Many people cling to the notion that dialogue, or some other form of negotiation, holds out the only hope of bridging Myanmar’s decades-long divide between the military and civilian political forces. The idea took root—domestically and internationally—even before the military staged its bloody coup in 1988, and it has remained fashionable ever since. But while top leaders on both sides have met many times, to date we can’t say these meetings have contained any genuine political dialogue.

In August 1988, shortly before her entrance into politics during the nationwide pro-democracy uprising that year, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi attempted to initiate a dialogue with the Ne Win government in order to find a peaceful solution to the ongoing student protests at the time. Her personal request never received a reply.

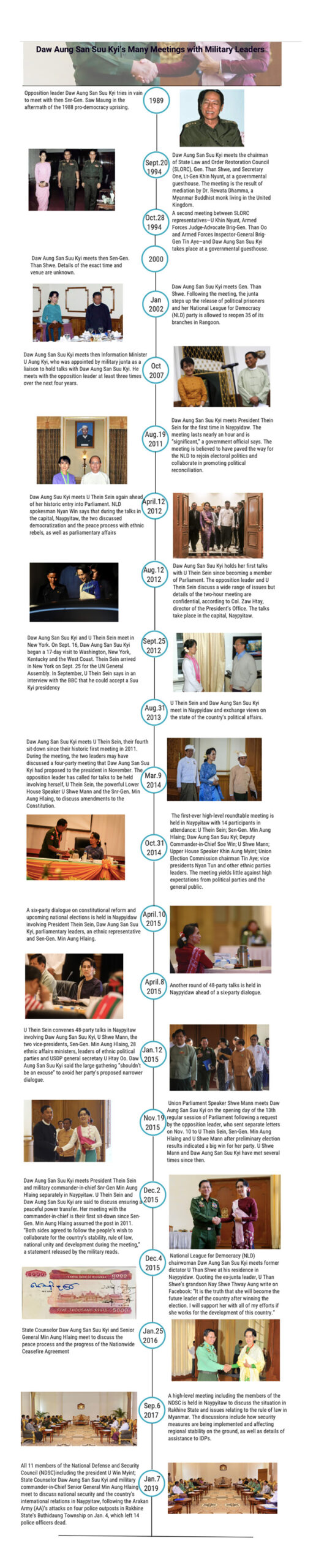

Over the past three decades, scores of meetings have occurred between Daw Aung San Suu Kyi—whether she has been acting in her capacity as pro-democracy leader, opposition leader, or her current role as incumbent de facto head of government—and a small group of top ruling generals representing either the military or its various regimes: Senior-General Than Shwe, his deputy Vice Senior-General Maung Aye, General Khin Nyunt, and later retired general-turned President U Thein Sein and the current military chief, Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing (see chart below).

These many meetings failed to produce any concrete political results whatsoever, or even any indication that serious dialogue aimed at resolving the country’s main political problems took place. They were widely dismissed as photo-ops for the ex-regimes aimed at creating the impression, domestically and internationally, that political dialogue exists in Myanmar.

Looking back, it all seems to have been little more than a charade.

In late January when the ruling National League for Democracy led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi initiated its move to form a joint committee to amend the 2008 Constitution drafted by the former military regime, the military representatives in the Union Parliament appointed by the commander-in-chief, who account for 25 percent of lawmakers, joined the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) formed by ex-generals in unanimously objecting to it.

Some analysts have expressed the view that the NLD on one side and the military and USDP on the other should discuss the issue instead of confronting each other in Parliament. This is a fine view in principle, but in practical terms it is hard to support, because no such negotiation has occurred in Myanmar’s history.

Some people think dialogue doesn’t happen in Myanmar because the country doesn’t have a “culture of dialogue”. In fact, such dialogue doesn’t require a “culture”. All it requires is political will. If genuine political will to resolve problems existed on both sides, holding a dialogue would be easy. That is to say, the lack of dialogue so far points to a lack of political will among the leaders on one or both sides. Why? Because they don’t want to change the political status quo. Who? History shows that the ex-generals, despite meeting with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi many times, have never seriously been open to dialogue.

After Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won a landslide victory in the 1990 general election, the international community, including the UN, urged the ruling generals to enter a dialogue with her. That’s what she and many political groups demanded in order to resolve the country’s political problems together. But nothing serious happened.

Recalling his meetings with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the ruling generals, Razali Ismail, who served as UN Special Envoy from 2000 to 2005, once quoted Daw Aung San Suu Kyi as saying: “The dinner with the generals was in fact a monologue with the senior general doing all the talking,” referring to the then military supremo Than Shwe.

Many years after the events recalled by Razali, we have yet to see any significant change in the military leadership’s attitude toward “dialogue.” Even the presence of a so-called “reformist” ex-general, U Thein Sein, as president between 2011 and early 2016 failed to deliver any serious dialogue, though meetings were held. (Yes, there was a meeting between U Thein Sein and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in August 2011 that led the NLD to take part in the 2012 by-election and enter Parliament. But a series of meetings on national reconciliation later bore no fruit.)

Later, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and military commander-in-chief Snr-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing met several times before and after her party took power in early 2016. Again, the meetings failed to evolve into dialogue.

So it would be unreasonable to expect dialogue or negotiation between the civilian and military to emerge from the constitutional reform initiated by the NLD to fulfill the promise it made during the 2015 election campaign.

Against this background, it seems, the NLD had no choice but to initiate the formation of the joint committee to reform the Constitution in January. The move has gained support from the public and ethnic parties, while the military and the USDP have strongly rejected it. Forming the joint committee in the Union Parliament was a way of forcing the military to engage with the topic of constitutional reform.

Some analysts doubt that this political push by the NLD will have any significant results. True, we shouldn’t expect too much from it because the current Constitution protects the military’s interests. On the other hand, given the popular support for reform, we shouldn’t be too quick to predict total failure. The NLD is taking the only political option available to it. History shows that Myanmar’s former and current military leaders have never been genuinely interested in negotiation, especially when its own interests are likely to be on the table.