With six months left in his five-year term, Asean Secretary-General Surin Pitsuwan is making a last-ditch effort to strengthen his 260-strong staff, including 79 openly recruited from all member countries, at the Jakarta-based organisation. The success or failure of Asean integration in years to come—be it in the security/political, economic or socio-cultural pillar—will very much depend on the secretariat’s efficiency and overall capability. After all, it is central to the Asean process, and to project management and implementation, as well as other forms of connectivity. A better-equipped secretariat would make Surin’s job—and that of his successor as the chief administrative officer—in fulfilling the charter’s mandate much smoother.

The secretariat was established in 1976, 10 years after the founding of Asean, to serve as a loose coordinating office among the member countries. Indeed, it was not meant to be an effective organization that would be able to seize control of Asean’s activities and set agendas, as the foreign ministers and national Asean committees still reigned supreme.

Indeed, the position of the Asean head was titled “Secretary General of the Asean Secretariat.” Therefore, whoever served as Asean secretary-general would be the subject of ridicule because the holder was neither a “secretary” nor “general.” The job was to serve as a channel of information; in other words, running errands as a senior postman to deliver messages between capitals.

After the restructuring and expansion of Asean organs in 1992, the position of Asean chief was created to implement and follow up on the Asean Free Trade Area in the same year. Since then the international staffers, who used to be appointed or seconded, have been openly recruited based on merit. However, Asean members in practice prefer their own trusted diplomats, based on rotation in alphabetical order.

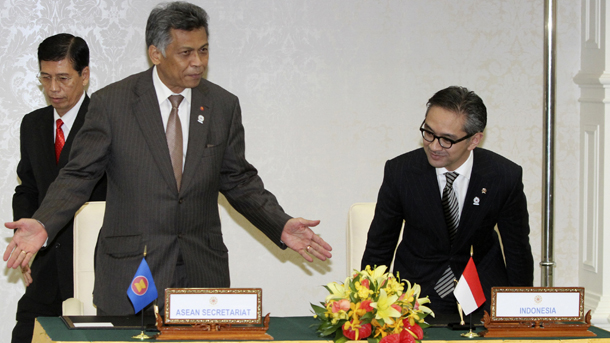

Only Surin, a former Thai foreign minister, was recruited in Thailand as the secretary-general while other member countries nominated their trusted senior officials. After the enactment of the Asean Charter in 2008, the secretariat’s administrative mandate was expanded, and so was the role of secretary-general, who could now speak on behalf of Asean.

Last year, Surin submitted a report: “Asean’s Challenge: Some reflections and recommendations on strengthening the Asean Secretariat.” He has good insights into the charter—being the first Asean chief to implement it—and what needs to be done to realize the leaders’ vision.

He argued that for Asean to meet the challenges of integrating the Southeast Asian region to create an Asean “community” of 600 million citizens, the secretary-general and his office should be given sufficient trust and latitude to carry out their responsibilities, as they run the only neutral organ in Asean.

Of course, they also need sufficient financial support, personnel and infrastructure, including modern technology. This year the secretariat has an annual budget of US $15.763 million, which translates into $1,576,300 for each member (based on equal contributions under Article 30, Paragraph 2 of the Asean Charter).

That means that, in real terms, Asean members spend less than $0.026 per person per year for operating costs in the service of community-building. In comparison, the European Union has a budget of well over 147.2 billion euros for this year.

It is worth nothing that under Surin’s leadership, the secretariat has maintained a high profile befitting the new spirit of Asean since its charter came into force at the end of 2008. Asean has been at the forefront of important international initiatives and forums.

For instance, during the post-Cyclone Nargis rehabilitation efforts in Myanmar, which lasted nearly two years, Surin and the secretariat played a pivotal role in co-ordinating both local and foreign aid workers to assist in planning and implementing plans for the devastated Irrawaddy Delta. Now, his office has been given an extra mandate by Asean leaders to take care of humanitarian efforts within the region. In the past four years, relief and rescue efforts have become a major responsibility for the secretariat.

Lest we forget, given Asean’s longstanding bureaucratic tradition, members of the Committee of Permanent Representatives (CPR), formerly known as the Standing Committee, also have a powerful role to play in accelerating or delaying programmes affecting the livelihoods of its citizens and the reputation of Asean.

The CPR is a new institution that was established by the charter. It’s still wet behind the ears, and the CPR members have now to deal with many, mainly non-diplomatic, issues, especially those involving non-state stakeholders, which they do not properly understand and are insufficiently equipped to handle.

Given the fast-changing global and regional environment, Asean as a group needs to ensure that all key policymakers—particularly the secretariat and CPR—are on the same page so that they can make timely decisions and be united in their vision. Without such a synergy, consideration and implementation of certain policies would get bogged down, due to the unintended micro-management by CPR’s members.

If history is any judge, the quality and quantity of performances of the Asean secretariat and its chief could be improved and expanded, if they are given enough space to take up issues and policies affecting the collective interest of Asean. The Asean chief should be able to use his/her reputation and network to garner support and secure funding for the common good of Asean. That helps explain why Surin set out on his very first day on the job to create the so-called “Networked Secretariat,” which can tap into the vast pool of intellectuals and local wisdom in member countries. This kind of outreach activity requires bold vision and flexibility. Therefore, the secretariat should be given additional latitude and trust, including more respect, so that its staff can carry out assigned work and policies without hindrance.

At this juncture, the Asean charter fails to clearly define the roles of these decision-makers, which sometimes leads to misunderstandings. Quite often, ambiguity rears its ugly head outside the boardroom and turns into a personal vendetta akin to a Hollywood movie. Therefore, it is important to clearly define the roles and spheres of authority of each Asean organ.

When Brunei takes up the Asean chair next year, the empowerment of the Asean secretariat should be on the summit agenda. Otherwise, it will remain a process-driven organization without much attention paid to tangible outcomes. With the Asean Community rapidly approaching, it has become a top priority that all Asean leaders need to take heed of, otherwise, the community that we envisage will never become a reality.

Kavi Chongkittavorn is assistant group editor of Nation Multimedia group in Bangkok. He has been a journalist for over two decades reporting on issues related to human rights, democracy and regionalism. The views expressed in this article are his own.