Railway history in Myanmar is a strange story. For more than a century, influential businesspeople have sought to tie Myanmar by rail to the rest of the world. Except for a brief two-year period during and right after World War II when the Japanese used prisoners of war to build the “Death Railway” between Bangkok and Rangoon (as Yangon was then known), the country’s rail system has remained isolated from the rest of the world. Myanmar has plenty of railway tracks in its lowlands, and beyond, but none cross a border. It is as if Myanmar were an island, rather than a nation sharing borders with five other countries.

An abundance of historic records show that the absence of a rail connection to the broader world is certainly not due to a lack of interest. This is particularly the case for a connection which would create a link between China and the Indian Ocean. But even after 120 years of various efforts to expand railway access from northern Shan State into China, a short link between the Chinese border (completed in 2022), and the railhead at Lashio (completed in 1901) remains unfinished. It seems that Burma’s highlands are no match for the engineers of the world, whether they came from the companies of British capitalists, the Myanmar military, or those of the People’s Republic of China.

What is the problem? Perhaps it is because whether they are from capitalist Britain, independent Myanmar, or Communist China, large capital projects like railways are planned using a “high modernist” point of view. The high modernist point of view means that people are reduced to being wage laborers for the railway, citizens of a larger nation-state, and farmers serving the global marketplaces. Myanmar’s highlands are notorious for producing small groups which avoid such discipline and subordination of labor markets or state capture, even though on the surface the modern governments label these groups as “poor” and regard their militias as weak. This is perhaps part of the reason why for the last 120 years the high modernist planners, with all their engineering skills, money, and enthusiasm have been frustrated irrespective of which high modernist flavor they bring to the task of railway construction.

Britain’s 19th-century capitalists plan big

The government of British India was the first to attempt to install the Rangoon to Kunming railway. In the late 1890s, British capitalists, intent on gaining market access to the highlands of southern China, successfully convinced British Parliament to ram through funding for the railway. The line was intended to extend from Mandalay to Kunming. The biggest challenge, it was thought, was to be in its engineering; the Gokteik Defile would require that the largest railway bridge in the world be constructed in a remote corner of a country which had been annexed by Britain only 15 years previously. The solution, which exists today as the Gokteik Viaduct, was completed in just nine months in 1900-1901 by the Pennsylvania Steel Company from America under British contract. The line was then pushed through to Lashio where it was abruptly stopped as it remains today.

The Lashio line did prove profitable for at least some capitalists. The Burma Mining Company, which was owned by the American engineer Herbert C. Hoover (later to serve as president of the United States from 1929-33) was perhaps the biggest beneficiary of the underutilized line. Hoover’s company established a short spur to the Bawdwin mines in Shan State, where generations of Chinese silver miners had packed out silver on pack-horses, discarding the bulky slag from their mines. This discarded slag was rich in lead ore which was economically shipped out via the new railway, generating a fortune for Hoover who became one of the richest engineers in the world. Hoover’s profitable use of the British-funded railway irritated British officials so much that he was served an ultimatum to either sell his mining business in Burma or become a British citizen. As for the railway and the Bawdwin mines, they would fall into disuse. The mines were closed during the Great Depression, and the railway continued to be operated as a local service line for Lashio.

World War II conquerors dream of railways

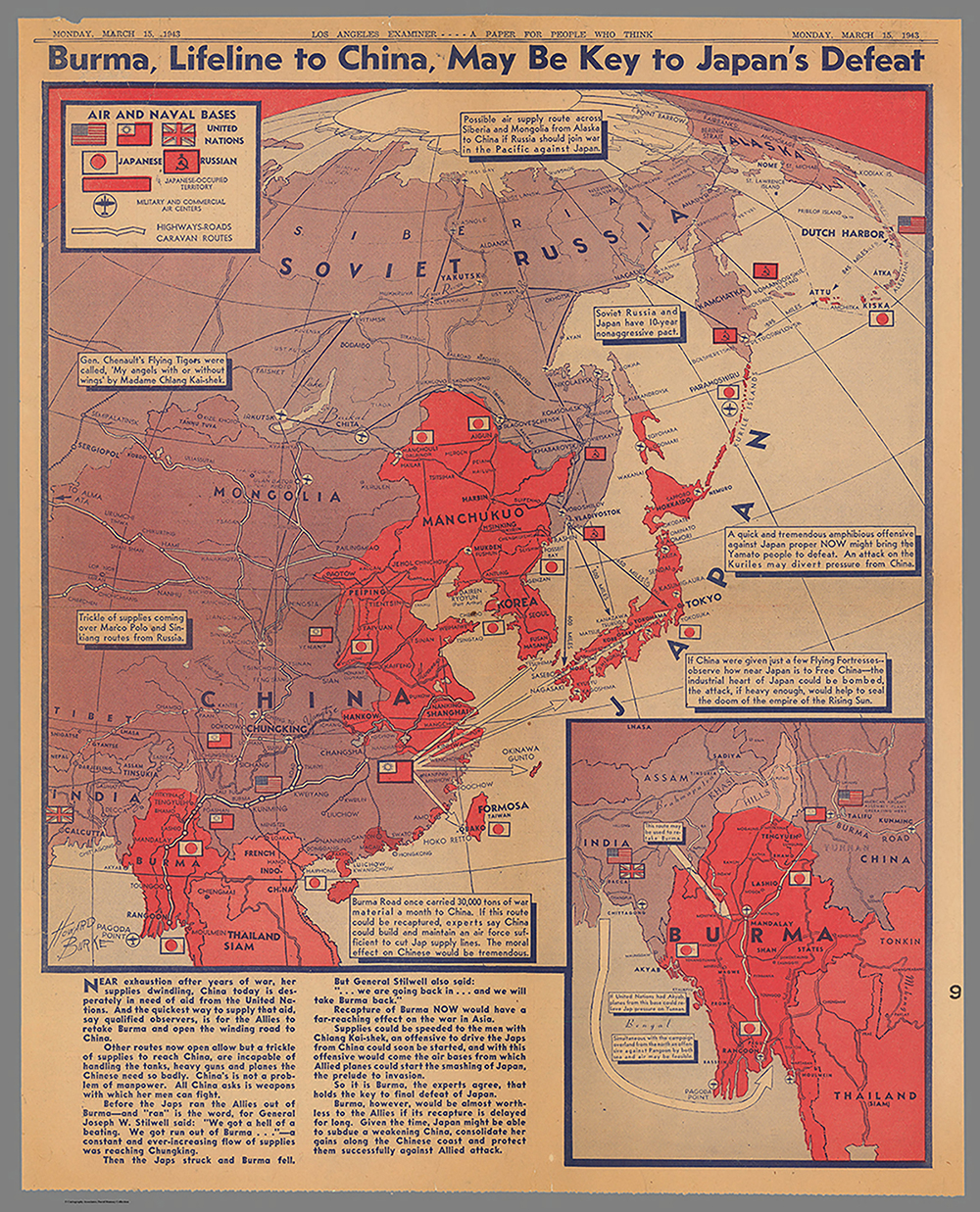

British military planners started casting their eyes northwards on the eve of World War II in the 1930s, wary of Japanese designs on China and India. Instead of a railway, the Burma Road was built in 1937-38 so the British could supply the Chinese, who were isolated by the Japanese blockade of their Pacific coast. The Japanese shut this route, and the Allies began supplying southern China with an expensive air route “over the hump” of the Himalayas of northern Burma and southern China. As victory neared for the Allies, American and British planners revived dreams of a northern railway line as a way of taking the war to southern China. But they were frustrated, too. A rough road for motor vehicles was finished, but extensions of the Burmese railway system never came to fruition. As for the rough road, even that became overgrown and unusable after World War II ended.

When the post-war independence governments of Burma looked northwards they saw Chinese threat, not opportunity. Neither the northern railway, nor other international lines were developed by the independent Burmese governments, even while new rail lines were developed in the lowlands. Further planning of a railway to southern China awaited Chinese interest, which emerged again early in the 21st century, as an economically powerful China looked outward, seeking direct access to the Indian Ocean. The Mandalay-Kunming Railway was again on the engineering drawing boards by the turn of the century. Today it is a dream for China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

21st-century Chinese plan railways, Too

From a Chinese perspective, it is well known that the Myanmar port in Kyaukphyu, Rakhine State, would give China a port on the Indian Ocean. Myanmar’s military government established a port and Special Economic Zone there in the early 2000s, and both a gas pipeline and an oil pipeline to Kunming were completed in 2013-14, permitting easier delivery of Middle Eastern gas and oil to southern China.

A planned railway that would use the same Kyaukphyu port as the pipeline has proven more difficult for the Chinese to complete, despite their engineering capacity to build an extensive network of high-speed railways in China. The railway from Kunming to Kyaukphyu port, despite extensive planning, is yet to be completed. As was the case for British capitalists and Allied military planners, the stretch in northern Burma frustrates planners. Indeed, in 2021, a high-speed rail was finally completed from Kunming to Ruili, right on the Myanmar border at Muse. Construction remains stopped there, having come face-to-face with the military dictatorship, which is again confronted by a landscape in which it cannot operate public education, schools, roads, customs or justice systems, much less a new high-speed railway sending goods to and from China. The revived military dictatorship is undoubtedly a difficult partner for the Chinese diplomats seeking secure railway rights-of-way across northern Burma.

The continuing high modernist railway dreams for northern Burma

Modernists, whether they were British capitalists, Allied militarists, or Chinese Communists have all tried to establish a rail link to southern China. As with the canceled Myitsone dam construction and disassembled Bangkok-Rangoon Railway, major infrastructure projects often remain incomplete in Myanmar’s highlands. On the one hand this may reflect a healthy skepticism of foreign-funded infrastructure that enriches capitalists like Hoover and business interests of China. Such investors are focused on generating profits for their home markets, leaving little local development in their wake.

But this reluctance to engage with international capital also perhaps reflects a more general unease with the modern institutions that railroads represent. Lowlanders and businesspeople in general see only capital and profits when they cast their eyes across northern Myanmar. This tendency seems to apply to companies from Europe, China and even Naypyitaw. But perhaps the people of northern Myanmar also see something else—a world which they are not a part of. The response to outside investment seemingly creates political conditions that make the dreams of large capital projects like railways, dams, and mines so uncertain that they are never built or completed. Inevitably this is done with the weapons of the weak, which in the case of northern Myanmar are the proliferation of polities, which from the perspective of modernizing lowlanders are “disorganized.” But together they have great capacity to frustrate the modernist ambitions of lowlanders.

The Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military), which is so unsuccessful at subduing highland militia, are again learning about those weapons of the weak the hard way, as they expand their war throughout northern Myanmar. But this is really an old lesson. The current regime and its predecessors including the British mercantile colonizers, Japanese militarists and Chinese businesses interests never seem quite able to finish the last bit of railway that connects Kunming to Kyaukphyu.

Tony Waters is a Guest Professor of Cultural Studies at Leuphana University in Germany, and formerly with Payap University Thailand, and California State University Chico. He frequently comments on Myanmar issues in The Irrawaddy, and academic journals. Email address [email protected].

David Wohlers has worked as a Civil Engineer in the United States, and has been involved with engineering education in Myanmar.

Sources

Wohlers, David C. (2022). Potential Structural Deficiencies Within the Gokteik Viaduct Railway Bridge in Upper Burma. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Engineering History and Heritage 175: 42–47.

Wohlers, David, and Tony Waters (2022). The Gokteik Viaduct: A Tale of Gentlemanly Capitalists, Unseen People, and a Bridge to Nowhere Soc. Sci. 2022, 11(10), 440; https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100440