Bomb blasts not only in major cities like Yangon, Mandalay and Naypyitaw, but also in smaller upcountry towns, ambushes on army convoys, gun battles in Magwe and Sagaing regions, and, across the country, assassinations of suspected military informants. While it is too early to describe the violence that has broken out in the Myanmar heartland since the Feb. 1 coup as a full-scale civil war, the military, known as the Tatmadaw, has for the first time in decades had to fight armed rebels in areas far away from the country’s traditional trouble spots in the ethnic-minority-inhabited frontiers. It is an entirely new kind of conflict that the Tatmadaw is not used to fighting and, therefore, incapable of containing. It is, for instance, doubtful whether its intended attacks on the rebel forces—which amount to indiscriminate firing into inhabited areas because the soldiers are unable to locate them—will have any effect other than further alienating and radicalizing a population that previously only demonstrated peacefully against the coup.

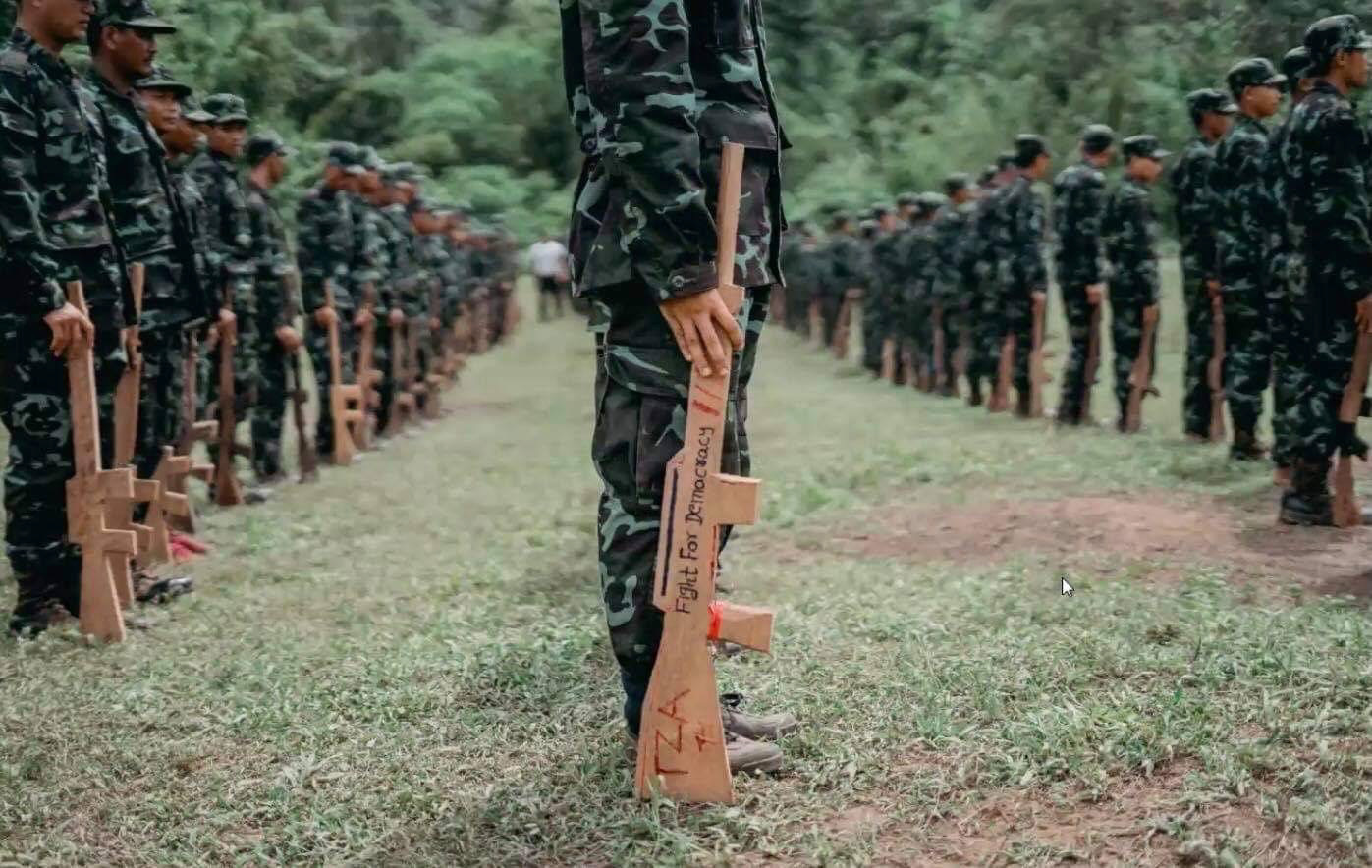

Myanmar’s new kind of armed conflict differs also in many other respects from the old wars against ethnic rebels in the border areas, as well as the fighting in the heartland in the years immediately after independence from Britain in 1948. Myanmar’s ethnic insurgents have always been organized along strict military lines, which makes them unique in a global perspective. Unlike rebels in other countries, they are dressed in distinct uniforms with insignia showing their ranks. Myanmar’s ethnic rebels look more like regular armies and control and administer areas, and have camps complete with barracks, parade grounds and makeshift office buildings.

The Burman militants who after independence resorted to armed struggle against central authorities were not that well-organized. But they also established huge base areas which they governed and from there launched attacks on government positions. That applied to smaller groups like militants from the People’s Volunteer Organization, a paramilitary force formed by General Aung San after World War II that rebelled after independence, and various bands of mutineers from the Tatmadaw—but mainly to the once powerful Communist Party of Burma (CPB).

Communist strongholds attacked

Soon after the outbreak of the civil war in 1948—and at that time, it was an all-out civil war—the CPB established strongholds in the Pegu Yoma mountains north of Yangon, in the Irrawaddy Delta, the Arakan Yoma, Tenasserim (now Tanintharyi), and upper Sagaing Division (now region). It was also active in and around Pyinmana, where the party organized farmers in struggles and strikes against landlords and moneylenders. At one stage, the cabinet of the then prime minister, U Nu, was referred to as “the Yangon government” because it did not control much more than the then capital itself.

Karen rebels battled in the eastern mountains and in the Irrawaddy Delta for independence. In northern Arakan (now Rakhine State), Muslim rebels known as mujaheeds fought for accession to Pakistan (Bangladesh was then the eastern part of Pakistan.) Smaller groups of Karenni and Mon rebels had their own armed bands in areas near the Thai border. Nationalist Chinese, or Kuomintang, forces that had been defeated by the communists in the Chinese civil war, had bases in northern and eastern Shan State from where they tried, unsuccessfully, to re-enter China and foment an uprising against Mao Zedong’s government. In the late 1950s, a rebellion broke out among the Shan and, in the early 1960s, the Kachin organized one of the strongest ethnic resistance armies in Myanmar.

While the Tatmadaw never managed to defeat the ethnic rebels in the border areas, it was more successful fighting the CPB. By the late 1950s, the CPB’s forces had been more or less contained to the Pegu Yoma with smaller units holding out in the mountains of northwestern Arakan, the jungles of Tenasserim, and the Pinlebu area in upper Sagaing. The Kuomintang, meanwhile, had been driven across the border to Thailand and no longer poses any serious threat to national security. Myanmar’s communist insurgency would also have been over—had it not been for the People’s Republic of China.

In 1968, CPB soldiers, of whom many were Chinese Red Guard volunteers accompanied by Burman political commissars, poured across the border with China into northern Shan State. They soon recruited local tribesmen to fight for them and, within a couple of years, a new and very different CPB base area had been established. It encompassed more than 20,000 square kilometers of territory adjacent to China, stretching from Panghsai and Mong Ko in northernmost Shan State, to Kokang and the Wa Hills, and down to the mountains north of Kengtung. The “new” CPB had its own administration in those areas—and was much better armed than the “old” CPB. During the decade 1968-1978, China poured in more arms, ammunition and other supplies to the CPB than to any other foreign communist resistance movement outside Indochina.

But the CPB never intended to stay in the wild mountains on the Chinese frontier. The plan was to push down to the Pegu Yoma and other strongholds in central Myanmar and, eventually, take over Yangon. The Tatmadaw realized that, and also concluded that it would not be able to defeat the new, well-equipped forces. Hence, the Tatmadaw decided to contain the CPB in the northeast — and to wipe out what remained of the CPB in central Myanmar. In that way, the CPB would never be able to seize power.

That strategy was clever and it worked. The Irrawaddy Delta region and some smaller strongholds were “pacified” in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A massive offensive was then launched against the Pegu Yoma. The CPB camps there were overrun in 1975 and the civilian population in and around the mountain range was resettled in other parts of central Myanmar. After that, there was no more fighting in the Myanmar heartland against the CPB. Karen rebels who had also been active in the Pegu Yoma and the Irrawaddy Delta lost their bases there as well, and the survivors retreated to the Thai border.

It was only in 1991 that the Karen National Union (KNU) managed to send some troops to re-enter a Karen-inhabited area in the Irrawaddy Delta. Unexpectedly for the Tatmadaw, Karen rebels, who had come from the Thai border, were seen digging trenches and stockpiling guns in the Bogalay area only some 140 km southwest of Yangon. The Tatmadaw responded with fury using newly acquired Chinese aircraft and gunboats. The then commander of the Tatmadaw’s infantry, General Than Shwe, led the campaign, which was codenamed Operation Storm and led to the KNU troops in the area being eliminated—but at a heavy price for the civilian population, who suffered badly during the onslaught on the rebels. Villages were bombed and, among those killed, most were ordinary villagers, not insurgents.

Ceasefire with the Wa

After the fall of the Pegu Yoma, insignificant CPB units managed to hold out in northern Arakan and in Tenasserim, but the party had become isolated in its base area in the northeast, where it did not belong and never had any intention of staying. That, in turn, led to a mutiny within the non-Burman, mainly Wa but also Kokang, rank-and-file of the CPB’s army in 1989. The old CPB leadership was driven into exile in China while its former forces were reorganized into ethnic armies, the strongest of which became the United Wa State Army (UWSA). But rather than fighting, it entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Tatmadaw soon after the mutiny.

Since then, rather curiously, the UWSA has become stronger and better equipped than the CPB ever was—and its guns and other supplies have been obtained from China. While the UWSA is not doing any fighting on its own, it has shared some of its weaponry with other ethnic armies such as the Shan State Army of the Shan State Progress Party, the Palaung Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the Kokang-based Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and, to a lesser extent, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA).

Those armies are fighting the Tatmadaw, but the powerful Arakan Army (AA), which has also benefited from UWSA arms supplies, has distanced itself from all other resistance armies in Myanmar. The AA says it wants to regain the independence the old Arakan kingdom lost to the Burman kings when they occupied the area in 1785. With that aim in mind, the AA has not established any liberated areas but, instead, built up a parallel administration in Rakhine State.

That, briefly, was the situation until the Feb. 1 coup. The new Burman resistance fighters are supposed to be organized into a loose alliance called the People’s Defense Force (PDF). That umbrella organization is considered the armed wing of the National Unity Government (NUG), which was set up by ousted MPs and other politicians after the Tatmadaw staged its coup and formed a junta called the State Administration Council (SAC). But it is uncertain how much coordination there is between the different PDFs and, in addition to those, there is an abundance of other local resistance forces that operate independently. But all in all, the anti-SAC resistance is active mainly in Magwe, Sagaing, Ayeyarwady, Mandalay and Tanintharyi regions, where there has been no heavy fighting for decades. Fighting has also flared up in Chin and Kayah (Karenni) states, ethnic areas which before the coup were the scene of only low-intensity conflicts.

PDF/ethnic alliance

The PDFs in the far north are allied with the KIA, whose soldiers have even accompanied groups of Burman resistance fighters in raids outside the boundaries of Kachin State. By doing so, the KIA is hoping to draw Tatmadaw units away from its besieged bases in Kachin State, a military strategy that seems to have had the desired effect. The Tatmadaw now appears to be gearing up for major offensives in Magwe Region and Chin State, not in the far north.

The outcome of the fight against the PDF is uncertain, as the Tatmadaw cannot employ the same tactics as it did against the CPB. The new-era rebels, unlike the CPB in central Myanmar in the old days, do not have any “liberated areas” with camps that can be overrun. And they cannot be contained in the border areas because those are controlled by the KIA and other ethnic armies. In rural areas, it is a hit-and-run game while, in the towns, Myanmar is for the first time in history facing urban guerrillas—and the Tatmadaw has zero experience of that kind of warfare.

It is also a question of what kind of resources the Tatmadaw can throw into battling this new kind resistance. An offensive in one part of the country could lead to more rebel activity, ethnic as well as Burman, in other states and regions. The Tatmadaw will be stretched thin on many battlefronts at a time when the morale of its troops is already low. Constant ambushes and bomb attacks along roads which only a year ago were considered safe have taken their toll on the soldiers’ willingness to fight—and that applies to all corners of the country. According to local, non-partisan civil organization workers, Tatmadaw units in Karen State have even resorted to reporting phantom battles to their high command in Naypyitaw. They claim that they have captured Karen rebel camps and outposts when no such attacks occurred, and to have been engaged in battles that never took place.

It is impossible to say what the extremely complex situation that the coup has caused will lead to. In the worst-case scenario, it could cause a fragmentation of Myanmar with no one able to hold the country reasonably well together. Dissent within the ranks of the Tatmadaw could also led to coups or coup attempts with extremely uncertain outcomes, even a repeat of the mutinies and chaos that prevailed in the wake of independence in 1948. But gone is the cautious optimism that many, falsely it turned out, felt after the Tatmadaw decided to open up the country in 2011. False hopes on the part of the Tatmadaw because it had not expected the massive rebirth of the National League for Democracy—and a development that was misinterpreted by mostly foreign pundits who seemed to believe that the generals had gone through some democratic awakening experience. In the end, it was inevitable that the Tatmadaw would intervene and try to reassert power. We are now experiencing the disastrous consequences of that fateful decision.

Bertil Lintner is a Swedish journalist, author and strategic consultant who has been writing about Asia for nearly four decades.

You may also like these stories:

UN Ambassador Saga Spotlights China’s Cautious Approach to Myanmar

Myanmar Junta Steps Up Arrests of Striking Civil Servants

US Sanctions Pose Huge Risks for Myanmar Businesses