On Aug. 29, 2023, Daw Zin Mar Aung, the National Unity Government (NUG)’s foreign minister, held a virtual press conference addressing several points; one of which is its plan to dedicate more resources to diplomatic relations with neighboring countries including Thailand. As Thailand is now set to have a new government sworn in by Sept. 8, I posit that efforts by the NUG to engage with the incoming Thai government, in both a formal and informal capacity, require internal cooperation from relevant stakeholders. Moreover, it needs to develop a holistic understanding of Thailand’s interests and stakes in Myanmar.

With 2,401 km of shared border, Thailand faces a myriad of opportunities and challenges when it comes to navigating relations with Myanmar. On one hand, border trade through the six border stations has nurtured both countries’ markets with various types of products from rice, coal and fisheries to labor. The Institute for Strategy and Policy-Myanmar (ISP-Myanmar) reported that this economic-driven relationship between Thailand and Myanmar has persisted, and even flourished, since the 2021 coup wherein three out of six border trade stations have experienced an increase in trade, amounting to over 66 percent of all border trade value.

On the other hand, it means that Thailand must constantly deal with different actors, particularly the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), as de facto territorial controllers along the border, to safeguard economic interests and security. After the coup, many of these border EAOs may not share the same views and affinities (e.g., pro-SAC, anti-SAC, neutralists, pro-China, etc.), making it more difficult for Thailand to navigate the already complex and precarious sociopolitical landscape of Myanmar in furtherance of its own interests. Apart from that, it is especially important to note about the depth and breadth of Thailand’s stake in Myanmar’s energy sector since three out of the four major offshore oil and gas fields in Myanmar that export to Thailand are regulated by the SAC-controlled Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE).

Although a report from Earthrights has debunked Thailand’s claim of energy reliance on Myanmar, it is also possible that the symbiotic tie between the Myanmar and Thai juntas through state-owned enterprises is one of the reasons that underlies such a claim. Specifically, PTT Exploration and Production (PTTEP) is a subsidiary of the Thai state-owned PTT Public Company Limited; and since the 2014 coup in Thailand, the number of military personnel in state-owned enterprises, including PTT and its subsidiaries, have doubled. Since PTTEP operates two gas pipelines in Myanmar, Yadana and Zawtika, it effectively bankrolls the juntas of both sides in the process.

Pulling out from the projects at the appeal of the NUG, other Myanmar activist groups or even the international community, would mean an income loss for Thailand and for some military generals. Through this logic, it necessitates that Thailand maintain good relations with the SAC not only for energy, but also for the profitability of some elites. All in all, then, the post-coup situation makes it increasingly challenging for Thailand to achieve a balancing act and to keep optimal relations in a multistakeholder situation in which all relevant stakeholders need to be kept reasonably satisfied.

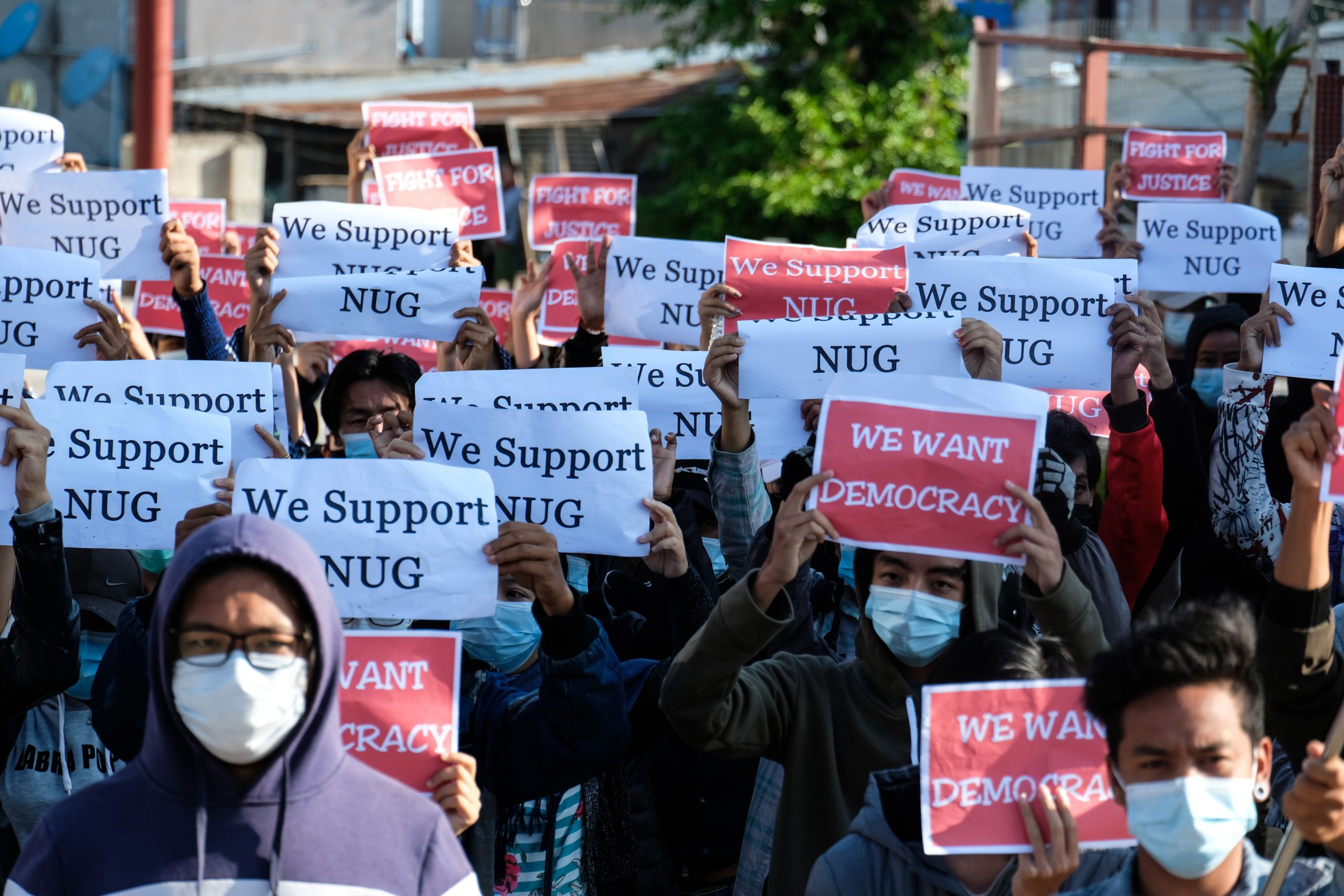

At the most rational level, Thailand generally prefers stability in Myanmar, which can ensure both economic productivity and border security—both of which have been sufficiently fulfilled by working with Tatmadaw forces and border EAOs prior to the 2021 coup. This begs the question of the position of the NUG as a new actor in this existing equilibrium. Apart from its oft-cited legitimacy from the 2020 election, the NUG has been described as “unconvincing” by many sources as the potential leader of the future Myanmar, partly due to its lack of territorial control. From a political communication perspective, the NUG needs to remedy this lukewarm perception from both international and domestic audiences should it want to continue to be a part of the new Myanmar.

Chiefly, the NUG needs to reconsider its strategy on Thailand since the naming-and-shaming tactic, which eventually turned into a threat of a lawsuit, that it wielded in regards to PTTEP’s investments in Myanmar, has proven to be futile. As mentioned, energy security is a sensitive and complicated issue with great implications for Thailand’s interests. Now that the Pheu Thai Party has formed a coalition government with the pro-establishment and former junta parties, any added pressure on the energy issue will be counterproductive. The NUG’s objective for future engagements should be to foster amity with Thailand, not woes.

In a related issue, while the NUG is planning to pivot to requesting more humanitarian aid, it will need to better articulate the form of such requests to Thailand. At this stage, humanitarian assistance to neighboring countries is not a priority for most Thais amidst the domestic sociopolitical struggles. Combining that with a long history of indoctrination that cultivates resentment and adversary among the Thais towards the Burmese through education, it will be hard for any incoming government to produce new and positive policies on Myanmar. Consequently, it is important for Myanmar stakeholders, including the NUG, to identify and proffer alternative policy entry points that allow for quid-pro-quo scenarios. With the Pheu Thai Party leading the coalition, one can expect a more capitalistic approach to Myanmar without exacerbating the crisis. So, the integration of post-coup Myanmar migrants into the Thai market to contribute to the economy through revenue-generating schemes or transboundary healthcare provisions might be more appealing to them than the bare basis of human rights protection. More importantly, those policy proposals should be data-driven and evidence-based for them to be justifiable to broader Thai electorates; and hence, executable.

To leverage, then, any engagement initiatives from the NUG cannot be done without coordination with the EAOs, which have decades of relations with Thailand as border partners. To name a few, the Karen National Union (KNU) and Karenni Nationalities Progressive Party (KNPP)—both of which have extensive governance and service provision systems to deliver public services to communities along the border and have been lifelines for aid delivery for years—and their emerging entities in a future Federal Union. Coordination and cooperation from these entities, prima facie and at policy-level, will be crucial to the NUG’s effective engagement with Thailand.

Moreover, future engagements should include a clear roadmap for the future of Myanmar. Since the 2021 coup, “federal democracy” and its variants have reemerged as the prime buzzwords for anti-Tatmadaw forces. However, it is observed with caution that some stakeholders may not share the same purviews about how federalism should be achieved. Without a clear discussion on how different expectations will be addressed and reconciled in the process, it will prove to be challenging not only for communication with international audiences but also to the very prospect of nation building down the road. Therefore, future engagements should include not only the goal of federal democracy, but also the plan on how such a goal can be realized. As such, it is necessary for the NUG, a Bamar-dominated apparatus, to recultivate trust among the ethnic groups and show that it can emerge as a true interlocutor to facilitate a nation building dialogue. This includes the reopening of space for difficult discussions such as state rights and autonomy, representation, and distribution of resources, which may even go beyond what is in the draft Federal Democracy Charter.

For international audiences, delivery of consolidated talking points though a unified front, obtained via domestic cooptation, will help tremendously in terms of boosting credibility. These points on coordination for leverage credibility should harken to the bigger reality-check for the NUG that it is not a government with actual governing power or authority in Myanmar’s terrain. In fact, it is, among many others, a revolutionary force. So, it is necessary to conduct itself as such and extend the olive branch to other groups, affording them equal voice and influence in the process.

Dr. Surachanee Sriyai is a lecturer and digital governance track lead at the School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University. Her research interests include digital politics, political communication, comparative politics, and democratization.