Myitsone Dam—just another damned problem for Myanmar. Or is it? This issue in particular seems to have both constructive and destructive potential; politically, it could save or slay a leader of this country.

Former President U Thein Sein—who, as a general of the former oppressive junta came to power with only limited public support in 2011—saw that support grow when he suspended the Myitsone project in September of that year. The former general cleverly chose that path, though his bosses in the ex-regime had agreed with China on the project in 2006 and started it in late 2009. Myitsone saved his political popularity.

Eight years later, this controversial issue inescapably confronts the country’s popular de facto leader, State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. It is her turn. The question is whether the Myitsone project will save or slay her politically.

If she saves Myitsone, it seems, Myitsone will save her.

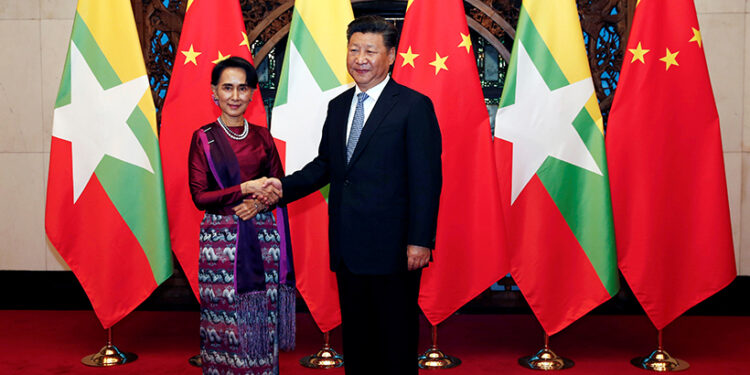

Even now, as she prepares to travel to Beijing this month to attend the 2nd Belt and Road Forum, people have no clue as to what she has in mind for the project. During her meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping there, the Myitsone issue will be high on their agenda, for it’s one of the most controversial Chinese-backed projects in Myanmar. Obviously, many people from all walks of life across the country have very strong feelings on the issue, and want to know whether Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her government plan to revive the suspended project, the initial agreement on which was signed with China’s State Power Investment Corporation.

On April 1, about 200 prominent environmentalists, intellectuals, civil society leaders and experienced writers from different regions of the country held a meeting in Yangon. They formed the Committee to Terminate the Myitsone Project and issued a strong statement urging the government to scrap it. In a statement, they warned that reviving the project would disrupt the country’s ongoing democratic transition and hinder national reconciliation.

The Myitsone Dam project would be among the largest hydropower projects in the region, costing US$3.6 billion (5.4 trillion kyats). The dam itself, which would be built about 3.2 km south of where the confluence of the May Kha and Mali Kha rivers gives rise to the Irrawaddy River, would disrupt the water flow of the river. Environmentalists say the proposed dam site has one of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world, and fear the project would destroy the natural beauty of the Irrawaddy River, as well as alter its flow. It could potentially flood an area the size of Singapore, destroying livelihoods and displacing more than 10,000 people.

For some time, the majority of people in Myanmar had been under the impression that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi would not revive the project, given the opaque nature of the deal signed by the military regime with China. She certainly sounded critical of the project before her National League for Democracy took office in 2016.

On Aug. 11, 2011, she published an open letter to then-President U Thein Sein appealing to him to review the project in order to avoid unnecessary consequences and to find a joint solution that could allay the concerns of people who want to save the Irrawaddy River. Her letter may have influenced his decision to suspend the project when he officially announced the move a month later.

Today, however, the public is getting mixed signals from their leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. It was this ambiguous messaging that prompted the formation of the committee to prepare resistance against the project in case her ruling government decides to revive it.

In a meeting with local people in Bago Region in March, when asked for her opinion on the proposed dam, she answered, “I would like you to think about it from a wider perspective.” She went on to say that the final decision would have to be politically, socially, economically and environmentally sound and sustainable.

This sounds reasonable and pragmatic, but what she should understand is that the Myitsone project goes beyond those boundaries. Besides political, social, economic and environmental factors, Myitsone is also a sentimental and national issue for the majority of people across the country. Building a mega dam near the source of Myanmar’s lifeline Irrawaddy River would destroy one of the country’s national symbols.

In January, U Thaung Tun, the Minister of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations and a key economic aide to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, said the government and a commission studying the project were in very serious discussions and considering all possibilities, including downsizing the dam, relocating it or developing other projects instead.

But many people don’t seem inclined to accept any alternative to the Myitsone project other than terminating it. Apart from the factors mentioned above, they have no confidence in China at all. Many people, including critics of the Myitsone project, may be willing to tolerate other Chinese projects across the country, but they simply say “NO” to Myitsone.

Meanwhile, the NLD government—which is already engulfed in such crucial issues as the peace process; ongoing conflicts in border areas; the fallout from the Rohingya crisis of 2017 including the resultant international condemnation and economic slowdown; and intensifying clashes between the Arakan Army and government troops in Rakhine State, among other problems—faces the dilemma of reviving the dam or saying no to China, which has shielded the government from some of the consequences of the international condemnation over human-rights violations by the Army.

What Daw Aung San Suu Kyi should understand is that the Myitsone issue is categorically different from other issues. She can’t only consider practical factors involving political, social, economic and environmental issues. She must also take into serious consideration less material concerns and the Myanmar people’s emotional attachment to the Irrawaddy River.

Given the mounting popular opposition to the dam project, any green light for its resumption would be political suicide for the Myanmar State Counselor. With a general election looming next year, it would surely be an electoral nightmare for the NLD. Perhaps worst of all for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, she would be putting at risk her status as the “People’s Leader” of Myanmar—a title unanimously endorsed by the people.