Today, in honor of the ‘88 popular uprising, The Irrawaddy digs into its archives to bring you the stories of seven heroic women and their contributions to the ’88 uprising and Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement that followed.

Of all the social and political upheavals that Myanmar has experienced since 1962, the popular uprising of 1988 is seen by many as the most prominent in the country’s modern history. Over a period of six months—reaching a peak on the auspicious day of August 8, 1988—people across Myanmar took to the streets to defy the dictatorship that had oppressed them for 26 years.

Despite an end to the struggle in a bloody military coup, young people kept the spirit of the ’88 pro-democracy movement alive—in prisons, in exile, and on borders— by defying the regime using whatever means possible. It is believed that their efforts, power and commitment made way for the elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government today.

When Myanmar marks the 29th anniversary of the uprising on Tuesday, we will honor those who dared to sacrifice their lives for the good of the country and their fellow citizens. In commemoration, The Irrawaddy chose to profile seven women who were involved in or inspired by the events of 1988, so as to represent the many more who fought alongside their male counterparts at the forefront of the democracy movement. Most of those featured below continue to be politically active in different sectors, fighting against injustice or serving people in need, and fulfilling legacies 29 years in the making.

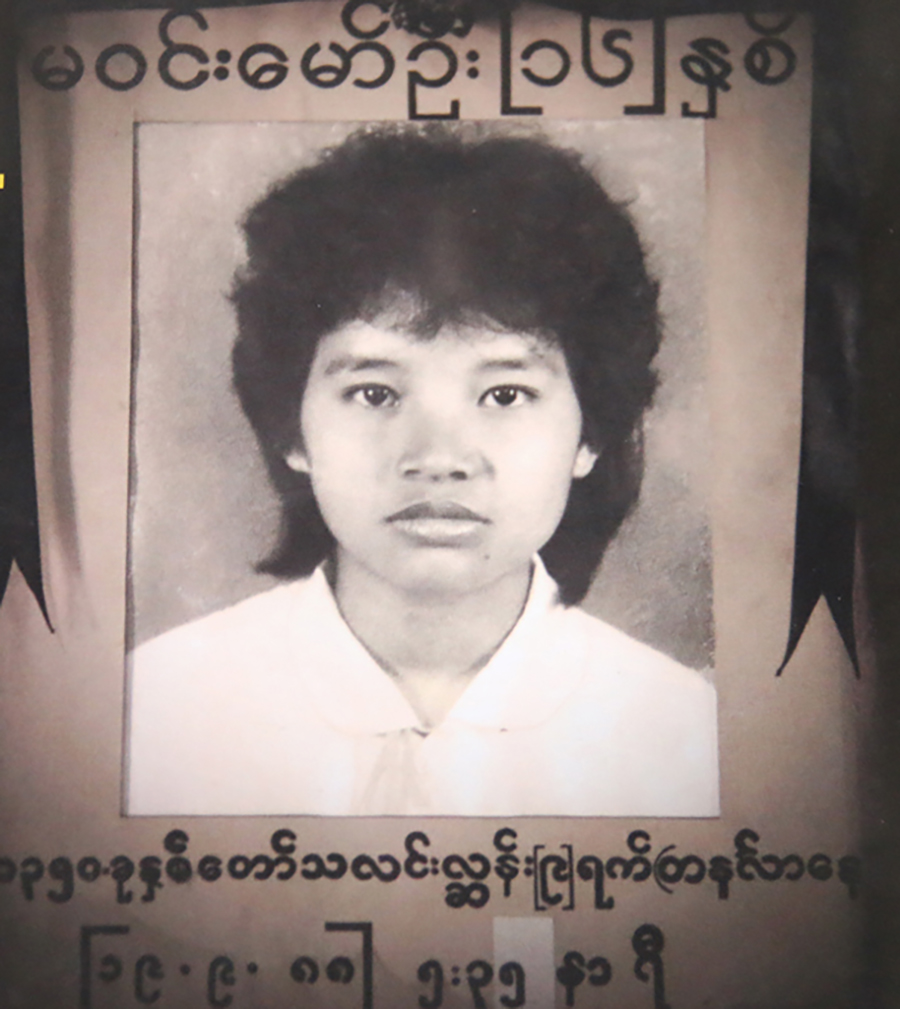

Ma Win Maw Oo: The Martyr

When Myanmar Army soldiers indiscriminately opened fire on protesters on September 19, 1988 in downtown Yangon, Ma Win Maw Oo was at the forefront of the column. Witnesses recalled that despite her bullet wounds, the high school student did not drop the picture she held of Gen Aung San until she fell to the ground. Later, her blood-soaked body was carried away by two doctors for emergency treatment, captured in an iconic photograph taken by a foreign journalist. The picture appeared in the Oct. 3, 1988 issue of Newsweek’s Asia edition, and 16-year-old Ma Win Maw Oo soon became an icon of the brutality of the crackdown, which cost her her life.

Apart from her sacrifice, Ma Win Maw Oo’s last words reflected the unbowed spirit of the participants of the ’88 uprising. In Myanmar, a deeply rooted traditional belief has it that a person’s soul cannot rest in peace until his or her name is called out by the family so that the merit of the living can be shared with the deceased. Her final request was to her father, whom she told not to perform these last rites until her country had become a democracy.

Twenty-eight years later, in May 2016, one month after the Daw Aung San Suu Kyi-led democratically elected government came to power, the last Buddhist funerary rites for Ma Win Maw Oo were performed by her family, to put her wandering soul to rest. Despite her untimely death, she will be remembered along with the other young students who put their lives before the barrels of loaded guns when they took to the streets to defy the dictatorship 29 years ago.

– By Kyaw Phyo Tha

Ma Thandar: The Lawmaker

Twenty-nine years after she took the streets to protest against the authoritarian regime, Ma Thandar finds herself sitting in the Lower House of Parliament, making laws and participating in Myanmar’s democratic transition.

In 1988, she was a leading student activist in Irrawaddy Division’s Einme Township. After a bloody military coup on Sept. 18, 1988, a warrant was issued for her arrest because of her participation in demonstrations. Ma Thandar had to flee her home and go into hiding. Later, she joined the NLD.

In 2007, she was arrested for her pro-democracy work. She was tortured during interrogations and jailed for six years in Insein Prison.

The long-time activist co-founded the Democracy and Peace Women’s Network with other female former political prisoners as a mechanism to fight for justice, women’s rights and speak out against land grabs.

Three years ago, Ma Thandar lost her husband Aung Kyaw Naing, a journalist who wrote under the name Par Gyi and who had once served as Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s bodyguard. She was in Bangkok to receive a United Nations award for her work when she learned that he had been killed by the Myanmar Army during an interrogation.

Though two soldiers initially implicated in her husband’s death were acquitted by a military tribunal, Ma Thandar’s call for answers prompted the army to make an unprecedented statement admitting the journalist had been shot in custody.

Following the 2015 election, the 48-year-old became the representative for her home region, Irrawaddy’s Einme Township, and a member of the Lower House’s Citizens’ Fundamental Rights Committee.

“We faced human rights violations and justice has never been done. But if we can protect the next generations from suffering as we did, I would see it as a success. That’s what I want,” she said.

– By San Yamin Aung

Hnin Pan Eain: The Supporter

It would have been unimaginably more difficult to survive in Myanmar’s prisons under the military regime without the moral and physical support of people like Hnin Pan Eain.

Like many other family members of political prisoners who struggled to care for their jailed loved ones, she long supported her husband, Nay Oo, who was imprisoned for eight years for his role in Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement of 1988.

Hnin Pan Eain’s preparation for this role unknowingly began in 1969, when she was just three years old, and she first visited her father in jail. He was a journalist and peace activist who was arrested by Gen Ne Win’s regime in 1966. It marked the first of hundreds of prison visits that she would make in her lifetime.

Between 1998 and 2005, the years during which her husband was jailed, she made more than 200 visits to the remote Kalay prison where he was held. The journey there was long and arduous, and allowed for just a 15-minute visitation period. She traveled 400 miles by train from Yangon to Mandalay with her five-year-old son. From there, they continued by bus for another 160 miles, through dense jungle to Kalay. Along the way, they had to cross the wild Chindwin River by boat.

After seeing her husband incarcerated in deplorable conditions, Hnin Pan Eain decided to stay in Kalay so that she would be able to make regular visits to the prison and bring him and others food, medicine and necessities every fortnight. She sold fish paste in the town market in order to survive.

She considered family visits a form of physical and mental sustenance for the political prisoners, who she saw as freedom fighters on the front line. In addition to visiting her own husband regularly, she helped family members of other political prisoners make trips to remote prisons.

In 1999, she transformed the hardship of her visits into a series of stories based on her experiences and those relayed to her by other prisoners. Originally called Daw Thandar, she wrote under a pen name—Hnin Pan Eain—under which she continues to be known.

Now a well-known 52-year-old writer, she continues helping former political prisoners and their families.

She has facilitated counseling for former political prisoners, their family members, and women in vocational schools, under the outreach programs of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, in order to heal the trauma, depression, and anxiety that haunts the past of so many who survived this era.

– By San Yamin Aung

Nan Khin Htwe Myint: The Legacy

In the same office building once run by her father, Dr. Saw Hla Tun, former head of the Karen State Council under the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), Nan Khin Htwe Myint serves as the Karen State chief minister under the NLD civilian government.

The 63-year-old has made many sacrifices due to her activism and family history of opposing military rule.

A participant in the political movement since an early age, she was detained for the first time in 1975 for taking part in the student movement. She continued to be imprisoned multiple times throughout the 1990s, including in Insein and Moulmein prisons.

She became a dedicated member of the NLD upon its formation in 1988, following the 1988 uprising. She contested and won a seat in the 1990 general election, in Hpa-an Constituency, the same constituency she represented in the 2015 general election.

Being the daughter of a politician, Nan Khin Htwe Myint fostered a homegrown knowledge of federalism, politics, and ethnic history, and fully committed herself to the movement for a democratic Union.

Her father was a supporter of the federal movements of the 1960s, in which Myanmar’s ethnic minority representatives suggested amendments to the 1947 Constitution. Later, in the 1962 military coup, AFPFL ministers and active ethnic leaders from the Shan, Kachin, Karenni, Karen and Chin communities were, among others, arrested.

Nan Khin Htwe Myint’s own family became targets for persecution under the military regime.

A strong believer that women are highly capable of coping with challenges, she has urged other women to increase their participation in politics and current affairs.

“We, as women, should never feel nor think that we are weak and cannot do things like others can. I want every woman to think that we can keep abreast of everything,” she told The Irrawaddy earlier this year.

– By Nyein Nyein

Dr. Cynthia Maung and Daw Aye Aye Mar: Those Who Bridged the Border

Often referred to as Myanmar’s own Mother Teresa, Dr. Cynthia Maung has served as a source of strength for vulnerable communities on the Thai-Myanmar border, including migrant workers and ethnic minorities displaced by civil war.

In the aftermath of the 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations, Dr. Cynthia Maung left Karen State and opened a clinic in a dirt-floor building on the outskirts of Mae Sot, on the Thai side of the border. Today the Mae Tao Clinic she founded boasts a staff of about 700 and sees between 400-500 patients each day, according to its website, treating a range of issues, from landmine injuries to facilitating safe childbirths to providing HIV counseling.

Today, Dr. Cynthia, as she is widely known, has been honored with dozens of humanitarian awards, and remains a powerful advocate for decentralized and community-based healthcare in Myanmar’s ethnic states.

The renowned ethnic Karen physician has inspired many, including Daw Aye Aye Mar, the director of the Social Action for Women (SAW) Foundation, also based in Mae Sot. Following Dr. Cynthia’s suggestion, she started with a safe house, in order to provide shelter to some of Mae Tao’s patients and orphans, and then co-founded SAW in 2001, along with other 88-generation women, including Dr. Cynthia.

The organization provides shelter and 24-hour support to orphans, domestic violence and rape survivors, as well as trafficked women and their families. SAW has helped provide in-house care to nearly 300 women and children, runs a learning center, and facilitates health awareness trainings. Some 90 orphans from SAW’s shelters receive formal education at Thai schools.

Daw Aye Aye Mar, now 48, had been involved in Myanmar’s democracy movement since 1988, and was detained in the notorious Insein Prison for one month in 1989. She left her home in March 1990 and joined the once-outlawed student army, known as the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front.

She also has had a career as a radio broadcast reporter for 19 years, with the Democratic Voice of Burma, then Radio Free Asia, and Voice of America’s Burmese service. She became particularly involved in documenting the plight of female migrant workers.

The political transition over the past five years has contributed to major funding cuts in cross-border aid and has forced many community-based groups on the Thai border to return to Myanmar. Despite financial difficulties and security challenges, migration patterns persist, and Daw Aye Aye Mar continues to provide social services to women and children, just as Mae Tao Clinic founder Dr. Cynthia continues to offer lifesaving healthcare support.

– By Nyein Nyein

Ma Phyoe Phyoe Aung: The Next Generation

Having been born in August 1988 at the height of student-led democracy movement, Ma Phyoe Phyoe Aung said she feels “close” to the struggle.

“It can’t be separated from me,” she told The Irrawaddy earlier this month, adding that it is important to remember the people’s power, unity, and struggle for democracy associated with that era. These events, she explained, helped to create her own political commitment a generation later.

Ma Phyoe Phyoe Aung was an active leader of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU) organizing committee from 2007 and until November 2016.

She was detained in June 2008 with her father U Nay Win for helping to bury the dead who were scattered after Cyclone Nargis hit the Irrawaddy Delta region in May, killing more than 140,000 people. She was imprisoned for four years after a closed trial in 2009, in which she was charged under sections 6, 7 and 505(b) of the country’s Penal Code, accused of forming an illegal organization, contacting unlawful groups and “intent to commit an offense against the State.”

Ma Phyoe Phyoe Aung faced a trial and another jail term of 13-months for her involvement in nationwide protests against the national education law in March 2015. She was released in April 2016. She remained a member of the National Network for Education Reform (NNER) and said she would continue pursuing change in the sector.

She is also a 2014 alumnus of the George W. Bush Institute’s Liberty and Leadership Forum in the United States.

As the ABFSU elected new leadership in Nov. 2016, she no longer possesses official responsibilities with the organization.

Now a mother of a five-month-old son, she is dedicating her time to her family while contributing to a youth capacity building school called the “Wings Institute,” cofounded by ABFSU colleagues. Her work focuses on peace building and reconciliation, and discussions of federalism and transitional justice.

– By Nyein Nyein