U.S. lawmakers have taken the moral high ground, demanding that Myanmar’s armed forces be excluded from U.S.-led military exercises in neighboring Thailand next week due to atrocities committed against Rohingya Muslims.

“Simply put, militaries engaged in ethnic cleansing should not be honing their skills alongside U.S. troops,” Senator John McCain, the Republican chair of the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee, told The Associated Press.

After Myanmar’s political opening in 2012, with U.S. blessing, Myanmar officers were granted observer status for the Cobra Gold exercises. Earlier, when Myanmar was under Western sanctions, the generals worried about U.S. intentions, distrusted Thailand and viewed the exercises as a threat.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee has passed legislation authored by McCain and Senator Ben Cardin authorizing sanctions and travel restrictions on more than a dozen senior Myanmar military officials responsible for human rights atrocities against the Rohingya, or Bengali, people. Last month, the U.S. imposed sanctions on Major-General Maung Maung Soe, former head of the Myanmar military’s Western Command, but stopped short of imposing them on the other officers on the list. The official reason for limiting the sanctions to one officer was that U.S. officials were missing date of birth information on the other generals, required under the sanctions legislation. But it may indicate that the sanctions steps are largely symbolic. Will the U.S. consider imposing targeted sanctions on all top brass and their associates?

An opinion piece purportedly written by a Myanmar analyst published in The Diplomat suggested that it was time for the U.S. to engage Myanmar’s moderates after the imposition of the sanctions. But identifying these moderates and finding a way to engage them is a notion likely to draw laughter from many in Myanmar.

Six years ago, then-U.S. President Barack Obama’s administration — which along with other Western governments had been impressed to see Myanmar opening up politically — controversially initiated military-to-military engagement with the Tatmadaw, the country’s armed forces. There was a feeling that Myanmar, once dubbed a client state of China, was moving away from Beijing.

The U.S. and Myanmar embarked on a sophisticated feel-good circus, holding the U.S.-Burma Human Rights Dialogue in the new capital of Naypyitaw a month before Obama made his historic first visit. The pre-visit dialogue was a diplomatic coup for Obama as he prepared to jet in and lavish praise on the “reform”.

Lieutenant-General Francis Wiercinski, the head of the U.S. Armed Forces Pacific Command, and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia Vikram Singh also attended the meeting.

In 2014, Lieutenant-General Anthony Crutchfield, the U.S. Pacific Command deputy commander, was invited to address his counterparts at the Myanmar National Defense College in Naypyitaw, which trains colonels and other high-ranking military officers. In his speech, the senior U.S. officer emphasized human rights and the need for civilian control.

(Photo: Mark Alvarez /U.S. Navy via Stars and Stripes)

The aim of these exchanges, according to the U.S., was to promote human rights and the rule of law.

But then what? How many more activists and journalists have been detained, and how many innocent people have lost their lives since then?

Indeed, this shallow engagement has received a mixed reception in Myanmar, and failed to impress the country’s long-oppressed ethnic minorities.

Many in Myanmar were critical of the engagement, seeing it as premature and counseling caution. Some analysts warned that a slower, more measured approach was needed.

Western scholars cranked out paper after paper urging the U.S. to engage the Tatmadaw. In a paper published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Washington was advised to “…recognize and encourage the Tatmadaw’s cooperative role and foster its professionalization and speedy withdrawal from politics.” Of course, we have seen no indication that the military plans any such withdrawal from politics. To the contrary, it has retained its constitutionally mandated role in national politics.

In another CSIS report released in 2012, a scholar cooed: “If the military continues to support the transition to civilian rule and observes ceasefires in ethnic minority areas, the United States should begin to consider joint military exercises with the Myanmar armed forces and provide selected Myanmar officers access to U.S. international military education and training opportunities in U.S. defense academies.”

General Tin Oo, a former Tatmadaw commander-in-chief and co-founder of the National League for Democracy with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, supported U.S.-Myanmar military cooperation but cautioned that the main duty of the generals should be to protect the country and serve the people. He said he wanted to see Myanmar’s armed forces stay away from politics. Achieving this has proven an impossible task.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who was subsequently elected to Parliament, advocated that military officers receive overseas training. She once said, “After all it was my father [General Aung San] who founded the Burmese Army and I do have a sense of warmth towards the Burmese Army.” But she has little control over what was once her father’s Army.

During a visit to the U.K. in 2013, she spoke at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, where some past Myanmar military officers had studied, and advocated a resumption of overseas training.

Then-U.K. Defense Secretary Philip Hammond said, “The focus of our future defense engagement with Burma will be on the creation of modern armed forces, subject to democratic accountability and compliance with international law.”

So what happened?

In September last year, after the mass exodus in Rakhine State, Britain suspended its educational courses for Myanmar officers on democracy, leadership and the English language – the budget for which is said to be £305,000 (US$411,000). The reason cited — and the subject of the newspaper headlines — was of course the plight of the Rohingya, but the budget could also be a major issue.

“We call on the Burmese Armed Forces to take immediate steps to stop the violence in Rakhine and ensure the protection of all civilians, to allow full access for humanitarian aid,” a British government spokesperson said in a statement.

As expected, the Myanmar Army responded quickly, “We will bring them [the trainees] back to Myanmar as quickly as possible and we will not send trainees to Britain anymore, including those under previous agreements.”

History shows that it was from British instructors that Myanmar Army officers picked up the notorious “four cuts” strategy — whether in London or in Malaysia, where British forces applied this brutal strategy to wipe out insurgents.

The strategy involves the forced resettlement of entire communities and the confinement of villagers in special camps in order to cut off food, intelligence, recruitment and financial support to insurgents. Used by the British to suppress a local insurgency in Myanmar during the colonial period, and included in Myanmar military officers’ in-house training, it is part of Britain’s legacy in this country.

Nor are Myanmar’s generals strangers to the U.S. military establishment.

Gen Kyaw Htin, commander-in-chief of the Tatmadaw from 1977 to 1985, studied at the United States Army Command and General Staff College.

Brig.-Gen Tin Oo (no relation to Gen. Tin Oo), the handpicked aide to former strongman Gen. Ne Win, was trained by the CIA on the Pacific island of Saipan and went on to run one of the most feared and effective military intelligence spy networks in Asia throughout the 1970s and ’80s.

Lt-Gen Tun Kyi and Gen Nyan Linn, both members of the State Law and Order Restoration Council, which staged a coup in 1988, and Col Aung Koe, who also once ran the Military Intelligence unit, all received U.S. military training. Before the 1988 uprising, Washington paid for more than 100 Myanmar officers to attend U.S. military schools. After the military’s brutal suppression of the democracy uprising in 1988, the U.S. suspended military aid and training to Myanmar and downgraded diplomatic ties but maintained its military mission, with the defense attaché remaining in place.

If less overtly ruthless, U.S.-trained generals have displayed greater efficiency and sophistication and played just as important a role as their locally trained colleagues in military campaigns against insurgents and crackdowns on dissidents.

Who is on the targeted list?

Whatever Washington’s plans, the generals are growing increasingly assertive. They have control over the country — including its economy — and do not lack for allies in the region.

Last week, the armed forces completed a three-day major land-sea-air exercise east of Pathein (Bassein) city along the Bay of Bengal, under the Southwestern Command. It is believed that more than 8,000 troops were involved in live-fire drills backed by jet fighters and naval vessels. It was one of the largest military exercises in decades.

Moreover, the military’s procurement plans, strategy and budget, as well as its efforts to build alliances, have diversified.

Myanmar recently bought six SU-30 advanced jet fighters from Russia. Moscow and New Delhi have provided training, and Myanmar’s ties to regional armies including those of Thailand and Japan have strengthened. Just this week Indonesia agreed to provide counterterrorism training to Myanmar as threats in the region grow. Officers have been sent to study in Russia, and more recently in India and Japan.

Recently, China and Myanmar agreed to increase military cooperation, though suspicion of China remains strong among Myanmar generals. Until last year, Tatmadaw chief Min Aung Hlaing was invited to the EU to deliver speeches, perhaps as part of efforts to give greater exposure to the “isolated senior general”. He defended the Constitution and echoed his former bosses’ policies, stating frankly that “people from Bengal”—a term also used to described self-identifying Rohingya in the region—were “not included” among Myanmar’s ethnic minorities. It seemed he didn’t give a damn about what the West was thinking.

What about the U.S.? Obviously, Washington had been eager to expand military-to-military cooperation, as stated by its diplomats and officials. Since the political opening in Myanmar, military officers have attended the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Hawaii.

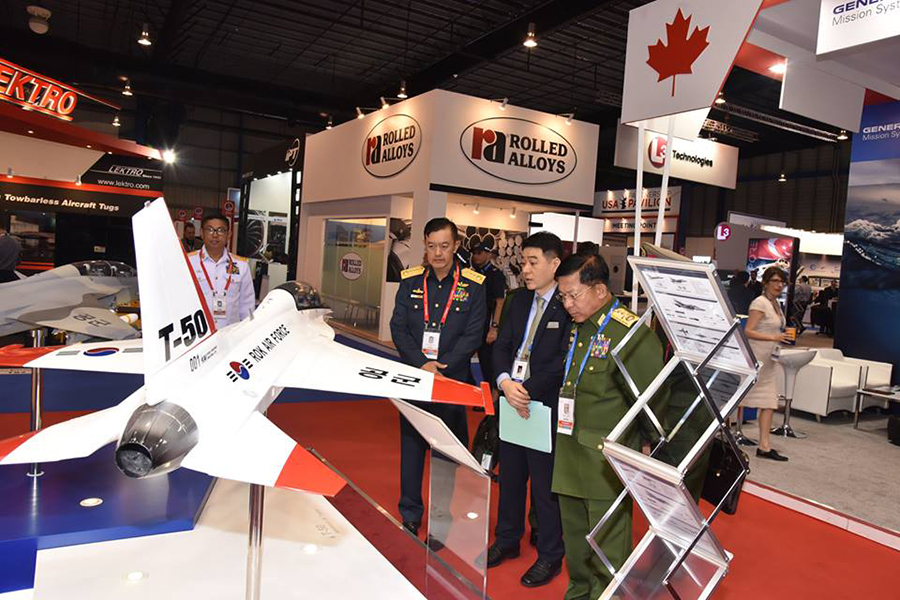

This week, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, chief of Myanmar’s armed forces, flew to Singapore to attend the Singapore Airshow 2018. Some have speculated that his real ambition is to travel to Washington, visit the Pentagon and have his picture taken aboard a U.S. aircraft carrier. Indeed, before the bloody crackdown in Rakhine State, U.S. officials had intended to invite some senior generals to Washington. Like many U.S. officials, Senator McCain had been in favor of closer military cooperation, but he appears to have changed his position. Last year, Min Aung Hlaing was also in Israel for an arms “shopping trip”, and Israel was selling. Myanmar and Israel have enjoyed long-lasting relations for decades and Israel openly agreed to provide security equipment to Myanmar.

At home, meanwhile, the war machine grinds on.

In the North, over 100,000 people have been displaced from their homes since a 17-year ceasefire between the central government and Kachin insurgents collapsed in 2011.

Tensions there have only increased of late. At a recent meeting in China, the military asked the Kachin Independence Army to withdraw from its bases in Kachin State’s Tanai Township, where the two sides have engaged in intense fighting in recent weeks. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs says the Tatmadaw has restricted humanitarian access to Tanai and that it remains concerned about the area’s civilian population.

The war in the north is likely to escalate. In Rakhine, countless reports of mass graves and tales of human rights violations have emerged.

In his 2014 speech to the Defense College in Naypyitaw, Lt-Gen Crutchfield, the U.S. Pacific Command deputy commander, said — according to the U.S. Embassy — “My presence here is indicative of the new chapter in our countries’ relationship.”

Did the more than 100 military officers Crutchfield was addressing suffer from Alzheimer’s disease or have collective hearing problems? Probably not.

A few years ago, when self-appointed Myanmar analysts were trying to debate how to engage the military, one scholar suggested trying to convince future generations of military leaders that the proper place for generals is the barracks, not politics.

The idea that “moderates” should be engaged is absurd at a time when the military is seeking to modernize its forces, and sees its mission as holding the country together, keeping insurgents at bay and safeguarding the country’s sovereignty. Flanked by powerful neighbors, Myanmar’s military leaders are focused on building an Army, Navy and Air Force with modern and advanced hardware to deter threats.

So, when it comes to engagement, who was the first to drink the Kool-Aid?