RANGOON — A Unity journal administrative officer, who is also the nephew of the publication’s CEO, has been detained for questioning by police, the sixth Unity staff member to be held in connection with a report last week alleging the existence of a government chemical weapons factory in Burma.

Aung Win Tun was apprehended at about 8:30 on Wednesday morning while sitting at a teashop with a colleague in Rangoon, a staffer at the Unity office told The Irrawaddy.

“The SB [Special Branch police] said they would report back to the office at 12:00 [noon], but there has been no news of him until now,” the Unity representative told The Irrawaddy at 4pm on Wednesday.

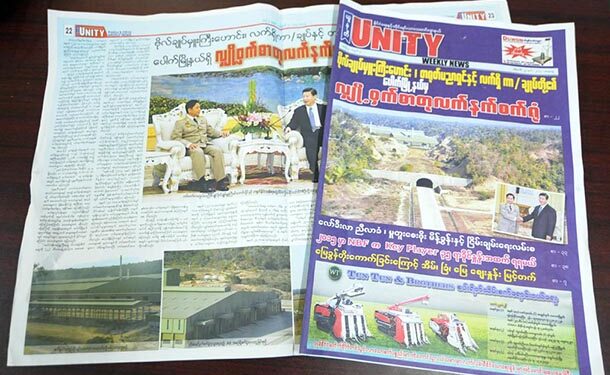

Four other Unity journalists and the publication’s CEO were detained over the weekend and charged with violating the 1923 Burma State Secrets Act after publishing a story headlined: “A secret chemical weapon factory of the former generals, Chinese technicians and the commander-in-chief at Pauk Township.” The families of the detained had the opportunity to meet with them on Tuesday.

The father of one of the journalists detained, Paing Thet Kyaw, said he met with his son in Rangoon’s Insein Prison. “My son said they are being kept well and are being held because they [authorities] still want to ask questions,” Aung Ko Lwin told The Irrawaddy.

The CEO, Tint San, and three of the journalists are being held in Insein Prison, while one Pauk Township-based journalist is being held in Magwe Division’s Pakokku Prison.

On Monday, Lwin Lwin Myint, the wife of imprisoned journalist Lu Maw Naing, was detained along with her 3-year-old daughter after being told she would be allowed to visit her husband in prison. She was held for 24 hours and interrogated by police because she had accompanied Lu Maw Naing on his reporting trip. Her phone and laptop were searched at her home and seized by the police, she said.

“They brought me to Pakokku’s juvenile court and talked with the judge to issue a remand and send me to Pakokku’s prison,” Lwin Lwin Myint told The Irrawaddy after her release.

She said she was required to sign a paper upon her release stating that she agreed to make herself available to stand trial in 14 days’ time. Lwin Lwin Myint said she was unaware of the specific charges being brought against her, but noted Section 3(1)(a)(9) on the paper she signed. The CEO and the detained journalists are also charged with violating Section 3(1)(a)(9) of the State Secrets Act.

Two friends who accompanied Lwin Lwin Myint on her visit to the prison were also held for a day and released after questioning with a pledge that they would not speak to the media. Lwin Lwin Myint, who did not have a chance to speak to her husband on Monday, said she was allowed to see him on Wednesday and said he did not complain of the treatment he was receiving from prison authorities.

“They asked me for a timeline of my life—from birth until today—and about the trip that I went on together with my husband while he was reporting. They also asked how many e-mail accounts I have and I had to tell them their passwords,” she said.

Burma’s Ministry of Information said on its website Wednesday that the Ministry of Home Affairs was “acting in accordance with the law.” The detained Unity employees are accused of “approaching, observing and checking, trespassing, entering, photographing and abetting in the factory’s restricted areas without permission,” the ministry said. It made no mention of Aung Win Tun.

The Ministry of Information on Tuesday rejected the Unity journal’s report on the chemical weapons factory as “baseless.”

Ma Thida (San Kyaung), a well-known author who is also a member of the Pen Myanmar writers’ association, questioned the relevance of the 80-year-old State Secrets Act.

“The State Secrets Act is a law from British colonial times, in 1923. When they still hold to this law, we have to reconsider whether the law is still relevant today and update and assess the weaknesses of it. … The State Secrets Act is also a barrier to free investigative reporting.”

Myint Kyaw of the Myanmar Journalist Network said authorities had not been transparent in their handling of the case. He urged the Myanmar Press Council to serve as a liaison among the President’s Office, Ministry of Home Affairs and Parliament to address the issue and take action in accordance with the law.

“We also haven’t found any damage to the government by revealing the story. There has been no big secret revealed,” Myint Kyaw told The Irrawaddy.

Ma Thida said a new press bill soon to be taken up by lawmakers lacked legal guarantees for reporters and was thus “restricting the right of the people to be informed, it’s infringing on people’s freedom of expression.”

The press bill is set to go before the Union Parliament for approval, with lawmakers still discussing stronger curbs on evidence-gathering and confiscation of media assets by authorities.

Burma’s four press associations released a joint statement comparing the detention of the journalists over the weekend to tactics carried out by the country’s previous military regime.

“We submit that holding the [Pauk] Township-based journalist first, then charging him later, and holding the CEO for more than 24 hours without pressing any charges, is behavior in the same vein of the former military regime,” said the statement from the Myanmar Journalist Union, Myanmar Journalist Network, Myanmar Writers and Journalists Association and Pen Myanmar.

The groups called on the Myanmar Press Council to negotiate between the relevant ministries, law enforcement and the Unity journal. They also used the incident to urge Burma’s press corps to report with the highest standards of accuracy and ethics.

In a statement released by the Myanmar Press Council on Tuesday, it said the “council is ready to negotiate with the authorities, as this is the part of the MPC’s role since its formation.” MPC has long said that any disputes arising between media organizations and individuals or organizations should come first to the MPC for mediation.

The MPC has not taken a side in the Unity matter, saying it would only acknowledge that “such problems tend to occur while a country is in transition, rather than commenting on which side is right or wrong.”

The Irrawaddy reporter Nyein Nyein contributed reporting.