Stalemate: Autonomy And Insurgency On The China-Myanmar Border

By Andrew Ong

Cornell University Press, 2023

US$29.95, 276 pages

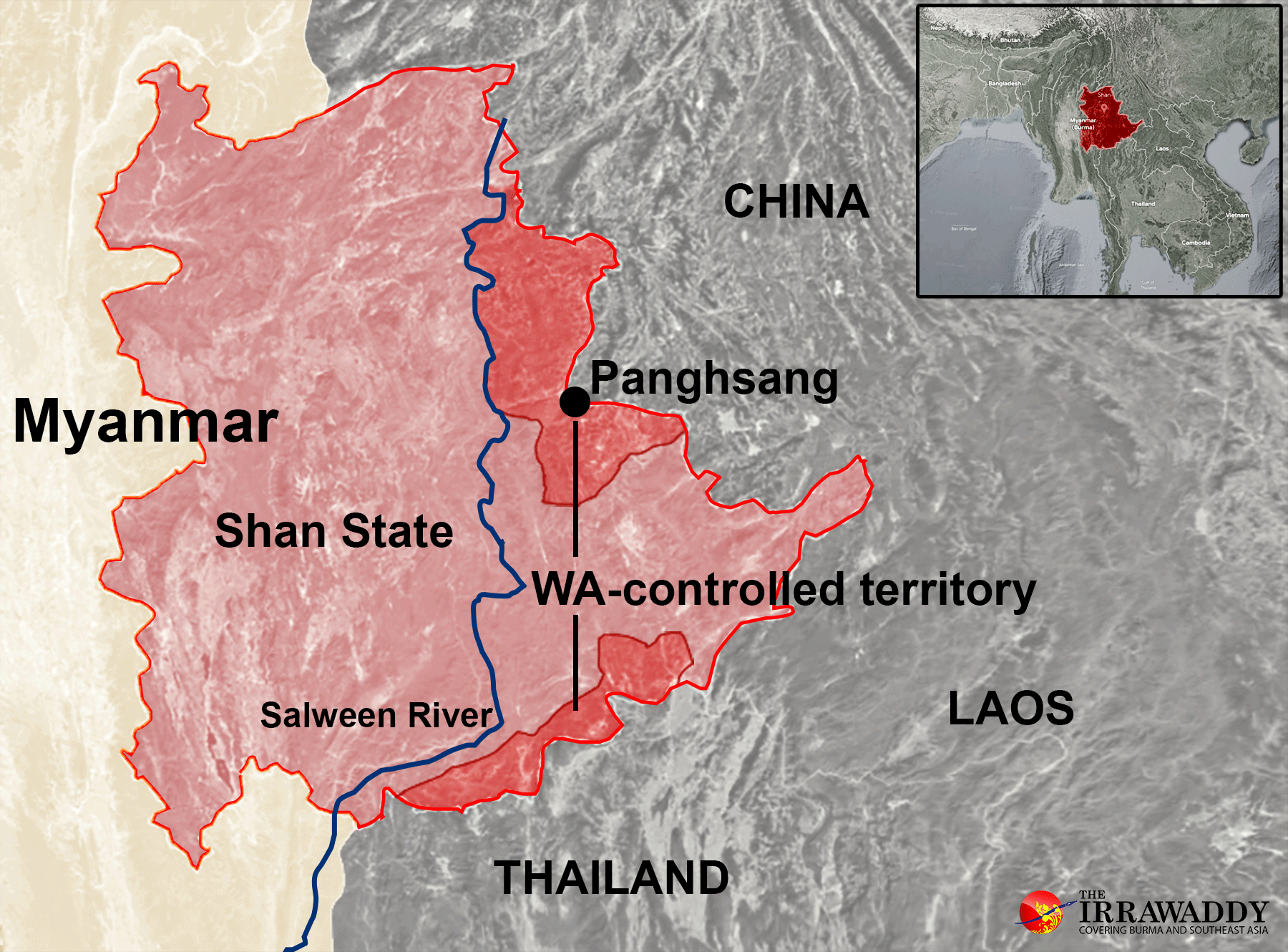

While civil war rages across many parts of Myanmar, there is one corner of the country which seems largely unaffected by the tragic developments following the 2021 military coup: the Wa Hills of northeastern Shan State. Andrew Ong’s excellent study of the Wa is therefore appropriately titled “Stalemate”, a word that could also be used to characterize the situation that has prevailed in that remote part of Myanmar since the military and the local, ethnic army entered into a ceasefire agreement in 1989. The United Wa State Party (UWSP) and its United Wa State Army (UWSA) have often been dismissed as narcotraffickers, and while that is not entirely inaccurate, they have also managed to build up a 20,000-sq-km de facto autonomous zone between Myanmar and China. The total population of the area is about 450,000, mostly Wa but also other nationalities such as Shan, Lahu, Akha and Chinese.

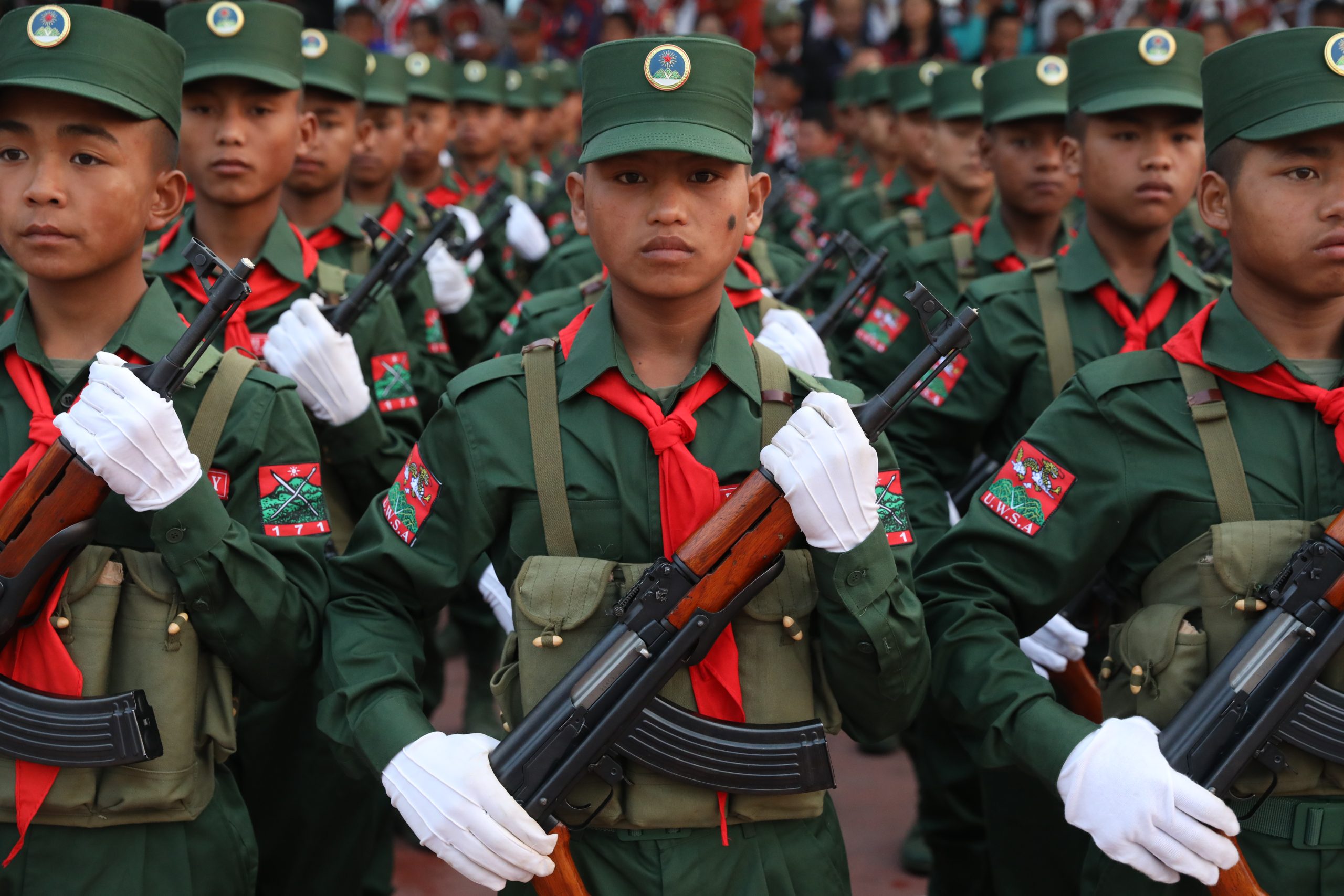

The Wa, a Mon-Khmer speaking people, have their own administration, which oversees courts, hospitals, schools, law enforcement agencies, trading companies—and, as scholar Magnus Fiskesjö writes in an endorsement, “Asia’s largest and most powerful ethnonationalist insurgent army.” The actual strength of the UWSA is a closely guarded secret, but independent observers believe it has between 20,000 and 30,000 heavily armed men under its command. Its arsenal consists of modern automatic rifles, machine-guns of all calibers, mortars, MANPADS or man-portable air-defense systems, artillery, military trucks, armored vehicles and even weaponized drones. Evidently, the UWSP/UWSA is a force that cannot be overlooked by having its role in local and regional geopolitics reduced to that of a criminal band or a bunch of outlaws.

Having worked for several years for the World Food Program in the Wa Hills, Ong, a Singaporean anthropologist, is in a unique position to write about the political cultures of local elites and people. This trailblazing book is the first to describe the complexity of the UWSA and its allies, and their relationships with the Myanmar military—and the authorities across the border in China. Other recent books about the Wa include Fiskesjö’s Stories From an Ancient Land: Perspective on Wa History and Culture and my own The Wa of Myanmar and China’s Quest for Global Dominance, but Ong’s study covers a wider range of issues and was also written post-coup and explains why the UWSA, as he puts it, “remained outside the fray… In Wa Region, located on the border with China, the Chinese currency, language, and mobile networks are predominantly used, and the polity is far closer economically and politically to China than to Myanmar.” As a consequence, “the UWSA has had a strangely ambivalent history of political relations with its neighbors.”

The Treasury Department in Washington has blacklisted the top leaders of the UWSA for their alleged involvement in the Golden Triangle drug trade along with promises of million-dollar rewards to anyone who could bring them to trial, presumably in the United States. Ong argues that the UWSA is one of the most poorly understood armed groups in Southeast Asia. It is undeniable that the UWSA built its present strength mainly on proceeds from the drug trade, first in opium and heroin and later in ya ba, or methamphetamine. But it is also important to understand and analyze what got the Wa into that situation, and how they now, at least in the areas they control along the Chinese border (the situation is different along the border with Thailand, where the UWSA also has a string of bases and newly established civilian settlements) have substituted income from the drug trade with that from tin and rare earth mining and the cultivation of tea and rubber. There has also been significant Chinese investment in construction activities, real estate and the cross-border trade in all kinds of consumer goods destined for government-controlled areas in central Myanmar and as far as northern Thailand.

The uniqueness of the Wa Hills—which the Wa prefer to call “Wa State”, although there is officially no such state in the Union of Myanmar—is a direct outcome of the fact that the area now controlled by the UWSA has never been under the jurisdiction of any central authority. In ancient times, Ong writes, “warfare, constant raiding, and headhunting between neighboring Wa realms and villages created fortified villages as autonomous polities, resisting unification under a single chieftain or king, or the emergence of hierarchical political structures.” During the British time, colonial presence consisted of little more than a few field officers on the outskirts of the Wa Hills, and occasional flag marches up to the border to show the Chinese where their designated territory supposedly ended. After independence in 1948, the Wa Hills were ruled by local chieftains and warlords, and, in some parts, remnants of Nationalist Chinese, or Kuomintang, forces that had retreated across the border after being defeated by Mao Zedong’s communists during the Chinese Civil War, which ended in 1949.

Then, in the early 1970s, the Wa Hills were taken over by the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), which established a base area covering most of the border mountains. In 1989, the rank-and-file of the CPB’s army, which included thousands of Wa fighters, mutinied against the party’s ageing, staunchly Maoist leadership and drove them into exile in China. That was when the UWSP and the UWSA were established and, for the first time in history, the Wa Hills became ruled by a central, indigenous authority.

Ong’s study contains numerous interviews with people from all walks of life in the UWSP/UWSA-administered area, which shed new light on how they look at their situation as well as their relationships with Myanmar and China. The relationship between the UWSP/UWSA and Chinese entities, ranging from the security services to private companies, may be closer than that with actors in the rest of Myanmar. The UWSA’s impressive arsenal also originates in China. But all that doesn’t make the Wa stooges of the Chinese. Ong notes that “everyday resentment of exploitative and opportunistic Chinese economic influence, and the condescending attitudes of Chinese entrepreneurs and business surfaced occasionally among locals: ‘They are very arrogant, but their mouth is sweet. They know how to flatter’.” The “ambivalent Wa-China relationship was deeply embedded in tropes from Chinese narratives disparaging non-Han ethnic minorities within its borders; Wa Region inhabitants were well aware of these prejudices.”

Ong also examines the relationship between the UWSA and other ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in Myanmar. The UWSA is a member of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), which was set up in 2017 to bring together seven EAOs which, at least in theory, are seeking to negotiate a settlement with the government (now junta) in Naypyitaw. Several of those groups, though, are engaged in heavy fighting with junta forces while the UWSA is not. But according to several local sources, the UWSA has been providing some resistance forces with arms and ammunition at the same time as it is honoring its now 34-year-long ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military. The Wa maintain links with the junta, the so-called State Administration Council, as well as the National Unity Government, which was set up by elected MPs and pro-democracy forces after the coup. That ambivalence cannot be understood without a thorough study of the Wa, and that is precisely what Ong has accomplished in his brilliant study of their polity, history and culture.

Although his book is mainly an academic, anthropological study, it should nevertheless be read by anyone interested in contemporary Myanmar, its multifaceted politics and seemingly never-ending ethnic conflicts. In order to find a way forward, it is absolutely essential to understand the background to today’s realities in the Wa Hills, and, as Ong concludes: “Observers have listed the UWSA as an EAO that adopts a ‘wait-and-see’ attitude, non-committal to either the State Administration Council or the National Unity Government. The UWSA remains committed first to its own autonomy, carefully balancing the relations between these two sides, as well as its ties with China. Understanding how the UWSA envisions its autonomy, and enacts it, is the first step to figuring out how to accommodate the Wa polity in a new Myanmar.”

Bertil Lintner is a Swedish journalist, author and strategic consultant who has been writing about Asia for nearly four decades.