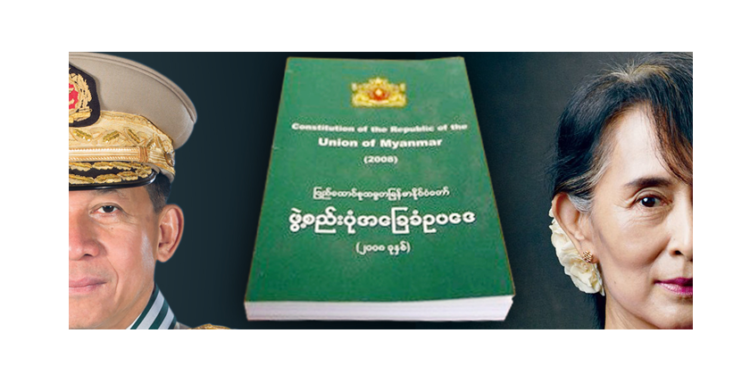

CHIANG MAI—After a heated debate in Parliament earlier this year on potential amendments to the 2008 Constitution, talk about changing the charter grew silent as politicians focused on the November election. But the silence was just temporary, and the issue has now slowly resurfaced.

The key political parties vying to win the election, including the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD), are highlighting proposed charter reforms among their policies, having kicked off their campaigns early this month.

Because changing the undemocratic Constitution is essential to Myanmar’s transition to democracy and national reconciliation, efforts at changing the charter must certainly be continued.

But what would potential charter change look like in the post-election period?

In its election manifesto, published on Sept. 1, the NLD says it aims to establish a Constitution that guarantees a genuine democratic federal union, in addition to achieving peace in the realm of ethnic affairs and establishing sustainable development and security.

The push for constitutional change has been the NLD’s longstanding, yet unattainable, goal.

Any amendment to the 2008 Constitution needs the support of more than 75 percent of lawmakers in the Parliament. And 25 percent of the seats are controlled by the military.

In March the legislators approved only four of the NLD’s 114 proposed constitutional amendments. Those merely changed Burmese-language references in three provisions and in one passage, during nine days of parliamentary votes.

Key amendments that would have reduced the special powers and privileges granted by the Constitution to the military and its chief in all branches of government were rejected by the military-appointed parliamentarians and their allied Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) lawmakers. Those two groups combined account for 31 percent of the seats in Parliament.

Citing the constitutional barrier, State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who is also NLD chairperson, urged voters to support the NLD in her Thursday campaign address. She noted the party needs 67 percent out of the 75 percent of the seats that nearly 7,000 civilian candidates are contending for in November.

Last Tuesday, USDP chairman U Than Htay addressed the possibility of making changes to some laws and specific clauses in the Constitution in his televised campaign speech on behalf of the party.

The USDP pledged that constitutional amendment is their “higher priority” and said the party’s efforts “will immediately reflect the essences of federalism, the Union, and democracy.”

The military-proxy USDP raised the possibility of changing the constitutional clause related to appointing chief ministers of regions and states. Its proposal to allow the party that has a majority in a regional or state parliament to appoint the chief minister of the regional/state government generally catches the attention of minority ethnic groups or regional/state-based smaller political parties. Hoping to win control of regional/state-based politics, the USDP has appropriated the issue.

Whether it is just for show or a sincere intention, one can look to recent history for a guide.

The USDP won a majority of seats in the Shan State parliament in 2015, but the NLD—because it won a majority in nationwide voting—had the right under the Constitution to decide the appointments of all state and regional chief ministers. The USDP enjoyed the same right during the time it ruled the country from 2010-2015 under then-President U Thein Sein.

Whether the former generals-cum-USDP leaders really care about an amendment to the Constitution that would reduce the military’s political privileges—one-fourth of legislative seats and control of the Defense, Home Affairs, and Border Affairs ministries—is an open question.

Setting aside the differences between Myanmar’s two key parties, one could ask whether amendments could be successful under any new government.

If the NLD wins a majority in the November election but still has no prospect of reducing the power of the military, the existing proposed amendments of the clauses in the 2008 Constitution, when brought up again, could end up with the same unsatisfactory results that we saw in March.

One possible way to avoid such an impasse could be focusing on charter reforms by implementing the Union Accord, which was signed by the government, military and the ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) that are signatories of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA).

State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi also highlighted the ongoing effort to amend the charter during her closing address to the last session of the Union Peace Conference on Aug. 19. She said the peace negotiators laid the foundation for a step-by-step process and implementation of the peace process beyond 2020 focusing on five processes: national reconciliation, peace, democratic transition, building a federal union and amending the 2008 Constitution.

The Union Accord is an agreement spelling out a plan for a future democratic federal union. It calls for drafting a Constitution that guarantees federal principles adopted by the peace negotiators, including the EAOs, the military and political parties.

The 10 EAOs that have signed the NCA are the Karen National Union, Restoration Council of Shan State, Arakan Liberation Party, New Mon State Party, Chin National Front, PaO National Liberation Organization, All Burma Students’ Democratic Front, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army, Karen National Liberation Army-Peace Council and Lahu Democratic Organization.

Ethnic armed groups that are currently in peace and political negotiations with the government have insisted that amending the Constitution could be done in two different ways. One is the parliamentary approach and the other is via the NCA path.

Looking back at the timeline, in fact, the NLD initially intended to try and amend the Constitution through the peace process and political dialogue based on the NCA.

But postponement of the peace negotiations following an impasse over “the package deal”—in which the Tatmadaw demanded that EAOs pledge to renounce the right to secession from the Union if negotiators wanted the right to draft state constitutions—caused discussions to derail in 2017.

In 2019, the NLD initiated its yearlong charter amendment bid in Parliament, but its efforts were rejected by the opposition USDP and the military representatives.

One of the key challenges negotiators face in discussing federal principles is the matter of state constitutions. Negotiation partners were unable to agree on that point this year.

“We have a lot of work to do, as discussions on drafting state constitutions are only beginning,” reflected Padoh Saw Taw Nee, a member of the KNU Standing Committee who has been a participant in the peace negotiations.

He reiterated the call by ethnic armed revolutionary groups that the amendment process needs to prioritize having a federally based constitution, which ensures equality and self-determination. And because of that, he said, it should start with allowing the groups to write their own ethnic state constitutions.

Charter changes would come about faster once the military representatives join hands with the EAOs and the new government to attain common federal principles that assure self-determination and equality as spelled out in the Union Accord.

You may also like these stories:

Analysis: A Win for Peace Commission as Mon, Lahu Groups Sign NCA

Will COVID-19 and Continuing Armed Clashes Combine to Postpone Myanmar’s Election?

Myanmar’s Suu Kyi Cancels First Campaign Trip as Health Minister Intervenes Over COVID-19 Concerns