Kachin-based environmentalists are sounding the alarm over the rapid growth of rare earth mining in conflict-affected Kachin State, fueled by high global demand for the elements, with a UK-based campaign group amplifying their concerns in a new report.

In its report released on Thursday, Global Witness revealed an alarming expansion of heavy rare earth mining in Myanmar. It said the world’s dependence on heavy rare earths from Kachin has rapidly increased and is having devastating impacts on communities and the environment.

The UK-based campaign group said Myanmar is now the single largest source of heavy rare earth elements globally. Currently in demand as part of the global energy transition, heavy rare earths are vital ingredients for permanent magnets that are used in electric vehicles and wind turbines.

In Myanmar, most rare earth mining operations are located in Kachin State and the Wa Self-Administrative Region in Shan State.

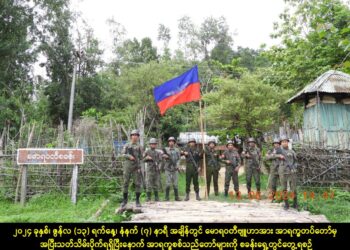

In Kachin State, the operations are centered on Myanmar military-controlled Chipwi Township in a remote northeastern corner of the state, and in Mai Ja Yang town controlled by the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in Momauk Township in the state’s southeast.

In Kachin State’s Special Region 1, controlled by militias aligned with the junta’s military, the number of mining sites increased by more than 40 percent between 2021 and 2023, according to Global Witness’s report.

“Mine workers and local community members have reported and documented numerous health issues—including two deaths attributed to chemicals used in rare earth mining,” the group said.

Two environmentalists based in Kachin State told The Irrawaddy that though there are some rare earth plots in areas close to Mai Ja Yang, the KIA stopped issuing new licenses to operate new plots in and around that area in 2023 thanks to advocacy work by environmental groups.

Many Western consumers could be unknowingly buying or using electric vehicles that contain heavy rare earths extracted from often unregulated mines in Myanmar, with a potentially devastating environmental and social footprint, according to the Global Witness report.

In its recent investigation, Global Witness found that much of Myanmar’s heavy rare earth output is used to manufacture permanent magnets, which are in demand from a range of US, European and Asian electric vehicle and wind turbine brands.

China remains the largest buyer of rare earths from Myanmar—its imports have more than doubled in the past two years. In 2021, China imported 19,500 tons (17,699 tonnes) of heavy rare earth oxides; in 2023 the amount reached 41,700 tonnes, according to the report.

“Wind power and electric vehicles have a huge role to play in combatting the climate crisis. But they cannot be allowed to fuel toxic and lawless mining. It seems that communities in Myanmar and their lands are increasingly being sacrificed to fuel the world’s hunger for heavy rare earths,” said Colin Robertson, a senior investigator at Global Witness.

Due to the massive extraction of rare earths in Chipwi without any proper environmental safeguards in place, and the excessive use of water in the mining process, landslides are frequent in the township. At least three landslides occurred in that area alone in 2023, said Kachin-based environmentalist Alice (a pseudonym used for safety reasons).

Global Witness said water sampling data revealed that streams in Kachin Special Region 1 are highly acidic and contain elevated levels of arsenic. “Pollution is threatening to lay waste to a region regarded as a global biodiversity hotspot,” it said.

According to the report, Myanmar’s lucrative trade in heavy rare earths was worth US$1.4 billion in 2023 and “risks financing conflict and destruction in a highly volatile region.” The group added that “Since the military coup in 2021, extraction has continued in the context of a ruthless dictatorship and widening civil conflict.”

According to Alice, “There have been no proper regulatory or monitoring processes implemented by a legitimate government and lawmakers since the coup. The miners and the military rulers are escalating their heavy extraction activities and that’s why the situation is now becoming very concerning.”

To operate the plots, the miners, mostly Chinese, make deals with the junta’s military and militia group leaders in Chipwi and Pang War, a town in Chipwi Township.

Environmental experts said land that has been mined for rare earths cannot be utilized for any other activities—including cultivation of any plants—for at least 17 years after mining ceases, due to possible radioactive waste created by the rare earth extraction process.

As Myanmar has no experience implementing systematic regulations concerning radioactive byproducts of rare earth extraction, environmentalists are highly concerned about the impacts of the mining projects.