Is it strange to see Myanmar’s top general visiting mosques and churches making donations and meeting religious leaders?

The answer, probably, is “yes”. But get used to it: Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and his team have unleashed an orchestrated public relations campaign to woo non-Buddhist communities in Myanmar.

Like a commander planning a military campaign, Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing launched the first phase of this charm offensive a few weeks ago when he visited Christian and Muslim religious groups in Pyinmana, near the capital Naypyitaw. The response to the first visit seemed positive (the military is usually careful to gauge local and social media reaction to such moves), so the military chief followed it with trips to larger cities such as Mandalay and Yangon, where he made donations. In Yangon he also visited the shrine of Bahadur Shah Zafar—the last Mughal emperor, who died in exile in Myanmar in 1862—to make a donation. Accompanied by his wife and top-ranking generals, Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing also visited and made donations at Buddhist monasteries, a Christian home for elderly people, the Muslim Free Hospital and a Hindu temple.

The public relations campaign, which is designed to counter domestic and international allegations of religious persecution, has been welcomed by some quarters of the Christian and Muslim religious communities in Myanmar.

“Our country needs to be united now. In particular, we need political cohesion, social cohesion and religious cohesion today. [The Myanmar military] has done what is necessary for that,” military (or Tatmadaw) spokesperson Brigadier-General Zaw Min Tun told The Irrawaddy, explaining the rationale for the army’s handing out of donations to non-Buddhist religious organizations.

Critics say the show of good will is intended purely to counter the international allegations of religious discrimination, and is a reaction to recent Western sanctions. However, a coordinated “counteroffensive” strategy can be seen in the recent visits to churches and mosques, perhaps engineered by the top-ranking generals close to Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing with an eye on Myanmar’s general election scheduled for 2020. The commander-in-chief is trying to show that he is ahead of the game and capable of outflanking critics and opponents.

A general accused of genocide visits a mosque: This is headline news and will no doubt come as a surprise to some—and even anger many activists who would like nothing more than to see Myanmar punished.

With its bold move to demonstrate to critics at home and abroad that Myanmar enjoys religious freedom, one could even mistake the military for a political “opposition” to the ruling party and the government.

Since late 2017, international calls have grown for Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing to be tried at the International Criminal Court (ICC) for human rights violations committed against Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslim people, more than 700,000 of whom are now in Bangladesh after fleeing the military’s clearance operations in the wake of Muslim insurgent attacks on police outposts in that year.

Recently, Washington also imposed sanctions on Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing and some other senior military officials, barring them and their families from entering the US. The Myanmar military has described the US sanctions as an act of bullying.

Unsurprisingly, Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing’s visits to meet non-Buddhist communities coincided with a report released Monday by a UN fact-finding mission, which repeated calls for the country’s top generals to face trial. “The threat of genocide is continuing for the [Rohingya remaining in Myanmar],” Australian human rights lawyer and panel member Christopher Sidoti said in a statement accompanying the new report issued in Geneva. He added that Myanmar was failing to prevent and punish genocide.

For their part, the generals appear to have softened their stance toward some critics of late.

Last week, the military dropped a lawsuit against an ethnic Kachin religious leader who discussed religious freedom with US President Donald Trump at the White House last month and asked him to support Myanmar’s transition to “genuine” democracy and federalism. The US State Department voiced concern about the case.

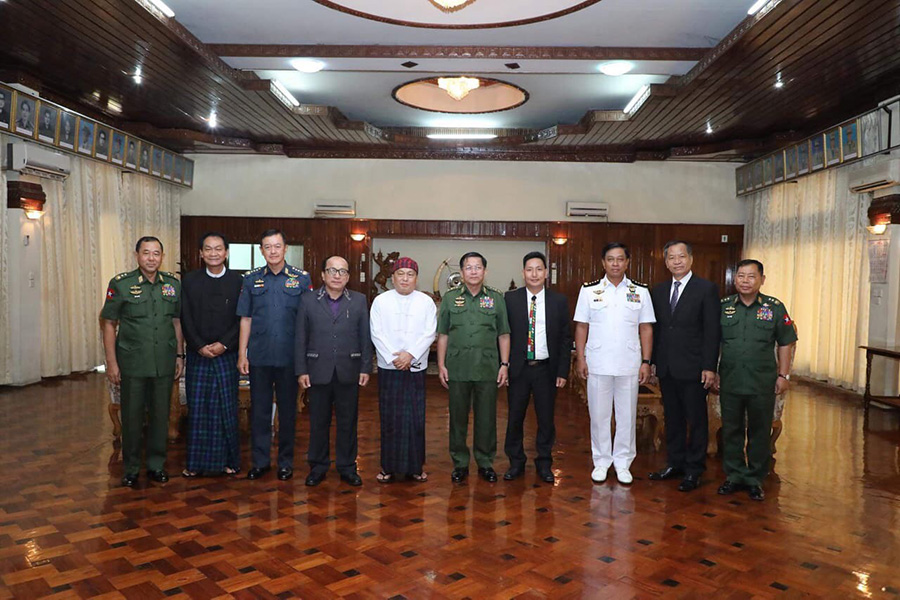

After dropping the charges, Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing then held a meeting with Rev. Dr. Hkalam Samson, president of the Kachin Baptist Convention (KBC), in Mandalay.

According to a military spokesperson, the military withdrew the case of its own free will, saying the decision was not due to any outside pressure. Indeed, this is a standard response from the military in such situations.

But it seemed the meeting between Rev. Dr. Hkalam Samson and Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing produced a good outcome.

Informed sources close to the military said army leaders realized that the legal action against Kachin religious leaders only provided more ammunition to campaign activists and lobbyists outside Myanmar, who want to see harsher sanctions and a return to isolation for Myanmar. This is not in the interests of the generals or the general population.

In any case, how Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing will go about restoring his image, which has been tarnished by the Rohingya crisis and his association with so-called Buddhist nationalist groups, remains to be seen.

In June, the chief of the Tatmadaw’s Yangon Regional Military Command donated 30 million kyats (about US$19,600) to Myanmar’s leading Buddhist nationalist group (still widely known by its Burmese former acronym Ma Ba Tha), which has denounced the government for its prosecution of ultranationalist monk U Wirathu. The fugitive monk is wanted by the government and believed to be in hiding.

A few months ago, large photos of Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing were proudly carried by the front row of a group of demonstrators dubbed “ultranationalists” for their association with Ma Ba Tha as they marched down a Yangon street. Will they be carrying his picture at their next rally? Or will they denounce him?

It is interesting to note that a visit to a mosque by State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi would invite an outcry and malicious attacks from many sides, especially from pro-military groups, even though it is she who has unwaveringly espoused the need for national reconciliation, diversity, peace and religious tolerance.

Under her administration, Pope Francis visited the country in November 2017 and said after meeting Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, “The future of Myanmar must be peace, a peace based on respect for the dignity and rights of each member of society, respect for each ethnic group and its identity.”

He added, “Religious differences need not be a source of division and distrust, but rather a force for unity, forgiveness, tolerance and wise nation-building.”

During the visit, the 82-year-old pontiff also received a “courtesy visit” from Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, though the visit was unscheduled and no publicity photos were issued.

According to a Facebook post published by the senior general’s office a few hours after the meeting, the army chief told the pope that, “Myanmar has no religious discrimination at all. Likewise, our military too … performs for the peace and stability of the country.” He added that there is also “no discrimination between ethnic groups in Myanmar”.

Everyone—including some Christian military officers—would like to believe Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing’s words, as the Tatmadaw has had an unwritten but systematic policy of not promoting non-Buddhist officers to the highest levels for the past two decades.

In any case, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi stands by her principles, which remain unchanged.

In May, in her opening remarks to the Forum on National Reconciliation and Peace in Myanmar organized by the group Religion for Peace-Myanmar (RfP), Daw Aung San Suu Kyi urged people to respect the country’s different faiths.

Pointing out that Myanmar hosts a diversity of ethnic groups with various religious beliefs, she said that “mutual respect among the different races and religions” will “improve peaceful and stable livelihoods and…prevent religious conflict.”

The irony is that the recent visits to mosques and churches by Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing should offer comfort to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who has found herself increasingly caught between religious nationalists and the still powerful military.

The question now is: What is the difference between the two? Is the gap narrowing? Or is the senior general’s gambit merely aimed at wooing voters ahead of the 2020 election? Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing is known to have presidential ambitions, but has kept his strategy and precise thoughts to himself and a few aides.

Myanmar’s traditional and mainstream Muslim population, who are uncomfortable with the nationalists’ rhetoric while also not wanting to be associated with Rohingya Muslims, will no doubt be pleased with Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing’s visits, however superficial.

The military has made its message official: the country needs to be united, with political, social and religious cohesion. Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing must now keep his promises.

You May Also Like These Stories:

Myanmar Military Chief Meets Kachin Religious Leader

Myanmar Military Chief Makes More Donations to Non-Buddhist Groups