With the coordinated strategy of the resistance forces spreading across the country, the degree of joint planning that preceded the launch of Operation 1027 has become visible in both the comprehensive nature of the nationwide strategy and the diversity of the opposition armed forces deployed in the various theaters of attack, as was described in the first part of this two-part series. After a two-and-a-half-year standoff between the junta’s military and those fighting for a new democratic federal government free of military control, the whole structure of the conflict seems to have shifted suddenly to incorporate a powerful array of ethnic armed forces that previously had not openly declared themselves to be on one side or the other of the anti-coup movement. The junta military now finds itself facing a more formidable enemy, even as the strength, capacity, and morale of its own forces have diminished severely. And the opposition forces find themselves consolidating victories against the military across the country much more rapidly than they expected. The generals in Naypyitaw are clearly fumbling to find an effective defense against the formidable new threat facing them.

For their part, the key stakeholders in the resistance movement must also adjust to the reality of their newfound prowess on the battlefield thanks to coordination with a number of powerful armed groups that have not previously participated in political discussions about the future of federal democracy in the country. With events on the battlefield unfolding rapidly and taking a dramatic toll on the weakening military forces, the political development of negotiating a settlement to the post-coup conflict that aligns with popular expectations for a federal democracy, free of military control, becomes increasingly urgent. The coordination and inter-ethnic unity that have been achieved on the battlefield need to be effectively translated into an alignment of political goals for the future federal democratic union.

A ‘wave by wave’ strategy

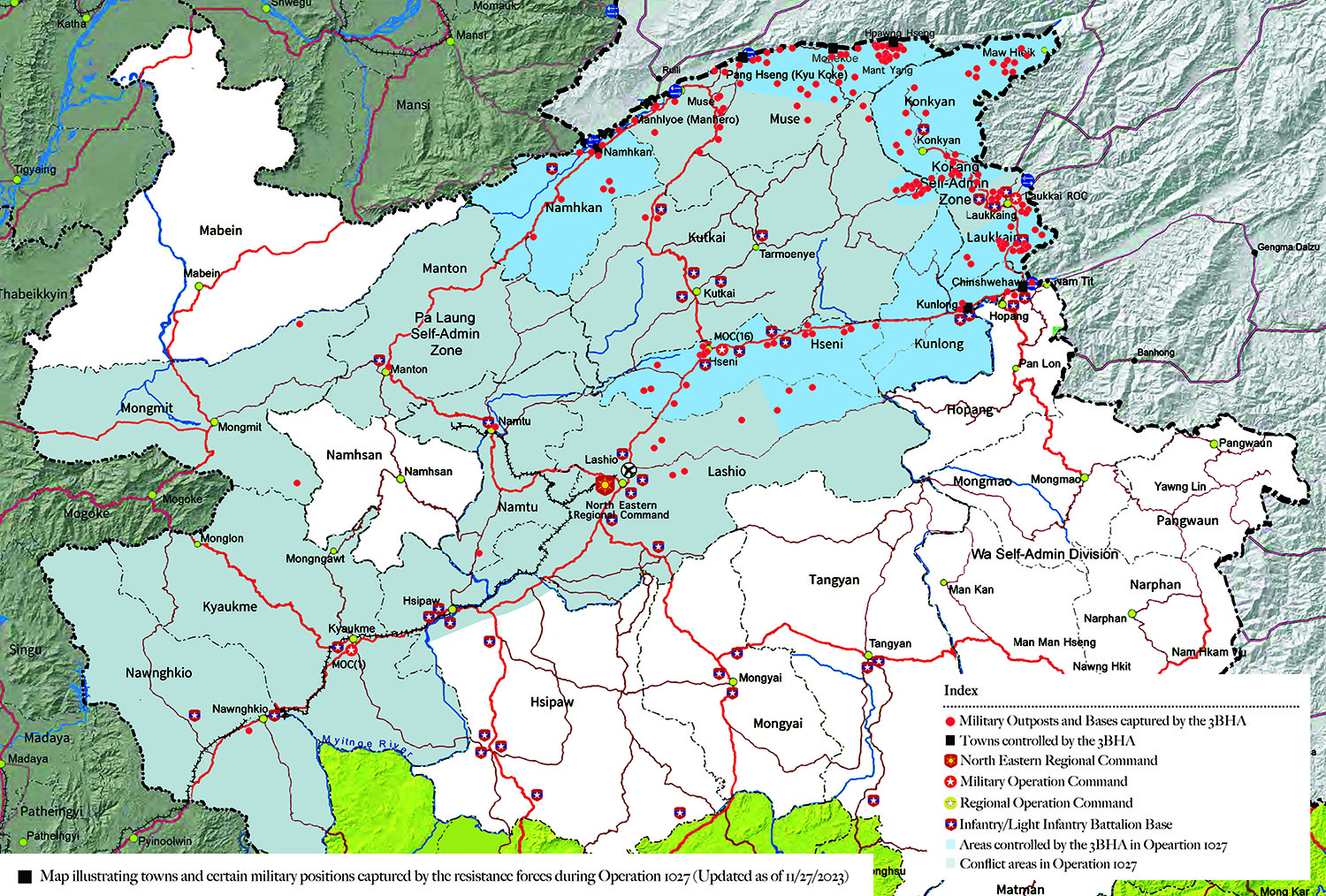

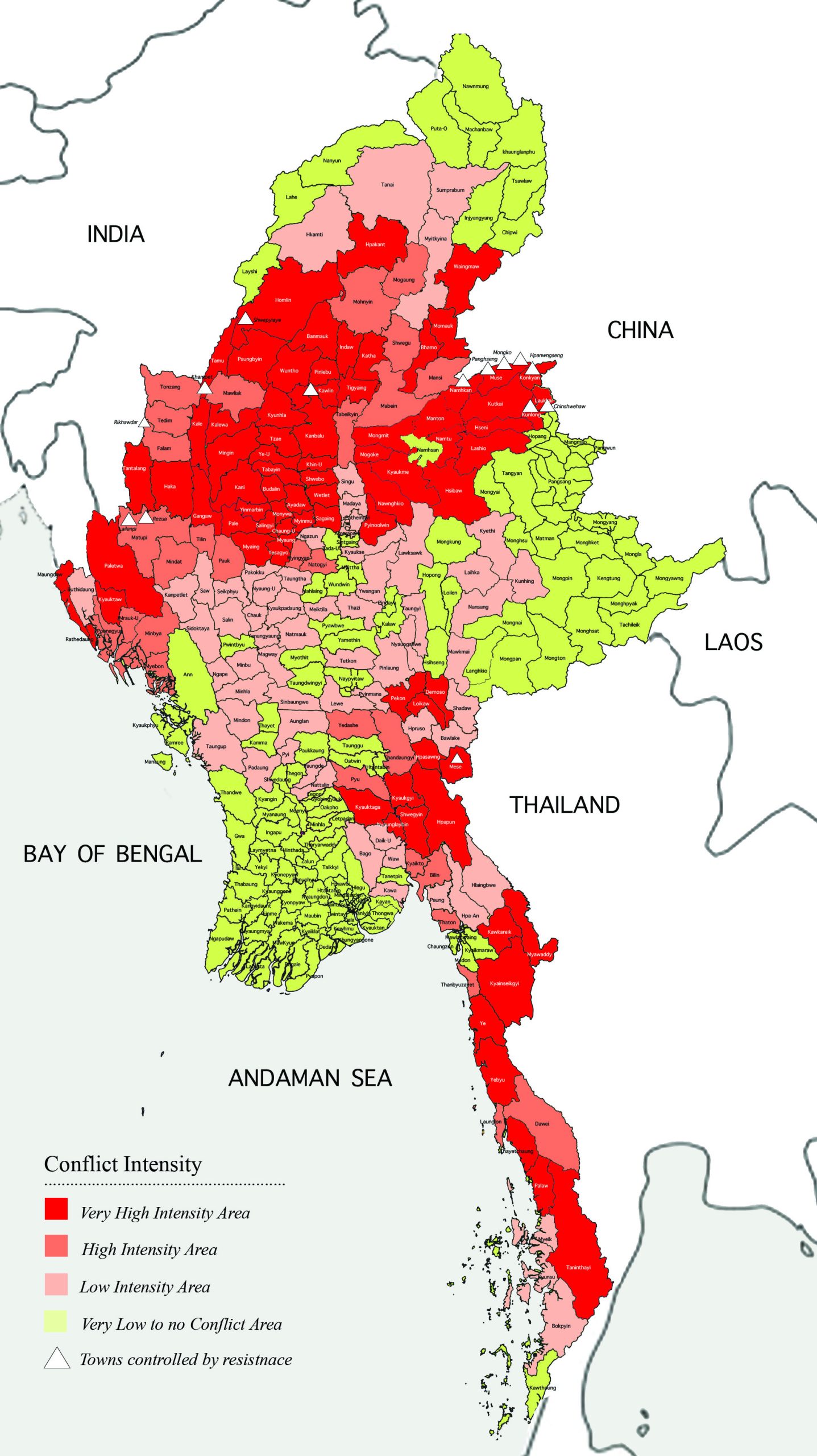

Following the commencement of Operation 1027, the resistance forces released a video conveying a message that operations would unfold wave by wave against the Myanmar military; that Operation 1027 was not an end but just the initial phase of the first wave. The idea of executing this strategy in waves over time suggests that the ongoing coordinated offensives are not unrealistically targeting the immediate collapse of the military and the seizure of many towns at once. The strategic objective of the first wave was to launch simultaneous and coordinated attacks to cause military troops to disperse over many conflict hotspots, gradually depleting the resources and strength of the State Administration Council (SAC), as the junta calls itself, while the resistance forces penetrate strategically important areas, gain control of key towns and routes, and solidify supply lines and base areas. However, the rapid successes of Operation 1027 and the subsequent loss of many bases and towns by the military apparently surprised even the battle planners within the resistance. They are now gradually advancing in the first wave, capturing more military bases of strategic significance and solidifying their gains by preparing a strong defense.

As they assess their progress, the resistance forces are positioning themselves strategically to launch the second wave. In this next phase, we are likely to see greater focus on expanding resistance operations into urban areas and securing important locations in Myanmar’s heartland, as well as key ethnic strongholds. The successes of the first wave show that, in contrast with the ebb and flow that marked resistance gains during the previous two-and-a-half years, resistance forces continue to move forward with a determination and growing strength that will severely challenge the waning strength of the Myanmar military.

Declining military strength

The unexpected success of Operation 1027 is due in large part to the serious decline in military manpower and capability over the past two years of endless multi-front conflict. High rates of desertions, defections and casualties, and a dramatic decline in morale among ground troops, have taken a heavy toll on the once powerful Myanmar army. The overstretched military is finding it impossible to cope adequately with coordinated simultaneous attacks by resistance forces in a variety of theaters, particularly when demoralized troops are preemptively surrendering or defecting to the resistance. The recent losses of high-ranking combat officers and a jet fighter to resistance attacks have taken a psychological toll on the military. And responding with air strikes and artillery attacks is only minimally effective when confronted with simultaneous opposition attacks in far-flung theaters of conflict. Military leaders consistently make hollow claims of retaking lost positions in Karen, Kachin, Karenni (Kayah), Chin and other areas, which prove false and result instead in further losses of military bases.

On Nov. 8, 13 days into Operation 1027, the junta leadership convened a rare meeting of the National Defense and Security Council and announced plans for a military counteroffensive to reclaim the lost towns and military bases in northern Shan State. But, after a month of Operation 1027, the military’s counteroffensives appear to be ineffective. With the recent escalation of fighting in Rakhine, Karenni, Sagaing and Bago, military planners dare not risk redeployment of troops from these areas to reinforce operations elsewhere. Although the military has deployed limited reinforcements by extracting some troops from battalions in other theaters for counteroffensives, aerial reinforcement is severely constrained, and ground reinforcement faces challenges over lengthy supply lines vulnerable to resistance attack and blocked by resistance forces and destroyed bridges.

The military has, for example, spent significant resources attacking resistance forces at the gateway to the Mandalay-Lashio highway in Nawnghkio and Kyaukme, which provides the access necessary to resupply troops in northern Shan State. Despite some advancement by the reinforcement troops as resistance forces withdrew to a nearby location after approximately 20 days of intense fighting, military troops encountered another significant obstacle in Hsipaw and their back line remains highly vulnerable to attacks by the withdrawn resistance troops. For over a month, the military’s counteroffensives have been sluggish, with a significant portion of its reinforcement troops still ensnared along their route.

In its current counteroffensive, the military could employ a barrage of air strikes and artillery attacks to destroy towns captured by the resistance and to target the civilian population, aiming to discourage them from residing in these areas. At best, they would only be able to create a semblance of control by re-establishing some military outposts in areas they have demolished with massive air and artillery strikes. But the past two-and-a-half years have demonstrated that such tactics are of little military value without sufficient ground troops. Instead, these tactics have encouraged the resistance, boosting their confidence and contributing to their growth in strength and the acquisition of more strongholds.

The effectiveness of the military counteroffensive will have a direct impact on resistance planning for subsequent phases. If the military response proves weak and ineffectual, it will have unimaginable consequences for the military, and resistance forces are likely to advance more forcefully and speed up their collective operations.

Military equilibrium shifts toward the resistance

Operation 1027 has brought three interrelated changes in the dynamics of conflict in Myanmar: a shift in tactics, a pattern of coordination, and changes in the military equilibrium. The shift in tactics occurred within the resistance, which predominantly consists of ethnic armed groups that have been heavily reliant on guerrilla tactics in their prolonged wars with a powerful standing army. They and their PDF partners have consistently employed guerrilla warfare, including ambushes, mine attacks, hit-and-run maneuvers, and acts of sabotage, during their participation in the anti-coup resistance. Because of a limited supply of arms and ammunition, the resistance forces have been struggling to take fortified military bases, towns and strategic routes. In Operation 1027, the Brotherhood Alliance, amply supplied with arms and ammunition, deviated from their traditional guerrilla tactics by capturing military bases and towns. While resistance forces in other areas do not yet have the capacity for this, the success of Operation 1027 has boosted their morale by demonstrating the increasing weakness of the junta military. The seizures of Kawlin, Khampet and Shwepyiaye in Sagaing Region, and Rihkhawdar, Lailenpi and Rezua in Chin State are prime examples, and may foreshadow resistance moves from rural hideouts to urban areas in the near future.

The second change can be seen in the new pattern of coordination among the diverse resistance forces, a clear divergence from the past. Key resistance actors, including the National Unity Government (NUG) and the Brotherhood Alliance, have come to prioritize achieving visible success through coordination on the battlefield rather than the slow-paced, time-consuming comprehensive political negotiations by which international observers have been measuring resistance unity. The armed forces in the resistance all recognize that the Myanmar military is the obstacle to achieving their varied objectives, so they have a shared interest in fighting that common enemy. Brigadier General Tar Bone Kyaw, the general secretary of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA, a member of the Brotherhood Alliance), stated that “the objective of all our groups is to root out the military dictatorship in Myanmar by ramping up the military momentum, and to proceed toward the goal of the Spring Revolution.” While detailed holistic negotiations on the form of a future state still lie in the future, the success of the current coordination on the battlefield may serve to build the mutual trust that will be essential to achieving political agreement in the end.

The current state of the conflict is very fluid, with the coordinated resistance strategy still at an early stage, so the outcome is as yet unpredictable. From the start of the armed resistance movement, the military’s overwhelming air power and heavy weaponry have managed to create an image of invincibility despite its growing weakness in manpower, morale and pubic support. The resistance forces had been primarily in a defensive posture, relying predominantly on guerrilla tactics. With the sudden emergence of a coordinated resistance force shifting to the offensive on many fronts, there is no question that Operation 1027 and its impact on the pace of conflict throughout the country has achieved a discernible shift in the military equilibrium in favor of the resistance forces. The military has been compelled to go on the defensive in order to prevent further loss of bases, manpower and supplies. If the resistance forces can sustain their coordinated strategy to advance on the military from various directions, they will be able to keep the equilibrium on their side.

Building peace will be a heavy lift

The current rapid pace of military progress highlights the urgent need for key resistance stakeholders to expedite the political process and align it with these military advancements. Military coordination and victories on the battlefield alone won’t be sufficient to build a peaceful federal democratic union in Myanmar. Furthermore, military coordination on the ground would be shaky and precarious without strong political commitments from key resistance actors. The sense of common purpose and trust building on the battlefield need to be carried into genuine political negotiations for the future state.

It will first be necessary for the resistance to sustain and enhance the current military coordination. In tandem with the military progress, they also need to coalesce around a negotiating strategy when the time comes and to prepare administration of interim arrangements for restoring the economy and the health and education systems, and providing other forms of socio-economic support required to stabilize a traumatized population. Life cannot wait for completion of the arduous process that lies ahead to reach agreement on a new constitution with the goal of democratic federalism.

In light of recent developments, the international community needs to recognize the current evolving military equilibrium in Myanmar. They should also place confidence in the locally developed process of coordination and cooperation among the resistance actors. Despite its slow progress and the remaining areas in need of improvement, this process has achieved more common ground and cooperation among the many ethnicities in the country than was heretofore thought possible, and it remains the sole viable path out of the current quagmire in the country. The international community has no alternative but to support the existing process within the resistance movement for the stability and peace of Myanmar.

Ye Myo Hein is a global fellow at the Wilson Center based in Washington DC. The views expressed here are his own and may not reflect those of the center or the US government.