LON TON, Kachin State — Face of Indawgyi is a sustainable social enterprise based at Indawgyi Lake in Kachin State. As well as facilitating sustainable, community-based tourism at the lake, Myanmar’s largest, the project works on four main principles: cultural preservation, environmental conservation, educational opportunities and sustainable business development.

The idea for Face of Indawgyi came during US-native Stephen Traina-Dorge’s visit to Lon Ton Village, on the southeast shore of the lake, while making a video documentary in 2015. He was struck by the tranquility of the lake, the open friendliness of the people and their unique culture.

“This really all stemmed out of cultural preservation. We were doing a cultural preservation documentary on thanaka and came here to document rural northern Myanmar. Right when we arrived, we felt the same thing — this place is incredibly special. We wanted to have more of an impact than the thanaka documentary work,” said Traina-Dorge.

In July 2017, he moved to Lon Ton and founded Face of Indawgyi. He was joined by a like-minded partner, Patrick Compton, also from the US, who became associate director.

Though over 70,000 pilgrims visit the lake annually for the festival at Shwemyitzu Pagoda, a temple that seems to float on the water’s surface, visitors to the lake strictly for tourism are few but growing. Travelers who do make their way here are drawn to the lake, part of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, for its wealth of birdlife and healthy populations of other endemic wildlife.

On a February morning at Indawgyi Motel, one of two basic guesthouses serving the lake in Lon Ton, Burmese, English, German, and Korean languages could be heard from visitors who, in their determination to experience this unique region, undertook the long journey to be here.

Tourism with and for the community

Face of Indawgyi helps to facilitate visits to the lake and in turn supports the community. It doesn’t focus on new activities or experiences, but rather connects visitors to a range of sustainable, community-focused activities that are already available but not widely known.

On a boat ride on the 260-square-km lake, you can see some of the 20,000 birds that flock here from Siberia each year to escape northern Russia’s harsh winters between November and March. You can join shrimp farmers on their wooden boats as they lay out their traps at dusk, the intricate cages dunked quietly into waters colored golden by the setting sun. Kayaks, bamboo bicycles and skateboards made from recycled plastic can be rented. Treks into the surrounding hills and various viewpoints by the lake are other low-impact activities that can bring financial income to local families.

Generating income locally and providing employment opportunities for the community’s youth are important positive social impacts of the project, which works in areas plagued by drug addiction and where many young men are lured into work at the notorious jade mines of Hpakant, 80 km away.

“In other places, it’s about being a tourist. But here, it’s about becoming involved in the community through your experiences,” said Traina-Dorge at a property on the lakeshore the social enterprise recently acquired and where it plans to build the Lon Ton Social Impact Guesthouse.

“We’re trying to make Indawgyi a kind of hub, an example for other places. We’re not trying to do it all ourselves. We’re looking for partnerships. If we could bring the best of 21st century ideas, the best of globalization, to solve local challenges, then that would be something special,” said Compton.

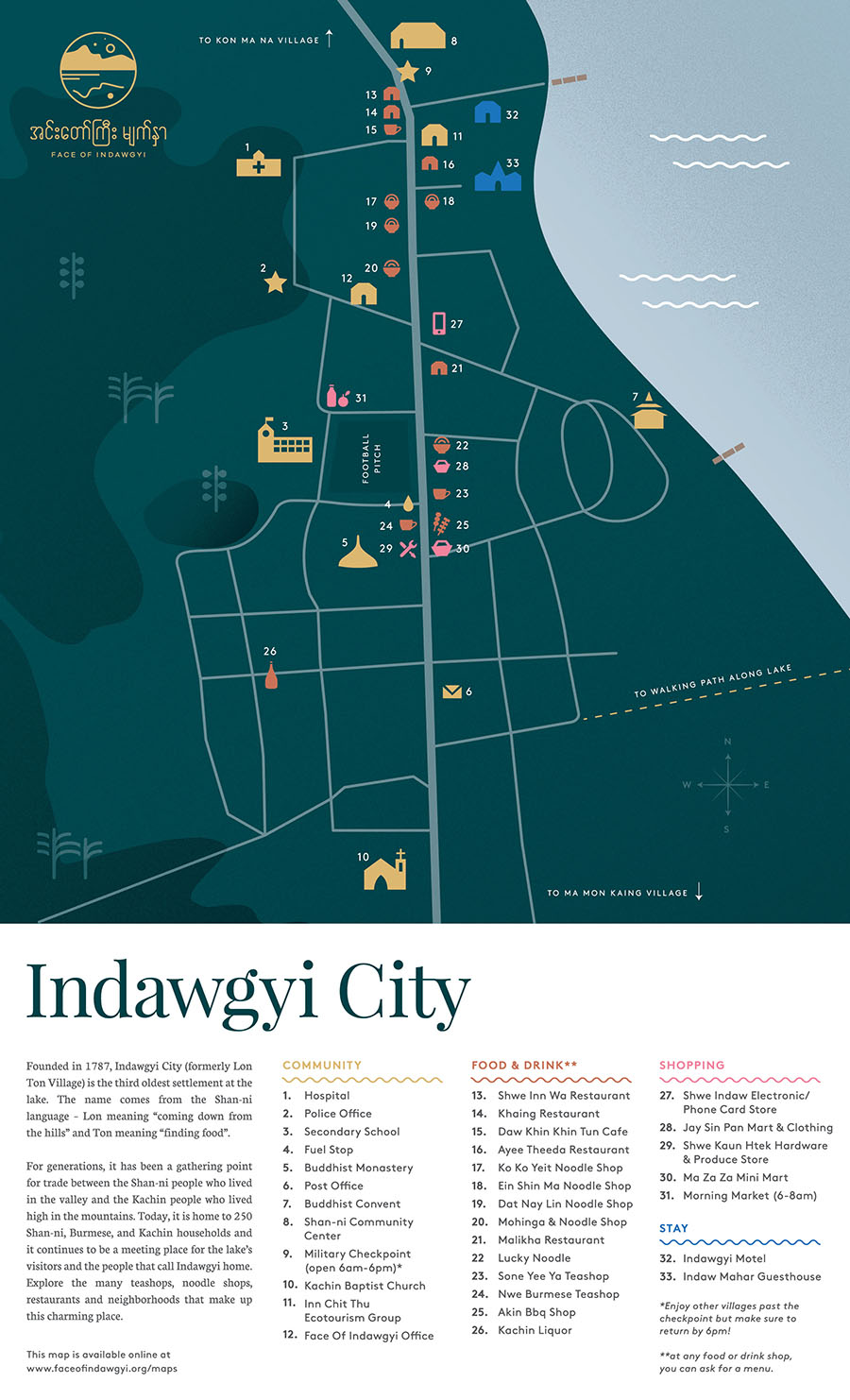

Face of Indawgyi has created a map of Lon Ton that includes useful information on where to eat, lake paths, shops and viewpoints. It has created multilingual menus for restaurants where travelers might eat. What’s more, the wide range of activities can be prearranged on the Face of Indawgyi website, including those already mentioned plus a visit to a traditional Shan-ni fabric weaving workshop, a local alcohol-making business and Shan-ni cuisine cooking classes.

Cash generated through tourism activities they organize goes straight into the hands of the locals providing the service. All other funds go into furthering the project’s reach around the lake.

“What sets [Indawgyi] apart from other destinations in Myanmar is that it hasn’t been overdeveloped. In fact, it’s barely developed at all. There’s still a unique identity,” said Compton.

As Inle Lake struggles with the waste burden of a growing number of visitors and construction projects on its shores, Indawgyi has the opportunity to establish environmentally sound tourism practices before visitor numbers really start to grow.

As part of its environmental work, Face of Indawgyi runs an anti-littering campaign that involves signage and awareness-raising and the installation of trash bins around four villages and at Shwemyitzu Pagoda. The simple bins are made locally from recycled fishing nets and set a good precedent for the future.

Shan-ni cultural preservation

Something Face of Indawgyi is passionate about is preserving and documenting the local culture. The people living around Indawgyi are predominantly Shan-ni, or Tai Laeng in their own tongue, a subgroup of the Shan. Over decades of repression by the military junta and suffering the effects of conflict in the area between Kachin armed groups and the military, the Shan-ni culture is not as strong as it once was. Only a few elderly locals and monks can speak the language, though a number of classes for youth have been started. Face of Indawgyi has been creating a Shan-ni oral archive and video documentation of the language and researched and recorded the unique oral histories of three villages on the lake.

Biodiversity at Southeast Asia’s third-largest lake

Indawgyi Lake Wildlife Sanctuary was established by the Myanmar government in 1999 and listed as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 2017. Of its 73,600 hectares, the lake covers 12,000. Species in the sanctuary include 10 globally threatened bird species, the endemic Burmese peacock turtle and a number of endemic fish species. However, the lake’s health is threatened by nearby small-scale illegal gold mines and unmanaged waste from the huge number of pilgrims who come for the annual Shwemyitzu Pagoda festival.

Blueprints for a guesthouse with positive social impact

Government numbers show foreign visitors to Indawgyi remain below 1,000 per year. It’s not easy to get here — the fastest way to reach Lon Ton from Yangon is to fly to Myitkyina and hire a car for the four-hour trip to the village. Many travelers make their way here on a long train or bus journey north from Mandalay, stopping off at Katha and Bamaw.

What will make the journey more worthwhile, however, is a better quality of accommodation, and Face of Indawgyi is onto that. After a complex yearlong bureaucratic process to lease the land, it has begun making plans for a 10-room guesthouse on the sloping site right at the lake’s edge that it hopes to open in March 2020. Set to be the “cornerstone of Face of Indawgyi,” it will incorporate a hotel training center funded by Luxdev and a community event space.

Face of Indawgyi’s projects are already wide-reaching and ambitious, but with a long list of plans for the future and ventures in the pipeline, this social enterprise holds lots of potential for genuine, long-lasting positive impacts on the community and environment of Indawgyi Lake.

As Compton said, “We have lofty goals, but figuring out concrete and measurable things we can do at this early stage sets the foundation for great things later on.”