The Washington Post recently noticed that “Myanmar’s Junta May be on the Verge of ‘Collapse,’” due to the military success of the Three Brotherhood Alliance in the north, and the political legitimacy of the NUG. The Washington Post then described a multi-party conflict that is potentially resulting in the mass defection of the junta’s soldiers.

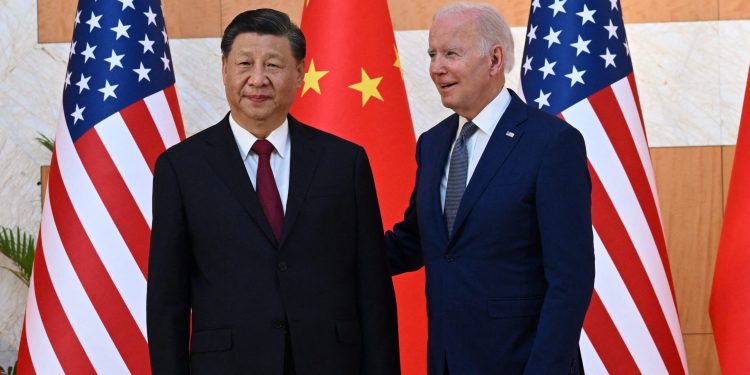

The Post’s apparent solution? Have Washington insert itself into the situation by having the US State Department “promote and prepare the National Unity Government,” and send the junta packing to somewhere else, though where is not clear. The Three Brotherhood Alliance is then dismissed because, unlike the NUG, it is aligned with China. America would then presumably bring the NUG’s new Myanmar into a new Washington-led consensus, which means applying USAID policies via US contractors, opposition to Chinese influence in Myanmar, and American-style democracy. All in all, such a solution is not that objectionable in the short term, mainly because the junta is eliminated. But the bigger problem is that at the end of the day, China is still the most important foreign player in any peace process, a fact that American policy in Myanmar still ignores. Afficionados of international relations know that there is a Cold War between the United States and China focused on Taiwan, the South China Sea, trade issues, and mutual spying. Myanmar is peripheral to this rivalry but still a pawn. China wants a gateway to the Indian Ocean via rail and ports, but it also does not want its neighbor Myanmar swept into the United States’ orbit. The US wants to preserve economic advantages for its Thai ally to conduct business, wage America’s ‘War on Drugs,’ establish democracy, but more importantly, frustrate China’s plans in Myanmar.

I spy, we spy, they spy

The spycraft going into the rivalry between China and the US in Myanmar is not new, extending across Taiwan, the South China Sea, Asia and beyond. Since independence, Myanmar has been at the periphery of competition between China and the US. Each has sponsored small armies of rebels since the 1950s, while also assisting the military governments with military assistance to sustain the massive Tatmadaw (Myanmar military).

Which raises a question for the Washington Post (and the US State Department). Might a post-junta government be a good place to initiate a cooperative détente in which the two great powers, China and the US, work together to establish a legitimate Myanmar government? Imagine a world where Myanmar’s government negotiated independently of great power politics for economic and infrastructure deals with China, and public health, and democratic development sponsored by the United States. Perhaps even the US and China could work together to build high-quality infrastructure, eradicate the drug trade and close criminal scam operations. But this will only happen after peace is restored, and the hated Tatmadaw, which exists in the interstitial spaces between Chinese and American military policy, demobilized. Maybe with the recent military and political victories by the NUG and others, this might be possible soon.

What could be given up by the great powers in a post-junta world?

But for a détente to begin in Myanmar, China and America need to give up the tools they use to deal with each other.

The Americans need to limit their aid to legitimate programs in things like democracy and governance promotion, education, and health, and cease the clandestine support in the name of “security.” This also means they cannot redact the names of the partner agencies to which they supplied over $100 million in 2023. More to the point, the Americans need to stop opposing Chinese projects because they are Chinese, and instead look at the merits of each, and even evaluate joint sponsorships.

As for China, its embassies, companies, and sponsorships also hide clandestine involvement in Myanmar. But projects to construct ports, railroads, pipelines and dams to serve southern China have faltered in the context of broader policies of supplying both the military regime and the ethnic armed groups. Indeed, Chinese policy has resulted in strange statelets run by syndicates that victimize Chinese, Myanmar people and others, and that thrive in the chronic fighting between militias. Maybe China will eventually realize that this policy, while effective at keeping America out, is still ineffective as a way to develop a stable frontier.

Neither the US nor Chinese policies are successful in sponsoring a stable Myanmar. Instead, both great powers use Myanmar as a pseudo-battleground in their own quest for hegemony in the Pacific, and elsewhere.

What can the US and China and do that will help?

A post-coup Myanmar will not suddenly break out in a big group hug, and foreign aid from China, the United States, the EU, ASEAN, and others should reflect this. This is, in fact, normal after wars. The winds of hatred were cultivated by the Tatmadaw, the ethnic groups, and their sponsors from China, the US, and elsewhere for decades. These hatreds must be moderated enough for the demobilization of armies; resettlement of IDPs, refugees, and exiles; just negotiations for power-sharing and natural resources; and the establishment of an education system(s) which serve all. Such negotiations are made more difficult by the shady “all sides” military assistance provided by the Chinese and Americans.

Which brings up the need for détente – a mutual disengagement regarding the Cold War that China and America have engaged in over the decades in Myanmar. A new détente requires that China, the United States, and Thailand stop the “I Spy/James Bond” stuff, and demobilize their secret services in Myanmar. This is important because, in a post-junta world, the number of weapons arriving in Myanmar must slow if there is to be peace. As important, it would set a small example for the Tatmadaw, and the many militia left in Myanmar, that demobilization of the war machines is necessary and works. When the junta is defeated, the US and China will have a chance to “back off” from clandestine meddling and provide room for a new government which contains elements of the NUG, Brotherhood Alliance, KNU, KNDF, Rohingya, and others. This is best done without China and the US picking victors.

Demobilization of the Tatmadaw and détente between Myanmar groups

At the forefront of any détente within Myanmar is the demobilization of the massive Tatmadaw, and other military forces. Demobilization of the Tatmadaw will be difficult for any new government; even the NUG will be tempted by the allure of raw military power that taking over the Defense Ministry will bring. This will first be difficult because it requires a level of trust within Myanmar. Second it will be difficult because for demobilization to occur, China, the US, Thailand, and Russia all need to stop arming their proxies in Myanmar.

Demobilization of the militaries is a critical policy which will reassure the people of Myanmar, as well as neighbors. The presence of a large battle-tested Myanmar army, even one commanded by an NUG-Three Brotherhood Ministry of Defense, poses a threat to highlanders and Myanmar’s neighbors, especially Thailand, Laos, and Bangladesh. Demobilization will be difficult for the Tatmadaw’s soldiers who are well aware how much hatred they inspire among the people. Imagine a 22-year-old veteran who committed massacres and attacks in Sagaing. How can he return to his home village where all remember what he has done? But any new government needs to integrate such soldiers back into the civilian population and give them a future beyond military service.

In short, Myanmar needs to be taken off a war-fighting footing, which means reducing the peacetime military capacity to one no more powerful than, say, Myanmar’s neighbor, Thailand. Notably, Vietnam claims to have downsized its military by two-thirds, following the conclusion of its wars in the early 1990s. One result is a Vietnam which has reintegrated into ASEAN, with a strong manufacturing economy and great beaches for tourists from ASEAN and beyond. China downsized after the 1949 Chinese Revolution, and again in the 1980s. The United States demobilized after the conclusion of World War II, and the Cold War. Demobilization of the Tatmadaw and the many ethnic armed groups means that soldiers will return to the farm and cities. Secondary and higher education will be an important part of this, as indeed it was in the United States, which demobilized and used government funding to send millions of returned soldiers to technical schools and universities. Perhaps both the US and China could fund such programs in Myanmar.

Great-power détente first

The détente scenario sketched out here may quickly be dismissed as “unrealistic” by American and Chinese diplomats and generals who see Myanmar in terms of their own global interests, rather than its own bundle of contradictions. Both the Chinese and the Americans have for decades seen Myanmar as a sideshow in their larger confrontations over Vietnam, Thailand, Taiwan, the South China Sea, Ukraine, Israel/Hamas, trade policy, etc. But the United States and China really have very little to lose by trying détente in Myanmar. In the broader view from Beijing and Washington, the power squabble in Myanmar is of very little relevance to their confrontations over the South China Sea, Taiwan, or trade policies. But détente may mean that Myanmar can finally chart its own democratic path, and enter into agreements with China to construct railways and other infrastructure in ways that are beneficial to Myanmar.

A post-junta Myanmar will offer a brief window for the Americans and Chinese to recalibrate their approaches in Myanmar. Détente in Myanmar is no less realistic than the Washington Post’s call for Washington to sponsor and thereby subordinate the NUG, Brotherhood Alliance, KNU, KNDF and other potential victors in Myanmar’s wars to America’s broader global interests in challenging China. But for detente to happen, the Washington Post and the US Department of State in Washington need to, perhaps for the first time, see Myanmar as important for its own sake, and not simply another sideshow in their own ongoing confrontations with China.

Tony Waters is a professor of sociology, currently at Leuphana University, Germany. Previously he taught at Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and California State University in Chico, the US. He is an occasional contributor to The Irrawaddy. His email is [email protected].