Up until late March, fighting continued in eastern Shan State as Myanmar army soldiers and Shan insurgents clashed in remote villages. But in recent weeks the two sides have turned their attention to a new, common enemy: the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Sai Yawd Muang of the foreign affairs department of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) told The Irrawaddy that instead of fighting, “We should focus on COVID-19.”

Loi Tai Leng, the site of the RCSS’s headquarters near the Thai border, is under lockdown, as Shan leaders have ordered everyone to stay at home, he said.

For the time being, RCSS forces aren’t allowing family members from across the Thai border to visit Shan soldiers based in Loi Tai Leng. During the long holiday season, Shan migrant workers and other relatives normally return home to visit Loi Tai Leng, but this year Shan rebels aren’t allowing it.

“We told them to quarantine themselves” and “stay in bamboo huts outside,” the spokesman said.

The pandemic has also forced the postponement of a national-level political dialogue the RCSS was planning to hold in Shan State last month.

This week, RCSS leader General Yawd Serk issued a public statement asking for cooperation to prevent an outbreak in Shan State.

As a revolutionary group with scant funds, he said, the RCSS can only afford to check people’s temperatures, monitor potential COVID-19 patients and disseminate information on the disease.

Sai Yawd Muang echoed his boss’s statement, saying RCSS medical teams have traveled into the interior of Shan State to assist villagers. “We check everyone,” he said. In fact, he was talking about checking temperatures—not testing for the coronavirus itself.

In his statement, Gen. Yawd Serk briefly mentioned the Myanmar government’s efforts to contain the virus, but said that like many governments around the world, it has not been very effective yet.

The RCSS has urged Shan people to practice hand washing and social distancing, and encouraged them to wear face masks. It has also sent messages via social media to inform village headmen about the coronavirus.

In places where alcohol-based hand-sanitizing gel is not available (in many villages, it is impossible to find soap, let alone hand gel) it has advised people to use local moonshine made from rice, mixed with warm water, to wash their hands.

The RCSS has also provided locals with practical advice, such as keeping a supply of supplemental foods such as root vegetables, which are readily available in Shan State and considered healthy. Going further, it also included in its public statement instructions on how to prepare a simple traditional medicinal concoction of garlic, ginger and brown sugar, which is boiled in water and drunk.

It also cited an ancestral herbal remedy, which is to consume warm water with lime. In poor and remote villages in Shan State, such counsel from the RCSS seems sensible.

In Shan State’s Wa region, since late March, Wa authorities have banned a popular wildlife market and shut down the border with China. It is not known to what extent the Wa authorities and the Myanmar government are cooperating and sharing information on this pandemic, but some nurses from other parts of Myanmar are working in clinics and hospitals in Wa region.

Authorities in the Mong La region, also known as Special Administrative Region (4), on the Chinese border have also imposed a lockdown.

Mong La is run by the National Democratic Alliance Army-Eastern Shan State (NDAA). Mong La City is known for casinos, prostitution, drugs and nightlife.

Located in the heart of the Golden Triangle, media often portray the city as the wildlife trafficking capital of the world. Its leaders have long dismissed its reputation as a bit exaggerated, and have now shut down the business.

But NDAA leaders say they have seen an influx of unemployed people, almost overnight. The group is providing free lunches and dinners to unemployed people in the city—including those from various regions of Myanmar as well as from China—but it is not sure how long it can continue to feed them.

There has been coordination between the central government and NDAA headquarters, however.

Members of the National Reconciliation and Peace Center (NRPC) are also in touch with ethnic armed groups in order to stay updated on the situation in their respective regions. Several government officials and peace delegates are members of the NRPC.

In Kachin State, several measures have been implemented at the community level to educate people on COVID-19, and steps have been taken to quarantine those who may have been exposed. The Kachin Baptist Convention (KBC) and the Myanmar military have also cooperated to conduct medical checks and sanitation activities at the KBC’s offices and at churches in Myitkyina.

Just as the ethnic armed groups now preoccupied with COVID-19 prevention, Myanmar military commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and his officers have also made preparations to confront the contagious disease. Military officials have collectively donated over 2.245 billion kyats (US$1.6 million) to be used in the prevention, control and treatment of COVID-19.

The military has also prepared a transit center in Yangon’s Hlaing Township to quarantine 1,000 people and another site in Naypyitaw that can handle some 15,000 people.

Back in Kachin State, some residents are worried about Chinese migrants living and working there. There are rumors of Chinese patients with COVID-19 hiding in clinics and private hospitals, but local officials deny this.

The Kachin State COVID-19 Prevention Network has also been active, providing leaflets and conducting temperature screenings and health checks.

The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) is also monitoring its troops for signs of an outbreak, along with people living in KIA-controlled areas, but officers said they are in need of hand gel, soaps, masks and medical supplies.

It seems that ethnic insurgent leaders, politicians and community and religious leaders in Kachin and Shan states have been able to put aside thorny political issues and intractable armed conflicts in order to shift the focus to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

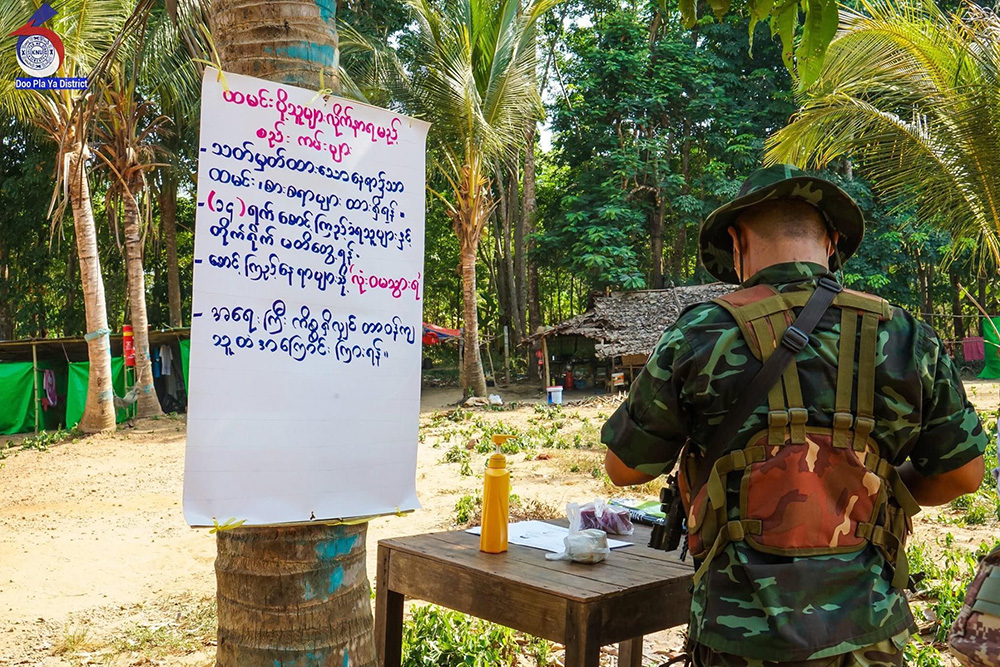

Similarly, in Karen State along the border with Thailand, Karen rebels have launched a COVID-19 education campaign to keep villagers informed by distributing leaflets. They have also set up quarantine facilities and are checking visitors and migrant workers coming back from Thailand.

But in Northern Rakhine and Chin states, bloody clashes continue between insurgents and Myanmar armed forces almost daily, and civilians continue to be killed in large numbers. Last weekend, The Irrawaddy reported on a clash in which a total of 21 villagers were killed and about two-dozen were injured when Myanmar military fighter jets opened fire on four villages in Paletwa Township in Chin State, according to local residents and relief groups.

In Paletwa, about 45 people are now in home quarantine. Many are returnees from China, Singapore and Qatar. Should patients test positive—or an outbreak occur—in the area, it is hard to imagine how health officials will be able to control the outbreak and treat patients when bullets are flying over their heads.

The situation in northern Rakhine and in Chin, where the senseless war rolls on and lives continue to be lost, is indeed depressing.

In Loi Tai Leng, Sai Yawd Muang’s message to warring parties is to put aside conflict and stop the fighting: “It is time to focus on COVID 19.”

“We check villagers every day,” he said. “We also work with NGOs.” But in the event of a serious outbreak he is well aware that there is little the RCSS or its medical teams could do to assist COVID-19 patients.

In this battle, guns, sophisticated artillery—and even jet fighters—are of little use against the fast-moving virus. Should the pandemic penetrate Myanmar’s respective ethnic regions, the revolutionary rebel forces and the country’s powerful military will be equally defenseless against it.

You may also like these stories:

Myanmar Citizens Face COVID-19 Prosecutions for Breaching Rules

Myanmar Migrant Workers Face 14-Day Quarantine on Thai Border

Rights Groups in Myanmar’s Shan State Demand Justice for Villagers