YANGON—With more and more Chinese investment flowing into the country, many key government officials are speaking out in support of the projects, which range from a high-speed railway line to special economic zones to seaports. At several local investment forums, they have voiced the view that China’s grand infrastructure projects will bring economic development to Myanmar and economic benefits to local people, while boosting the country’s strategic importance in the region.

But what they have so far failed to mention is the possible environmental and social impacts of the projects on host communities. They rarely talk about how the projects threaten biodiversity, protected forests and natural water resources. Faced with this official silence, experts and activists worry aloud about land confiscations, influxes of migrants, loss of livelihoods and air, water and noise pollution in the project areas.

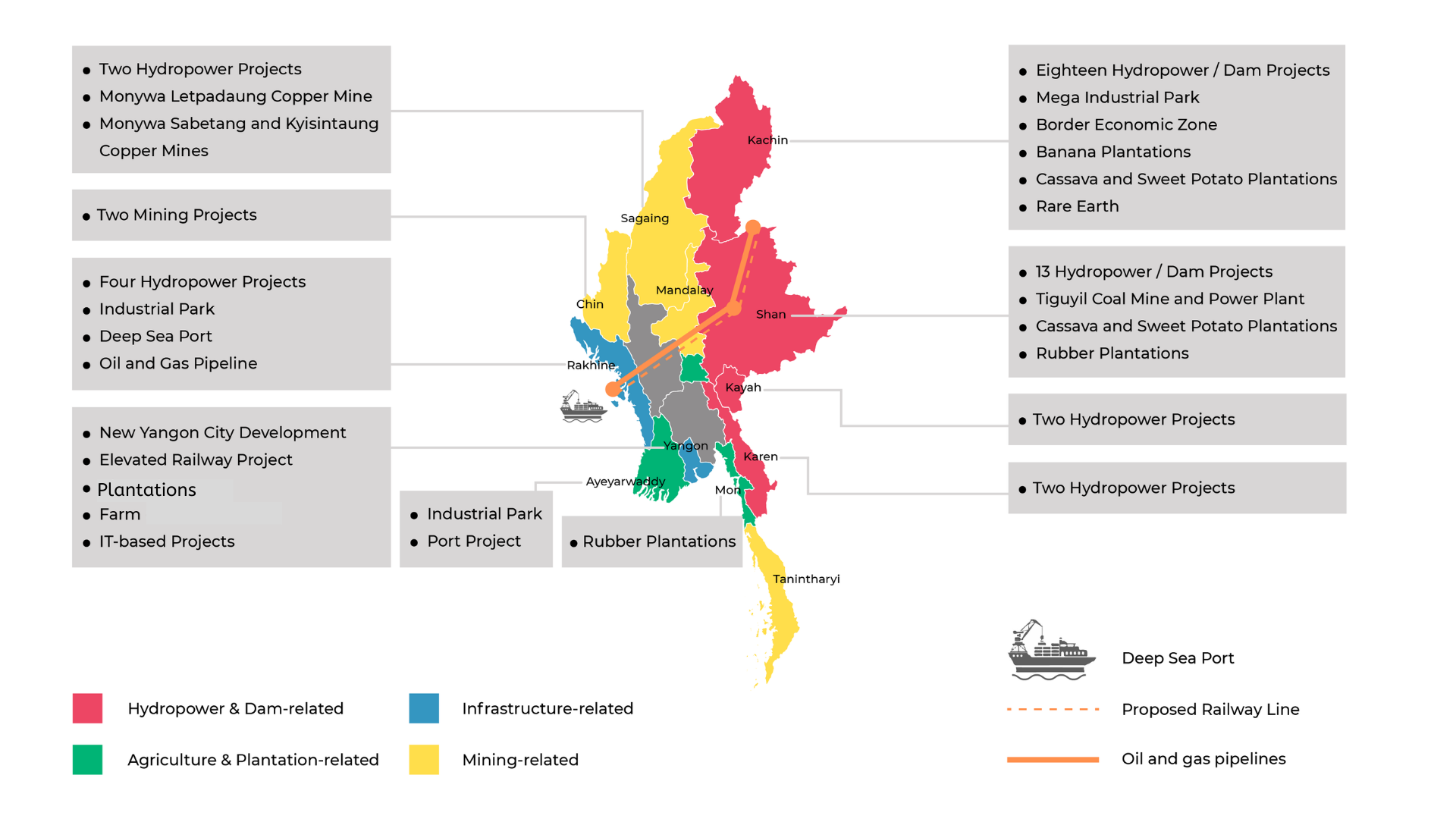

Massive project-related activities are now being implemented under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) framework in Myanmar, following the signing last year of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with China to establish the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC).

The estimated 1,700-kilometer-long, Y-shaped corridor will connect Kunming, the capital of China’s Yunnan province, to Myanmar’s major economic centers—first to Mandalay in central Myanmar, and then south to Yangon and west to the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Rakhine State. In fact, the CMEC is the initial phase of the BRI’s Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor connecting Yunnan and the Bay of Bengal.

According to Chinese academic reports, two road infrastructure projects within the BCIM Economic Corridor have been proposed for Myanmar: An east-west corridor connecting China with India and Bangladesh via Mandalay and central Myanmar; and a north-south corridor connecting the east-west corridor with the Indian Ocean via Yangon.

According to Myanmar officials, the construction of BRI backbone projects is set to begin next year. Some of them already have deadlines, particularly the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ), the Muse-Mandalay railway and three cross-border economic cooperation zones in Shan and Kachin states.

Moreover, major infrastructure projects including an economic development zone in Kachin State, an industrial zone in Mandalay Myotha Industry Park, a Chinese textile city project within Pathein Industrial City, an industrial zone in Bago, and other side projects such as roads, railways and bridge-upgrading projects in Shan, Mandalay, Naypyitaw and Rakhine’s Kyaukphyu are moving forward under the CMEC brand.

The massive scale of the project areas has prompted concerns from environmentalists, as Myanmar was ranked as one of the three countries or territories (along with Puerto Rico and Honduras) most affected by weather-related damage in the last two decades. According to the Global Climate Risk Index 2019, this is due to a combination of severe environmental vulnerability along with pre-existing social fragility and weak institutions.

“Large infrastructure projects like the BRI often have an irreversible environmental impact. If it is implemented in a forested area, it will create deforestation. This contributes to climate change in the host country. When there is climate change, natural disasters will follow,” said U Win Myo Thu, the chairperson of the Green Motherland Development Association, a leading environmental organization in Myanmar.

“Moreover, it would create unwanted social impacts. Some areas in Myanmar are environmentally, politically and socially sensitive. [Project implementation] needs to be handled carefully and must take those issues into consideration,” he said.

Given that most of these projects haven’t yet begun, the concern may seem premature. However, Myanmar’s previous experience with Chinese projects would seem to justify such worries.

Past experiences still hurt

Sad but true, in Myanmar, Chinese companies are less popular and remain controversial among locals due to their projects’ environmental and social impacts.

The Letpadaung copper mine in Sagaing Region is one major example and has become a flashpoint of public resentment toward China. Operated by China’s Wanbao Mining Company, the mine has been linked to alleged forced evictions, land grabs, the violent suppression of protests, negative environmental and health effects, and the destruction of an important religious site.

The conflict gained national prominence in 2012 when police attempted to disperse protesting villagers and monks with smoke bombs, burning several people in the process and sparking a wave of public outrage.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi chaired an investigation commission into the mine in 2015. While it did not recommend closure of the mine, the commission’s report suggested the company carry out an environmental impact assessment, a social impact assessment and a health impact assessment, or implement an environmental management plan, before the project continued.

According to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Wanbao had to carry out an EIA report to move the project forward.

However, in May 2019, the government officially expressed concern over the elevated level of particulates in the atmosphere near the Letpadaung Taung copper project, which exceeded the prescribed level. Lawmakers complained about the increased level of sulfur dioxide in the air near the factory while raising concerns about deforestation in the area.

The area offers a textbook example of the environmental degradation that can result from such projects.

Comparing aerial photos of the mine taken in 2009 and 2019 shows how the project has left the surrounding area environmentally scarred.

Move slider left and right to see the difference

The graphic compares the Letpadaung copper mine project in 2000 and 2019. It also reveals that a tributary of the Chindwin River near the project dried up in 2019.

Move slider left and right to see the difference

In a separate project, a controversial Chinese-backed nickel mine is embroiled in a longstanding dispute with villagers in northwestern Myanmar’s Sagaing Region over accusations of insufficient land compensation and environmental impacts caused by the waste byproducts from a metal-processing plant.

Operated by China’s CNMC Nickel Company Ltd. (CNICO), the Tagaung Taung plant, which sits near the boundary between Sagaing and Mandalay regions, involved the seizure of more than 3,000 acres in 2007. However, 122 local farmers told the media they were given insufficient compensation for their land (50,000 kyats per acre, or about US$33 per 0.4 hectare).

While the company’s website claims it works to ensure environmental protection, the villagers said the compensation they received failed to take into account the contamination of their fields or the coal waste that flows directly into the local waterway and nearby cultivated fields when it rains.

They said the polluted air and solid waste from the operation have affected their health, and accuse the company of discharging wastewater from the plants directly into the Irrawaddy River.

Google Earth image of the Tagaung Taung nickel mine.

The graphic shows the extent to which green areas have disappeared near the China-backed Tagaung Taung nickel mine since 2007.

Move slider left and right to see the difference

Another Chinese-backed project is the 771-km-long Sino-Myanmar oil and gas pipelines, which run in parallel from the port of Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State on the Bay of Bengal through Magwe and Mandalay regions and northern Shan State before entering China. The result of an agreement signed under the military regime in 2008, the project has been controversial since 2013, often provoking opposition from local communities and environmental organizations.

While the company’s CSR (corporate social responsibility) report claims that it follows standard environmental rules and regulations, U Ye Thein Oo, the national coordinator of the China-Myanmar Pipeline Watch Committee, a local NGO that has been monitoring environmental and social impacts across the pipeline area, told The Irrawaddy the committee found that some townships in Rakhine and Shan states and Magwe Region have suffered land erosion due to the pipelines.

The committee pointed out that the Chinese company so far doesn’t have a proper environmental management plan to alleviate the project’s environmental impacts.

Myanmar, BRI and Its Stakes

A World Wildlife Fund (WWF) report last year said that the BRI in Myanmar cuts through areas of the Irrawaddy River basin and surrounding mountainous areas that are home to around 24 million people. The people in these areas depend on their rich natural resources to survive – the forests, rivers, land and ocean – including the drinking water and shelter from natural disasters they afford.

The WWF warned that corridor projects in Myanmar, if not properly planned, could have many negative impacts—in particular landslides, flooding and water pollution in Magwe and Bago Regions as well as in Chin and Shan states—due to increased runoff of soil, sediment and other pollutants.

According to the WWF’s 2017 analysis mapping the environmental impacts of the BRI, Myanmar is in the “highly impacted” category in terms of the overall environmental impact and the “critically endangered” category for threatened species. Moreover, the analysis said 74 percent of protected areas would suffer a negative environmental impact and key biodiversity areas would be impacted the most.

The BRI is not only creating environmental risk in Myanmar but also in other member countries. A recent report by Tsinghua University’s Vivid Economics and Climateworks Foundation said that by 2050, the annual emissions of BRI countries will far exceed the target levels for complying with the Paris Climate Agreement to keep global warming below 2C.

EIA, SIA for BRI backbone projects

Environmental impact and social impact assessments for two key projects of the CMEC—the Kyaukphyu SEZ in Rakhine and the Muse-Mandalay railway project in northern Shan State and Mandalay Region— are now under way.

The nearly 415-km-long railway project is an initial part of a strategic China-Myanmar High Speed Railway, which aims to connect Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State with China’s Kunming via Muse.

The EIA for the Muse-Mandalay railway project is being carried out by Ever Green Tech Environmental Services and Training Co. Ltd based in Yangon. The company says it has held 19 public consultation meetings in the cities the railway will pass through.

The Irrawaddy has learned that according to the feasibility study, 60 tunnels, 124 bridges, 724 road crossings and 36 stations will be constructed along the railway.

Company adviser Dr. Kyaw Swar Tint told The Irrawaddy the team has discovered that some major environmental and social impacts are likely, including the loss of protected forests and watersheds, waste problems, noise and air pollution, as well as land confiscations, loss of livelihoods and other social problems caused by the massive migration that will likely be prompted by the railway project.

“Land confiscation will be the biggest problem, as most of the project areas will pass through villages and farmlands,” he said. He declined to say how many villages or how much farmland would likely be affected.

According to Dr. Kyaw Swar Tint, large areas of protected forest in the project areas would be cut down to make way for power stations, as the railway line’s 100 mph trains will be electric. He declined to say how many hectares of forest would be axed. Worse, he added, the high-speed railway would create a lot of noise and vibration, posing a threat to the beauty and nature of the Shan highlands.

Ever Green Tech also found that watersheds would be lost due to project construction. The majority of the people in Shan State rely on the area for their water resources.

“This is another very important issue for a majority of local people,” he said.

As the Sino-Myanmar oil and gas pipeline passes through Shan State, the China-Myanmar Pipeline Watch Committee has also carried out research about the railway. The committee’s national coordinator, U Ye Thein Oo, told The Irrawaddy that aside from major concerns like land-grabbing without proper compensation, the ecosystem of the area would be seriously affected.

“The project is huge. They will drill into the mountains, underlay soil for the railway track and use a lot of materials for construction. It will surely affect the ecosystem, original forest areas, water resources and farmlands, even if they use high-technology methods,” U Ye Thein Oo said.

“We have raised concerns several times during the consultation meetings. But we haven’t received a satisfactory response from them,” he added, referring to government officials from Myanma Railways and their Chinese counterparts at the project developer, China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group.

In videos of the public consultation sessions obtained by The Irrawaddy, officials from Myanma Railways urge local people to accept the project, saying it will benefit them economically.

“It would take only three hours [to get] from Muse to Mandalay. The flow of trade and people will be faster and more convenient. It will be a very beneficial project for the country,” U Htay Hlaing, Myanma Railways assistant general manager, is seen saying at a public consultation meeting in Pyin Oo Lwin, Mandalay Region, in August.

Experts also complain that the Chinese company spent just four months on the feasibility study for the railway. They say it’s less than comprehensive because it excludes some townships, which the company was unable to reach due to frequent clashes between armed groups and government troops in northern Shan State.

Another backbone project is the Kyaukphyu SEZ in Rakhine State. The project, which has a 1,000-hectare industrial park and deep seaports on Made and Yanbye islands, is designed to provide China with direct access to the Indian Ocean, allowing its oil imports to bypass the Strait of Malacca.

The 2017, Kofi Annan’s Rakhine Advisory Commission report recommended the Myanmar government conduct a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and labor assessment for the Kyaukphyu SEZ before the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) process, to find out its consequences on local communities, and its risks and benefits for other industries in the area.

The developer, China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC), has hired Canadian company HATCH to oversee the ESIA and a Preliminary Geological Survey for the seaport project in July, not including the SEZ. The results of the ESIA will be released on its official website as the study progresses, according to CITIC.

However, criticism has arisen among legal experts as to whether the developers are following the proper legal frameworks in line with Myanmar’s Environmental Law. The law states that any mega project, such as the Kyaukphyu SEZ, requires a site-wide environmental and social impact assessment. CITIC has not responded to the criticism.

In one of the few studies of the likely social impacts of the SEZ, the International Committee of Jurists (ICJ) said around 20,000 people potentially face involuntary resettlement, adding that SEZ-related displacements in 2014 included forced evictions, with many people’s right to an adequate standard of living being violated. The minimum wage employment offered in the SEZ would be insufficient to restore the livelihoods of displaced persons, it said.

Experts’ concerns on the BRI

Myanmar’s EIA procedures approved in 2015 under the Environmental Conservation Law require developers to disclose timely project information to communities and civil society groups. The procedure obliges developers to ensure that affected parties have opportunities to express their views and concerns before an EIA starts, as well as during and after the process.

However, experts said that even though the Myanmar government has instructed foreign investors to follow the country’s EIA procedures, there are loopholes in the actual reports due to a lack of environmental data and weaknesses in the technology applied, as well as the government’s rules and regulations when it comes to mitigating the negative environmental consequences.

Recently, the Transitional Institute, a Netherlands-based research and advocacy think tank, said the current legal and policy framework for regulating foreign investment in Myanmar is weak and mostly benefits companies, rather than local communities.

Stephanie Olinga-Shannon, the TNI’s planning and evaluation coordinator and Chinese foreign policy researcher, told The Irrawaddy that BRI projects, like all foreign and large-scale domestic investments, require strong regulation and a cohesive approach across national and state level governments.

“To limit the impacts of foreign investment, including BRI projects, these legal and policy frameworks will need to be improved,” she said.

A thorough assessment of individual investments, within their unique contexts, is also necessary before any project contracts are signed. This includes an assessment of the financial viability, debt burden, and environmental, social and economic impacts, as well as the impact on the conflict and peace process, she added.

Dr. Kyaw Swar Tint, the adviser at Ever Green Tech, which is carrying out the EIA for the Muse-Mandalay railway project, admitted that every project has some effect on the environment and on the public.

“We did our best according to the government’s rules and regulations. We need to wait and see whether the company will follow our suggestions,” he said.

TNI said government regulations on proper consultation processes, environmental standards, compensation and other key issues related to foreign investment are also either inadequate or non-existent.

U Win Myo Thu, the chairperson of the Green Motherland Development Association, agreed.

“Myanmar’s environmental governance is weak. Companies also fail to follow the rules and regulations. I do not see any improvement so far in terms of environmental governance and law enforcement.”

U Kyaw San Naing, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, told The Irrawaddy that BRI projects are normally approved by the Myanmar Investment Commission and relevant ministries, while his ministry is responsible for approving companies’ commitments not to harm the environment when carrying out the projects.

“Problems are mostly caused either by the companies’ failure to follow the recommendations or the weakness of the agencies carrying out the ESIA reports,” he explained.

The permanent secretary said authorities only learn about problems and conduct investigations when locals file complaints. When his ministry identifies them, he said, it can’t take action on all of them, as it lacks human resources.

“We can only investigate when locals in the project areas complain. We can’t do regular inspections, as we are undermanned.”