Myanmar will hold its general election in November. All signs indicate that the ruling party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), will be returned to power. That shouldn’t surprise Myanmar’s neighbors and other countries in the region, including China, India and Japan.

With the country currently experiencing a spike in COVID-19 cases, whether it will manage to hold the election on the scheduled date of Nov. 8 remains to be seen. One thing we can be sure of, however, is that China will be betting on the NLD and its leader, State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Indeed, as the election draws near, Naypyitaw has received a series of high-profile visitors.

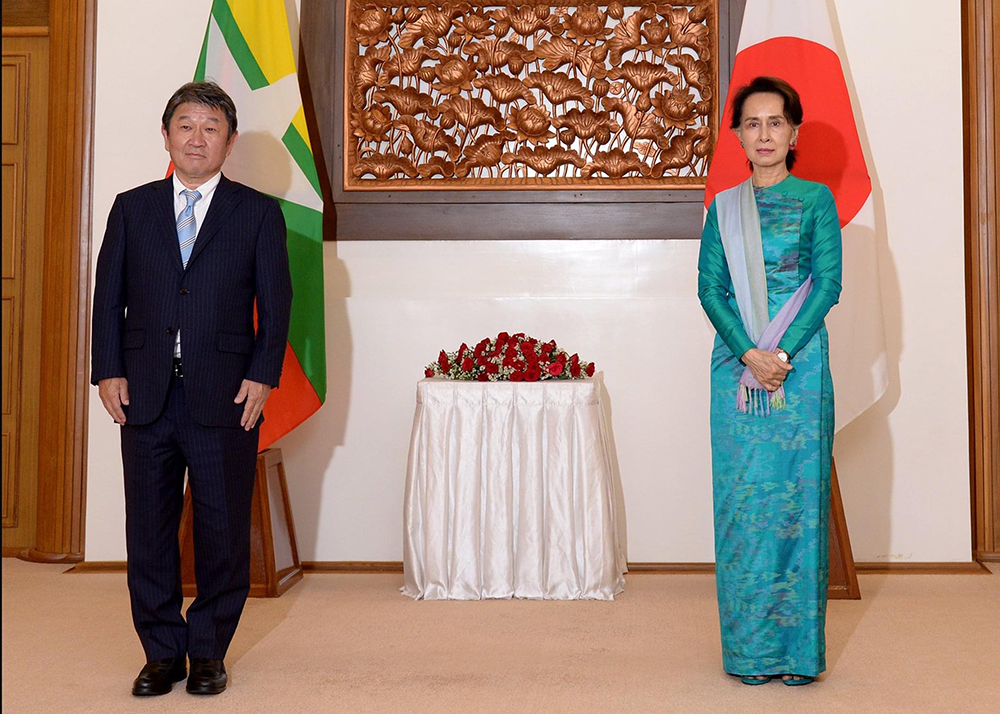

Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi paid a visit, announcing emergency loans and discussing a range of issues including the need for a free and fair election, reopening the country’s borders to long-term residents and businesspeople, and financial support to help improve conditions in Rakhine State.

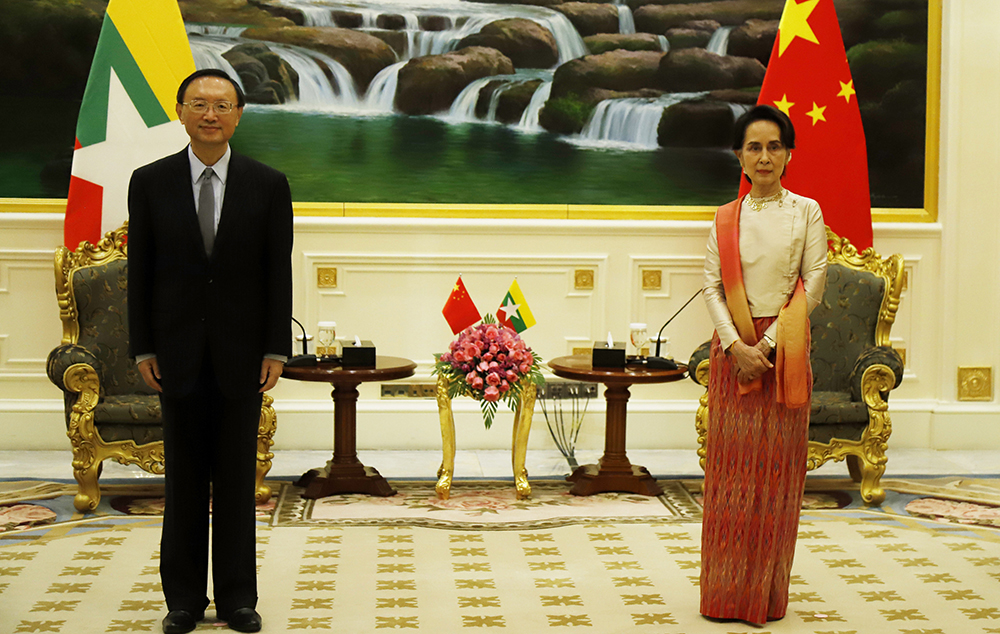

A week later, Yang Jiechi, a member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s Central Committee and director of the committee’s Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission, was in Naypyitaw, where he met President U Win Myint, State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and armed forces commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

The senior Chinese diplomat called for a strengthening of high-level exchanges, and for the consolidation and deepening of political trust between the two countries. The aim of the visit was to promote and speed up implementation of the long-delayed China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) projects, which form part of Bejing’s vast international infrastructure scheme, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Jiechi also said China is also willing to give priority to sharing a COVID-19 vaccine with Myanmar once it is developed.

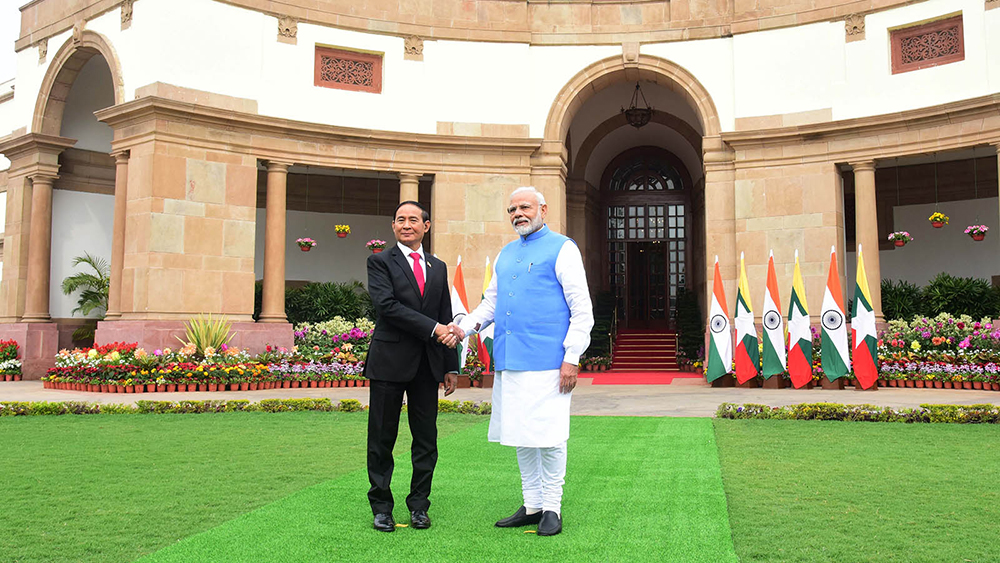

This month, senior officials from India are also scheduled to visit Myanmar, though no details have materialized yet.

China, Japan and India are Myanmar’s most important allies in the region and will be keenly following the results of the upcoming election.

The US, too, has a stake in the outcome. Over the past three decades, it has invested in the democracy movement in Myanmar and gained considerable influence inside the country. Washington cannot afford to see this process reversed.

The US Embassy in Yangon announced that the US government has provided more than US$46 million (61.22 billion kyats) to the Union Election Commission (UEC), civil society groups and political parties to administer and participate in the 2020 election.

China makes a move

Myanmar was the first country to welcome President Xi Jinping on an overseas visit in 2020, as the Chinese leader made the country the first item on his well-choreographed diplomatic calendar for the year.

The visit was in part timed to mark the 70th anniversary of diplomatic ties between Myanmar and China this year. In an op-ed published in Myanmar’s state-run media during the visit, Xi said China supports Myanmar in “safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests and national dignity.”

Behind the pomp of the visit, and the accompanying sugar-coated messages and state-sponsored reception, Chinese officials confided that they respect Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her political stance. They also said that compared to the notoriously corrupt generals that ran the previous regime, the Chinese find Daw Aung San Suu Kyi pragmatic and believe she will keep her promises (on Chinese-funded projects in Myanmar).

China made an unmistakable shift in 2015, adopting a pro-active foreign policy towards Myanmar, months before the country held its election in November of that year. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, then opposition leader and a member of Parliament, was invited to Beijing, where she met with Xi. The NLD subsequently won a landslide election.

By inviting Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to China, Beijing sent a signal to the military and long-time allies in Myanmar, including the military-backed Union Solidarity Development Party (USDP), that it is capable of making new friends in Myanmar. The invitation also sent a message to the West that Beijing is pragmatic in dealing with Myanmar and understands the necessities of geostrategic competition.

For a number of years, the Communist Party of China and the USDP developed close party-to-party relations. In 2012, then Vice President Xi met with U Htay Oo, then Secretary-General of Myanmar’s ruling USDP, in Beijing, vowing to boost inter-party ties. “China has always handled its relations with Myanmar from a strategic perspective,” the Chinese vice president told U Htay Oo in the Great Hall of the People. This was the last high-profile meeting between the CPC and USDP.

Courting the NLD

In fact, in the past, China cultivated deep friendships with the leaders of the former military regime and the military elite. The Chinese Embassy in Yangon was close to the military regime and in constant contact—reports of a flurry of meetings between the two sides were published in state-run papers. (A downside of the friendship, however, was a rise in anti-China sentiment among Myanmar’s oppressed citizens.)

But this has changed since the NLD won a landslide election in 2015. China has taken steps to strengthen ties with the NLD government and the ruling party.

According to NLD sources, more than 100 NLD members including key players, lawmakers and youth wing members have visited China since 2016. The number of delegates visiting China has outpaced those from the US, EU and Asian countries. Usually they first fly to Beijing and other provinces and end their trips in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, which shares a border with Myanmar.

Along the way, Myanmar delegates study the CPC’s leadership model and China’s economic and social reforms, according to NLD delegates who have visited the country.

An NLD Central Executive Committee member previously told The Irrawaddy that the NLD has built a constructive relationship with China amid growing tensions with Western countries over the Rohingya issue. Seizing the advantage, China has also promoted its own agenda of investments and projects, showing the visitors mega-dams and other development projects.

There is no doubt that China will continue to bet on Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD. After the 1990 election, then-Chinese Ambassador Cheng Ruisheng was the first diplomat to call NLD headquarters in Yangon to offer congratulations, though the regime never honored the outcome.

Influence with EAOs

Moreover, China maintains regular contact with armed ethnic minorities in northern Myanmar. In fact, China has far more influence over ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the north than Myanmar’s own mainstream political parties, including the NLD.

Over the past few decades, many ethnic armed groups have become dependent on China for political and economic support, as well as arms. This has left them indebted to the country. Unable to refuse their patron’s requests, they have become China’s foot soldiers in Myanmar. Through these armed groups China has been able to exert influence—albeit limited—on some ethnic political parties in the ethnic regions.

In Yangon, the Chinese Embassy maintains regular contact with organizations such as the Myanmar Chinese Chamber of Commerce, as well as NLD leaders, top-ranking government officials and the military, though it no longer has the kind of broad-based contacts it once enjoyed among Myanmar politicians, influential writers and “Red China” sympathizers in the 1950s and 1960s.

The US, meanwhile, has built up influence through a network of contacts throughout Yangon and Myanmar in recent years, in the wake of the country’s political opening.

Nonetheless, China’s influence on Myanmar, both direct and indirect, remains potent, with broad geopolitical implications and requiring of Naypyitaw a delicate balancing act.

Influence on the election

China has the ability to exert its influence in other countries and elections in the region. This comes in many forms, from economic measures like buying up local media and promoting pro-Beijing businesses, to launching “fake news” campaigns on social media and espionage. Unlike Russia, China doesn’t get involved in direct electoral meddling, but the rise of Chinese influence and power projection in Myanmar, and its massive infrastructure investment in the country, have sparked a heated, and unprecedented, debate among not only the elites but also ordinary Myanmar citizens.

In the next 10 years the political and economic influence of China will only increase in Southeast Asia, highlighting the decline of US influence in the region. Myanmar must prepare to face these challenges.

China is growing more assertive in trying to influence elections in the region. For instance, in Cambodia several years ago, China took assertive and bold steps to help Hun Sen, one of Beijing’s staunchest allies in Southeast Asia, win the country’s election in 2018.

In Sri Lanka, China welcomed “old friend” Mahinda Rajapaksa’s landslide election victory in August this year and assured him of its full support, as Beijing looked to advance its strategic cooperative partnership with the island nation. Since 2015, after Rajapaksa became the president of Sri Lanka, China has substantially increased its engagement and investment there; the election victory no doubt strengthened China’s influence in the country.

A similar story can be seen in Nepal. In 2017, communist parties in Nepal with close ties to neighboring China emerged victorious in the country’s largest democratic exercise ever. China poured investment into the building of airports, highways and hydropower projects in Nepal, while Chinese diplomats have worked to increase ties with Nepali political leaders.

Anti-China sentiment

A similar pattern can be seen in Myanmar. Chinese influence is visible in the country, but equally, anti-China sentiment is strong and persistent. No political leaders—and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is no exception—want to be seen as too close to China in an election year. (In 1967, Myanmar saw anti-Chinese riots, stemming from the spread of China’s cultural revolution ideology among Chinese expatriates in Myanmar.)

Another example of this phenomenon can be seen in Indonesia, where President Joko Widodo appeared to distance himself from Beijing and downplay the importance of Chinese-funded projects in the country, when seeking re-election last year.

Overcoming the perception of being too close to China is a difficult task that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and many other Myanmar politicians face. As she has been accused of being a pro-China politician in the recent past, the State Counselor will have to walk a tightrope.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who has embraced China’s BRI projects, will also be well aware of the recent spat between the US and Chinese embassies in Yangon. It is a politically delicate, and diplomatically awkward, moment for her.

Understandably, the Myanmar government does not want to be seen taking sides in an extended tussle between China and the US amid rising geopolitical competition. On the other hand, a majority of Myanmar people have a negative view of Chinese-funded projects in the country.

November’s election will have significance for the country’s relationship with the major powers and its often-delicate geopolitical alignment with its giant neighbors, including China.

Whoever leads the next government in Naypyitaw, it would be foolish to expect an administration that is overtly pro-China, Japan, India or US. As such, we can expect Myanmar’s strictly neutral foreign policy to be maintained.

You may also like these stories:

In Myanmar’s Karen State, Ex-Insurgents Create a Haven for Chinese Casino Bosses

Sino-US War of Words in Myanmar a Test of Naypyitaw’s Allegiances

Myanmar’s Ruling NLD Must Address Its Achilles’ Heel: Choosing the Wrong People