this project built on our land,” said local villager U Aung, whose farmland is located within the project area.

Local villagers have dreaded the health risks of the coal-fired plant since April 2014 when the Toyo-Thai Public Co Ltd (TTPCL), a Thai-Japan consortium, chose a site for the 1,280-megawatt power plant near the village.

The company signed a memorandum of understanding with former Burmese President U Thein Sein’s government on April 9, 2015 to build the power plant at a cost of US$2.8 billion.

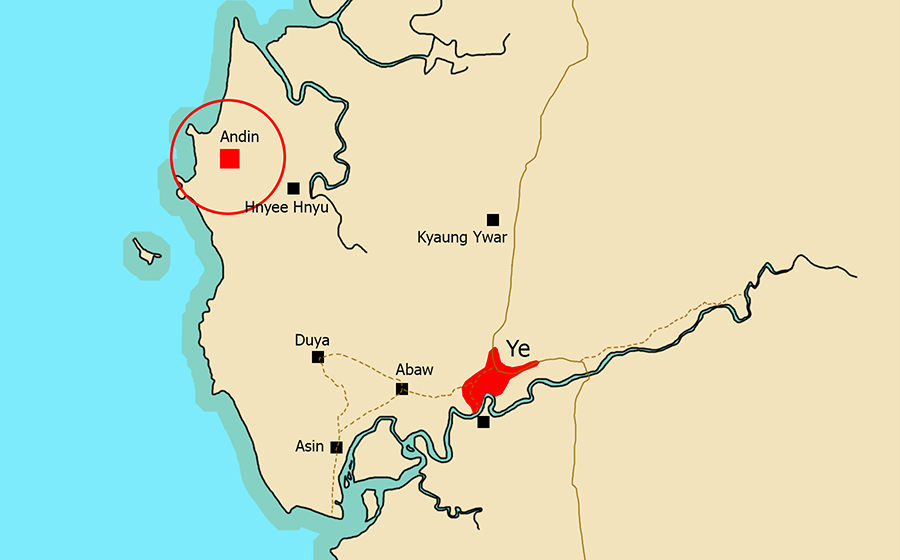

The project site is just two kilometers from Mon State’s Inn Din Village. Toyo-Thai Co has earmarked 500 acres of lands for the power plant, and has also proposed building a pontoon bridge, which would be three to five kilometers long and stretch into the Andaman Sea.

Local villagers do not know the extent of possible environmental impacts but fear that the plant will adversely impact their livelihoods by affecting fishing and farming.

Villagers from several nearby villages share the same concerns. On May 5, 2015, over 5,000 locals from seven villages staged a protest against the project.

Montree Chantawong, an ecologist at the Toward Ecological Recovery and Regional Alliance (TERRA), a Thai-based environmental organization that has been providing technical assistance to Inn Din villagers, told The Irrawaddy that the organization found a rare crab species.

“We documented plants, aquatic animals and birds in the region, and also held talks with the marine biology department of Moulmein University on the aquatic animals we discovered and documented,” he said.

According to the organization’s survey in seven villages including Inn Din over the past three years, it found 26 plant species, 71 bird species, 138 fish species, 15 prawn species, and seven crab species.

Amid the mounting opposition, U Kyaw San Win, director of a civil society organization known as the National Enlightenment Institute (NEI), visited the village along with a foreign expert to conduct an independent survey on the geology and ecosystem of the project area in July 2015.

“During our visit with the local abbot prior to visiting the project site, villagers gathered, banged pots and pans, and shouted for us to leave. I think the whole village came out,” he said.

While most villagers object to the project, some silently expect to sell their land for high profits but dare not be vocal about their support.

“We don’t want this project. We earn enough money from farming to feed our families and send our children to university,” villager U Lay Lin told The Irrawaddy.

Most of the villagers share his view. They do not want to risk their livelihoods for a power plant when they have lived off of the electricity grid to this point.

Currently, the village only has electricity for a few hours at night from a diesel generator arranged by the village monastery abbot.

Locals went to the Japanese Embassy in Rangoon to file a petition against the project. They also filed a petition to Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which are providing loans to Toyo-Thai Co.

They also turned down regional development incentives offered by the company in connection with the project. Instead, they concreted the main village road with their own money.

As the project is mainly intended to provide electricity for the Thilawa SEZ, the villagers may get some of the electricity, but it is not fair when compared with the burden of negative impacts it will bring them, said Montree Chantawong.

The company has said it would bring in thousands of foreign technicians when it started construction. Villagers are also concerned about possible social and cultural impacts on their village which currently only has a population of some 2,800 people.

In 2015, the company employed Vietnamese technicians to conduct a feasibility survey for the pontoon bridge. The technicians lived in floating houses but minor tensions between the two sides still arose.

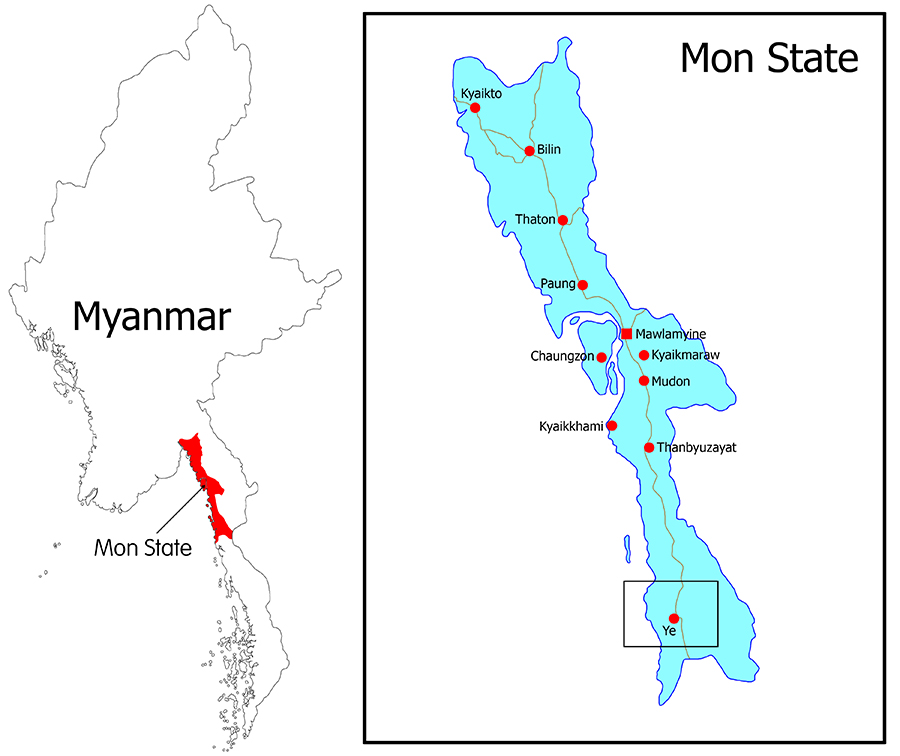

From 2013 to 2015, there were several confrontations between the company and the villagers, and in June 2015, the company filed complaints with the Ye Township police station against 20 villagers. But, 300 villagers went to the police station and defended them and the case was later settled.

The company highlights the low production cost of electricity in its calculations, but does not mention the damages to be caused by the project, said Areeya Tivasuradej, an ecologist at TERRA.

“Now, we can eat prawns from the sea, trade them and hand down to the next generation. In calculating its investment, the company did not include the loss to be caused by a decline in production [of fishery products as a result of the power plant],” she said.

On June 8, 2014, Dr. Aung Naing Oo, a Mon State lawmaker representing Chaungzon Township and chairman of the Mon State parliamentary committee that reviews laws, proposals, questions, and regional plans, visited Inn Din Village to hear from the villagers. Locals cast a secret vote during his visit, resulting in 206 against, four in favor, and six abstentions.

On Sept. 5, 2014, the Mon State government instructed the Toyo-Thai Co not to continue the project’s feasibility study.

On Dec. 30, 2015, in response to a question in the Lower House from lawmaker Mi Myint Than about the project, deputy minister for electricity U Aung Than Oo said the feasibility study had been suspended.

The Toyo-Thai Public Co holds shareholder meetings every April and later submits its annual report to shareholders, said Montree Chantawong.

According to this year’s report, the company told shareholders that the project was shelved, Montree Chantawong told The Irrawaddy.

This is the first time the company has announced its suspension of the project to shareholders, he added.

However, it is a suspension and not a termination, villagers said, adding that they fear a resumption of the project and look at outsiders with suspicion.

If you go to the village for the first time with a foreigner, locals say you had better go straight to the village monastery and explain why you have come. They claim that the nightmare of the coal plant has stripped them of their hospitality.