Myanmar is no stranger to infectious disease. Nonetheless, COVID-19 poses a serious challenge both for the government and the public. “We shall overcome,” I tell myself. And if I confine my reading to the state-run newspapers, it’s easy enough to believe that in the battle against the disease, victory is more or less at hand.

Along with the steady climb in the number of confirmed cases this month, the public’s awareness of and curiosity about the virus have surged. Many pray that Myanmar won’t experience a major outbreak like those seen in China, the US or Europe.

“If we have a serious outbreak like in the US or in Europe, we’re all going to die,” a friend of mine told me. Many in Myanmar share this bleak prediction.

Notwithstanding the propaganda and fake news forced on us every day in government newspapers and on social media, Myanmar’s poor medical facilities are indeed a problem. People are growing increasingly worried and rightfully ask, “Are we going to die?” Many in our country are asking themselves this question as they lie down to sleep each night.

In this light, I think the British—our former colonial rulers—were only acting rationally when they urged their citizens to leave Myanmar as soon as possible.

In March, we saw the news that the UK Embassy in Yangon had advised all British nationals in Myanmar to leave the country if possible, due to the potential pressures on local medical facilities from COVID-19 and the risk that flights departing the country would be canceled.

“The worldwide coronavirus outbreak is expected to put significant pressure on Myanmar’s medical facilities, and they may not be able to offer routine care,” the UK Embassy said.

It’s a valid concern. For all the amused snickering at the embassy’s statement by some Asian diplomats in Yangon, the British seemed to have the right idea.

If there were to be a major outbreak, and if emergency flights were unavailable, you wouldn’t want to find yourself locked in one of Myanmar’s poorly equipped hospital wards or quarantined in a hostel or dormitory. (Although, to be fair, some of the dormitories set up in Myanmar to house suspected COVID-19 patients are far better than many of the country’s hostels and commercial guesthouses.)

Leaving Myanmar makes sense. As opposed to Thailand, where some Western diplomats may actually be safer than they would be in their home countries or cities—especially those from London, New York, Paris or northern Italy.

Ironically, the British themselves are no strangers to infectious disease in Myanmar. When they ruled the country in the early 20th century they helped to administer vaccinations and improve sanitary, nutritional and health conditions.

When they arrived, the British took note of the high mortality rates in Myanmar (then known as Burma). Certainly, the British introduced effective, if occasionally controversial, vaccination and sanitation policies, though not without difficulties, according to Judith Richell’s book “Disease and Demography in Colonial Burma”.

However, before they could introduce Western medicines and vaccinations, the “liberating” forces had to spend a decade quelling a rebellion against their rule. It was in this period that the old, traditional Burma under the Konbaung Dynasty gave way to social disintegration under foreign rule. Myanmar’s three time-honored institutions—monarchy, monkhood and myothugyi (township chiefs)—were replaced by colonial power.

What happened then was predictable: anarchy descended. Throughout a chaotic Burma, British forces were kept busy going after “bandits” and ruthlessly suppressing an armed rebellion against foreign rule. Burma learned a lot from the British in this period, particularly the proper techniques for beheading one’s opponents, and of course the infamous “four cuts” counterinsurgency strategy. (To this day, Myanmar’s military continues to employ it, making it one of the colonial period’s most enduring legacies.)

Once the insurrection was brought under control, the colonial authorities set about conquering a new foe: infectious disease.

In the 19th and the early 20th century, plague, cholera, tuberculosis, smallpox and influenza were all major killers in Burma.

Nor did the country escape the so-called “Spanish Flu” influenza pandemic of 1918. According to Richell, little preparation was made to deal with the disease, which claimed 400,000 lives from a population of 12 to 13 million.

The impact was devastating, with urban populations, Indian soldiers and villagers all badly hit by the virus, leaving the country paralyzed.

Earlier, an outbreak of plague in 1905-06 took a devastating toll. Many assume it arrived by sea from India, which was already dealing with an epidemic of the disease.

Overwhelmed by the emergency, the colonial administration set up a “Plague Council” tasked with checking and monitoring the public, including immigrants from India.

“Ships arriving from Calcutta were examined by medical officers and put into quarantine for 10 days,” Richell writes in “Disease and Demography in Colonial Burma.” First- and second-class passengers with passports were subject to a 10-day quarantine. As the plague epidemic grew, Indians—who migrated to Burma in large numbers under British rule—were often scapegoated as spreading the disease.

Travelers within the country were required to carry “plague passports”. Large numbers of people fled the badly affected towns, leaving the colonial authorities to manage major evacuations and introduce vigorous inoculation and surveillance policies.

Local people who were used to traditional medicines and healers found themselves being asked to visit district officials and submit to British medicine. It is said that family members and wives of officials came forward to convince the local population to get inoculated.

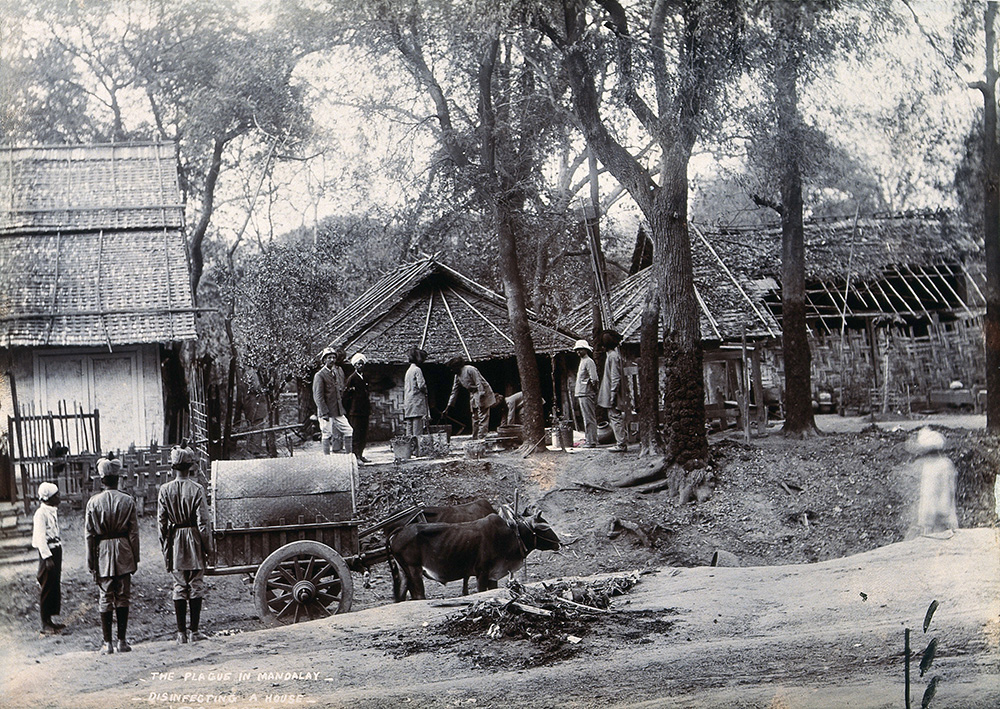

Photos taken in 1905-06 by Rangoon-based photographers Criouleansky & Marshall appearing to show colonial officials dealing competently with the bubonic plague outbreak in upper Burma, possibly in Mandalay, were published in The Graphic in June 1906.

Some scholars of the period argue that the photos are misleading, however.

In an essay on British colonial photography published in 2013, Jonathan Saha, a scholar of Myanmar history, writes, “Anti-plague measures were intrusive, contested and ineffectual. Moreover, Burma’s incorporation into British India and thus further into global trading networks probably contributed to the arrival of plague in the first place.”

He continues, “In those earlier images, Burma was initially portrayed as being liberated from a tyrannical regime, and later, as guerrilla resistance to the British intensified, as suffering at the hands of violent, degraded bandits.”

The scholar then pointedly adds, “Twenty years on and these pictures of anti-plague measures, taken in the former heartland of the now fallen Konbaung dynasty, were no doubt intended to reassure readers of The Graphic that the violent, and costly, imposition of colonial rule was worth it. If the war-time images depicted the need for an imperial order, these plague photos portrayed that newly established order functioning successfully.”

Well—we could certainly use such a reassuring imposition of order in the face of infectious disease now, as we prepare to fight COVID-19. Unfortunately, however, the British left in March.

Saha goes on to say that images of colonial officials going about their business fighting disease were intended to provide hope and create the impression that the public was in safe hands. As he puts it, the goal was to convey that “There was a rational and orderly bureaucratic response to what was a major global plague pandemic.”

Citing Richell’s study of demography in colonial Burma, Saha writes that “in 1906 almost nine thousand people died from plague in the colony. The number may in fact have been even higher given that the local population attempted to hide victims of the disease to escape the state’s intrusive anti-plague policies. When cases of plague were discovered, the sufferer’s clothes were burned, their family was segregated from the rest of the population, and their homes were chemically disinfected. Drastic as they were, these measures were ineffective in actually arresting the spread of the disease,” he argues.

But all this makes for depressing reading. So I stopped, asking myself whether the colonial period in our country had left any positive legacy at all.

Yawning, I reached for the state-run Global New Light of Myanmar, eager for more exciting news. The experience of reading state-run newspapers today isn’t much different from reading them under previous regimes, but I have faithfully kept up the habit.

Locked down and working from home, I’m sure that, like me, you’re hungry for more hopeful news—perhaps a headline like this: “Citizens Allowed to Return to Bars Next Week!”

One news headline I strayed across in the New Light of Myanmar read, “State Counselor Discusses COVID-19 Situation With Representatives of Labor and Industry”. I nodded and moved on, comforted by this and many other news items that suggested the virus situation was under control.

Other headlines and photos offered even more hope: “China Donates 20 Ventilators to Myanmar.” One photograph showed the Chinese ambassador and Myanmar officials holding up a friendship sign under the hot sun.

I couldn’t help but notice that the officials in the photo weren’t practicing social distancing, but were crowded close together—though all were wearing masks. I immediately assumed this was intended to display the solidarity and long-lasting friendship between our two nations.

In fact, the newspapers have been teeming with an onslaught of stories about China providing coronavirus aid to us—more masks, more testing kits, more this and more that. And it has gone both ways. As far back as February, the Myanmar military donated protective equipment to help China in its battle against COVID-19. This week, China sent military medical teams to numerous countries including Pakistan, Laos and Myanmar in a display of mutual trust and friendly relations, according to China’s state-run Global Times, which added, “People’s Liberation Army (PLA) medical teams are the most experienced force in China in handling public health crises.”

A colleague even told me that China and Myanmar have set up a hotline to share the latest updates on COVID-19. One highly classified preventative measure, my journalist friend told me in hushed tones on the phone, as if revealing a state secret, is to drink warm water and gurgle every day. “This advice came from a senior general in China.”

Looked at together, the staged photos that were taken in plague times in early 1900s British Burma and this week’s photos in the state-run newspapers form a historical narrative of sorts. This time, I cynically thought, the British missed a golden opportunity.

I put down the newspapers and went online to get the latest news from London. I was greeted by a headline reading: “Boris Johnson Faces Calls for Inquiry Into ‘Shocking Failures’ During UK Coronavirus Crisis”. The death toll in the UK has passed 18,000—rapidly closing in on 20,000—from over 130,000 cases.

Poor Johnson—who was himself recently hospitalized with COVID-19—was being chided for his failure to show leadership in fighting the coronavirus outbreak.

“British Prime Minister Boris Johnson on Wednesday faced a call for an inquiry into his government’s handling of the coronavirus crisis after failing to fully explain partial death data, limited testing or the lack of equipment for hospitals,” the article read.

Reading this it occurred to me that we have come a long way from the days when the British taught us not only how to handle a health crisis, but also how to spin it. This time, it seems, the British have much to learn from Myanmar—and perhaps from China.

You may also like these stories:

In Myanmar, It’s Time to Stop the Senseless War and Fight COVID-19

A Fierce Battle in Western Myanmar Has Killed Hundreds as the Country Braces for COVID

The Myanmar Govt Has Been Spared a Real Test on Coronavirus—but No One’s Luck Lasts Forever