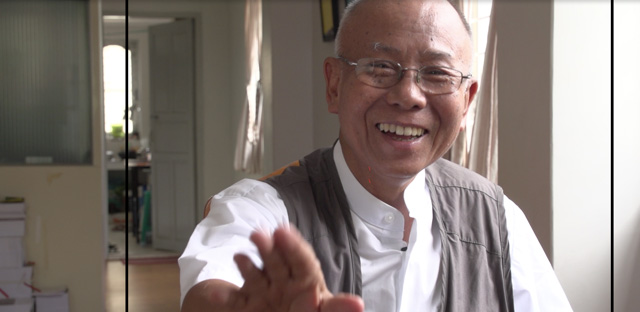

U Nay Min, the Yangon-based rights lawyer and indefatigable democracy campaigner, has died of COVID-19 aged 75.

Few people in Myanmar will know his name, particularly not Generation Z. Yet ironically, at a similar moment of revolutionary fervor, this courageous activist seized the hour as demonstrators took to the streets against the dictatorship and at a pivotal moment in his country’s history, he changed it forever.

U Nay Min came to me like a gift from God. A cub reporter, I’d been sent to Burma — as Myanmar was then known — by BBC World Service Radio on an undercover assignment in July 1988. Tensions were at boiling point and people were too afraid to talk to a foreign reporter.

Enter U Nay Min.

With a fearlessness that was his hallmark, under the noses of the country’s ubiquitous Military Intelligence agents, he sought me out at my hotel and offered to arrange clandestine interviews with dissident student leaders.

U Nay Min went further. Having consulted the astrologers for the most auspicious date, he primed the students to tell me their revolution would start at eight minutes past eight on the eighth day of the eighth month of 1988, just weeks away.

The tapes were smuggled out in British diplomatic bags, sent to BBC headquarters in London and broadcast back on the Burmese Service. Zero hour had been announced to a people desperate for change and at the appointed minute, the 1988 revolution began.

U Nay Min was the mastermind of this seminal “big bang” moment, which resonates loudly today as the Civil Disobedience Movement again braves military repression on the streets.

Unlikely spin doctor

In a time before Twitter and Facebook, U Nay Min realized the value for Burma of getting the brutality of the military into the international headlines.

In truth and with decades of hindsight, I salute his manipulation of an inexperienced reporter for the greater good.

Beyond students, U Nay Min introduced me to a disgruntled army officer who described the human rights abuses perpetrated by the military, for example using villagers in the ethnic nationalities areas to walk in front of troops as human mine detectors.

When the people of Burma heard these stories directly from a serving officer, hatred of the army grew further and international outrage against the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) also mounted.

U Nay Min was an unlikely but artful spin doctor, who understood far better than the butchers with the guns the power of the mass media to turn world opinion.

After a week I left Rangoon (now Yangon) in haste for neighboring Bangladesh on the advice of the British Embassy, who saw me as a diplomatic incident waiting to happen.

Undeterred, U Nay Min tracked me down in Dhaka and sent me news by telephone on an almost hourly basis, using the codename Eastern Star.

Journalists across the country had joined the general strike and were reporting in to him, sidestepping state control of the media. Eastern Star had become the most powerful opinion-maker in the land and used his newfound power to maximum effect.

During the twice-daily broadcasts by the BBC Burmese Service, the country came to a virtual standstill, as 44 million people hung on every word of reports that U Nay Min had fed me.

But within weeks he was arrested, given an eight-year sentence, held in solitary confinement and badly tortured. Such was his commitment to the power of truth telling, that on his release, Eastern Star called me in London to give me more information.

He was rearrested and imprisoned for another eight years.

Buddhist conviction

When I returned to Yangon in 2013 for the first time since those events, I made my peace with U Nay Min. It was hard for him. The military told him I had betrayed him to them.

He was gracious and with true Buddhist conviction confessed he must have been a bad person in a previous life.

He was at one with his past, but exasperated by the lack of political movement in the country and frustrated by the military’s decision to revoke his lawyer’s license, which thwarted his raison d’etre: protecting the vulnerable and advocating for the voiceless.

He’d devoted much of his life as a lawyer to defending Burma’s minorities, particularly the country’s Muslims, on one occasion risking his life to write a protest letter to the hated dictator, General Ne Win.

Last week, when we heard he’d contracted COVID-19, we arranged for fresh oxygen to be taken to U Nay Min’s bedside. The tank he was already using had a faulty valve and though we fixed it, the damage had been done and he passed away in the middle of the night.

My only consolation is that U Nay Min would probably have seen this as a fitting end, dying in a final act of solidarity with the most disadvantaged around him.

Rest in peace, U Nay Min. Yours was a life of sacrifice, lived for others. May your foresight, courage and commitment never be forgotten, particularly in Myanmar, a country whose fate you shaped and where your legacy lives on in Generation Z.

Eastern Star may have been extinguished, but your light still shines and always will.

Chris Gunness is Director of the London-based Myanmar Accountability Project, which fights cases in national courts for the victims of human rights abuses committed by Myanmar security forces.

You may also like these stories:

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Misses Myanmar’s Martyrs’ Day Ceremony

Myanmar’s Mausoleum Quiet as COVID-19 Mutes Martyrs’ Day