Chinese foreign minister Qin Gang’s first visit to Naypyitaw signals that Beijing intends to step up its engagement with the Myanmar regime. This high-level visit will be watched closely.

Ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the north, opposition forces inside and outside the country and the parallel National Unity Government (NUG) will be anxious to see the results of this increased engagement, which will certainly not be a one-way street. We will see.

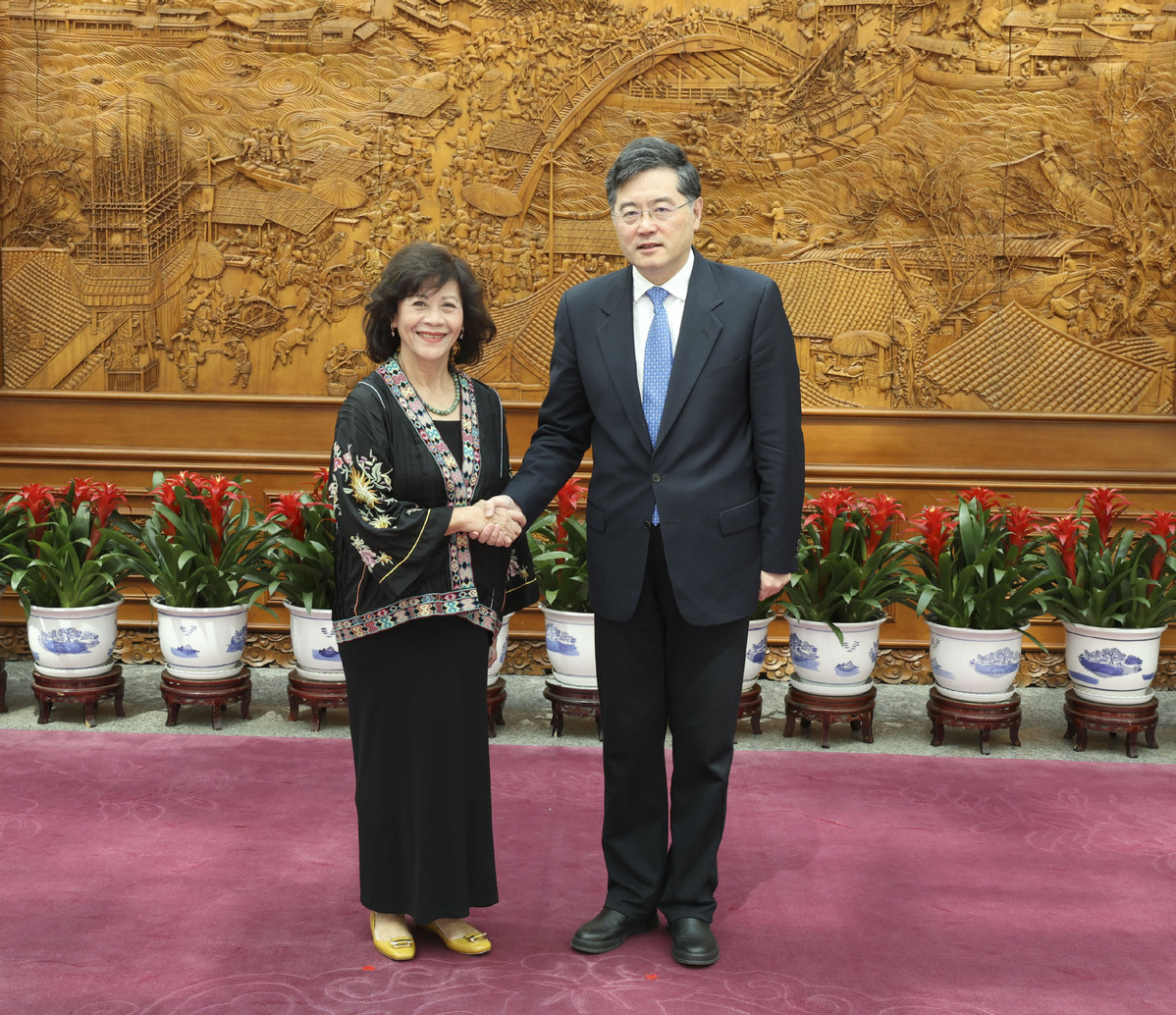

In Beijing, before coming to Myanmar Qin Gang met with Noeleen Heyzer, special envoy of the UN secretary-general on Myanmar.

Qin said the Myanmar issue is complex and has no “quick fix.” He called on the international community to respect Myanmar’s sovereignty and support all parties in the country, within constitutional and legal frameworks, to bridge differences and resume the political transition process through political dialogue.

Qin also said that the international community should respect the mediation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and promote the implementation of its Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar. The irony is that China has unwaveringly defended past and present regimes, including the current State Administration Council (SAC), at the UN Security Council (UNSC) as if Myanmar was one of its provinces.

He also paid a rare visit to the China-Myanmar border before coming to Myanmar. During the border visit, Qin called on local communist party, police and government departments to join in “strengthening the border defense system.”

He called for improvements in “maintaining distinct and stable borders, and a severe crackdown on cross-border criminal activities.”

“It is necessary to coordinate border management, border trade development, and bilateral relations,” he was quoted as saying in a ministry news release.

In any case, it is important to note that Beijing has its own game plan for Myanmar.

Last week, Myanmar Ambassador U Tin Maung Swe presented his credentials to Chinese President Xi Jinping—a sign of Beijing’s recognition of the brutal and appalling regime in Myanmar.

Prior to that the regime’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced it welcomed Xi’s Global Security initiative (GSI), saying it is “a visionary initiative, and its commitments conform to the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence, including respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity and non-interference that Myanmar consistently adheres to in conducting its foreign policy.”

In December, Deng Xijun, China’s special envoy, visited Myanmar and met with junta leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Deng also held several meetings with ethnic armies from northern Myanmar based along the Chinese border. It was one of two recent trips he has made to the country.

Expanding Northern Alliance ties

But the Chinese have not overlooked their friends in the north.

On the northern border Deng held separate meetings with representatives of the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP), the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA).

These EAOs are under the sway of China, and three of them—the KIA, TNLA and MNDAA—based in northeast Myanmar’s Shan State are actively fighting the regime. The Wa continue to sell arms and ammunition to resistance forces under the NUG including the People Defense Force groups (PDFs) active in central Myanmar and in the north.

Since December, several Chinese officials from Yunnan Province have visited the headquarters of the ethnic armed groups and held broad discussions on a ceasefire, the political landscape in Myanmar, border trade, and expanding their friendship. Through the Northern Alliance network senior Chinese officials from Yunnan Province also recently made overtures to NUG representatives.

During meetings with Northern Alliance forces Chinese officials have spoken frankly, expressing their growing concerns about the instability in Myanmar. The Chinese think Min Aung Hlaing is on a road to nowhere and have stepped up their engagement with the Alliance to expand their influence.

Analysts noted that the recent flurry of high-profile visits by China took place soon after the US Congress’ passage of the Burma Act.

The Act authorizes funds and technical assistance for anti-junta forces in Myanmar, including EAOs. The US has pledged to continue to support opposition forces inside and outside of Myanmar.

In Southeast Asia, Myanmar is contested territory in the US-China rivalry. China is concerned with growing Western-oriented democratic opposition in and out of the country, as well as Myanmar’s Spring Revolution.

In any case, Beijing has consolidated its influence in the northern region, particularly in Shan and Kachin states.

China sees junta not in full control

The Chinese realize the conflict in Myanmar will be long and protracted and doubt Snr Gen Min Aung Hlaing’s ability to control the country after seeing the extension of the emergency period and his forces’ loss of control over territory. Under the current circumstances, there is a danger that the fire could spread to Myanmar’s neighbors, including China.

In mid-April, Peng Xiubin, the director of the International Liaison Department of the Communist Party of China, traveled to Naypyitaw and held two unpublicized meetings with former junta leader Than Shwe and Thein Sein, the president of Myanmar’s quasi-civilian government from 2011 to 2016. Thein Sein’s political reforms were praised at home and abroad.

Than Shwe is an architect of the 2008 military-drafted constitution and Thein Sein was instrumental in implementing the gradual, military-guided opening of the political transition that began in 2011. Unlike Min Aung Hlaing, who has openly expressed anti-China feeling, former junta supremo Than Shwe cultivated deep and long-lasting ties with China.

This shows that China has access to the inner circle of leaders of the past and present regimes. But why would Chinese officials want to meet Than Shwe and Thein Sein? Perhaps Beijing thinks Than Shwe can still influence Min Aung Hlaing to change course.

But would Than Shwe place himself at risk by telling Min Aung Hlaing to change his ways or step down? It is doubtful.

Yunnan to expand business ties

In early April, Wang Ning, a member of the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s Central Committee and secretary of the CPC Yunnan Provincial Committee, visited Myanmar. He also met with Min Aung Hlaing, but his request to meet detained State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was denied. Chinese officials also said they were not happy with the disbandment of the National League for Democracy (NLD), which China continues to engage.

During his visit, China signed a power purchase agreement for hydropower plants, as well as agreements on rice, agricultural produce and fertilizer trade, with the junta-appointed ministers for electricity, agriculture, livestock and irrigation, energy, and commerce. Agreements on infrastructure projects were also reached. It is expected that more and more business from Yunnan Province will come to Myanmar.

China has huge economic and geopolitical interests in Myanmar and has invested heavily in natural resources such as oil, gas, timber, and minerals in the country. Community leaders are concerned that China always exploits Myanmar’s natural resources without any concern for the fate of the local population.

Myanmar is a key part of Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI), hosting several major infrastructure projects including the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC).

The CMEC includes a deep-sea port at Kyaukphyu, an industrial park, and a high-speed rail link between Kunming in China and Mandalay in Myanmar. Many of these projects have stalled since the coup.

Chinese government officials, the regime and the business community in Myanmar want to implement cross-border development schemes, restart major infrastructure and connectivity projects and address electricity shortages in Myanmar.

It is believed that in the near future China and Myanmar will sign agreements on several projects including economic zones, agricultural and commercial industrial parks, and an upgrade of the Mandalay-Muse Road.

This shows China is confident that resistance forces and ethnic insurgents will not harm Chinese interests in the country. But can China fully trust all ethnic armed forces in the north? Perhaps not.

But cozying up to the regime will come with a price tag.

Soon after the coup in 2021, massive anti-China protests erupted as anti-China sentiment swelled in Myanmar, with many believing Beijing had a hand in the takeover. Along with calls for a boycott of Chinese products, there were calls to blow up the pipelines if China refused to condemn the regime. Chinese factories in Yangon were attacked.

Youth across the country have also launched campaigns to boycott Chinese products and called on Myanmar employees of large Chinese projects to participate in the Civil Disobedience Movement to show their opposition to the military regime.

In response to the increasing anger directed at Beijing, China’s ambassador to Myanmar, Chen Hai, told local media that the situation in the country is “absolutely not what China wants to see.”

China’s increased engagement with the vicious regime in Myanmar will receive condemnation and will not go down well with the majority of Myanmar people, who loathe the regime and oppose the coup. However, under Beijing’s more balanced approach to the Myanmar crisis it will try to cultivate more friends and engage with all parties. Can China really balance its engagement? China still wants to bet and will side with whoever wins the conflict. However, Qin’s note of caution that the Myanmar issue is complex and has no “quick fix”, delivered prior to landing in Myanmar, is significant.

So what can we expect from China?

Beijing will expand its influence and leverage over the trajectory of the Myanmar conflict. On one hand, it will continue to consolidate its ties with the Northern Alliance, meaning we can expect more economic engagement and expanding autonomy in Kachin and Shan states; on the other, China will increase its engagement with the reviled and isolated regime in Naypyitaw, lending it undeserved legitimacy. For China, its own interests come first and at the end of the day it will side with the winner—whoever it is.

For now, though, Beijing is happy to engage with “all parties” in Myanmar.