RANGOON — Burmese and Chinese police cooperated last week to close down a bride matching agency of Chinese man, who illegally attempted to arrange marriages between Burmese women and Chinese men, a senior police official said.

Khin Maung Hla, deputy police superintendent of the Special Anti-Human Trafficking Police Unit in Naypyidaw, said the Chinese suspect, named Lee Pin Yee, had been distributing advertisements in Chinese border towns of Ruili and Jiegao, and in the Burmese border town of Muse, targeting Burmese women.

“Muse police found out that he came from Shweli [Ruili] and police chief Khin Maung Oo reported him to the Chinese police in Shweli. Lee Pin Yee’s office was then forced to close and Chinese police deported him to Jiangsu Province, where he came from,” he said.

“He admitted when the police questioned him that he is a matrimony agent for Chinese and foreigners, which is prohibited by Chinese government, that’s why Chinese police decided to deport him,” said Khin Maung Hla.

In China, agencies are allowed to arrange marriages between Chinese nationals and the practice is widespread.

Khin Maung Hla said a Burmese woman from Sagaing Division named Mya Mya Aye, 42, had been working as an interpreter for Lee Pin Yee for US $100 per month, adding that police had warned her to leave the area.

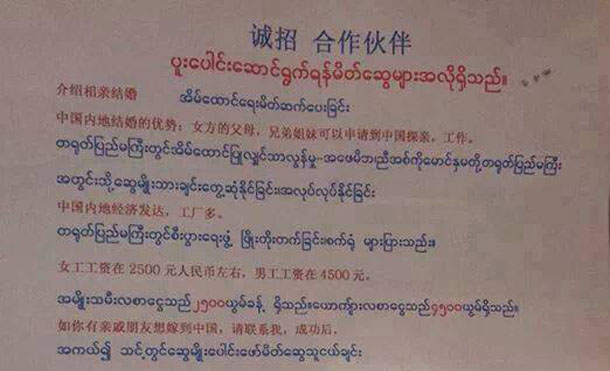

The Burmese- and Chinese-language advertising pamphlets with the headline “Partners Wanted”, tried to lure Burmese women with promises of marriages to Chinese men, who were pictured alongside new homes and cars, and with job opportunities in Chinese factories where they could supposedly earn $400 per month.

Photos of the pamphlets were circulated on Facebook and in Burmese media in recent days. “Contact me if you or your friends want to get married in China,” said the advertisement, which included Lee Pin Yen’s phone number. The women would have to pay his agency $500 once the marriage was arranged, it said.

Burmese police said such cross-border marriage-fixing operations are illegal and could lead to human trafficking of women across the border into China.

“The Chinese police said Lee Pin Yee’s attempt to get Burmese brides is unacceptable and is punishable as a human trafficking act,” said Khin Maung Hla. “Luckily, he didn’t get any client yet for his business.”

There is a strong Chinese demand for foreign wives, which is believed to result from Beijing’s one-child policy and the practice of aborting female fetuses in favor a male son. Chinese government figures released in 2012 showed the country of 1.3 billion people had about 117 men for every 100 women. By 2020, single Chinese men could number 30 million, according to the figures.

Across the border in impoverished, conflict-torn northern Burma, the proposition of marrying a well-to-do Chinese husband is an attractive one and the match-making operations have contributed to cross-border human trafficking.

The Burmese government said in a 2011 report that most human trafficking in the country is “committed solely with the intention of forcing girls and women into marriages with Chinese men.”

“Since Chinese brides are scarce and Chinese men are eager to marry … Our Burmese women become the main target for human traffickers and sorts of matchmakers like Lee Pin Yee,” said Khin Maung Hla. “Generally, the victims are young women who are poor and living in remote areas.”

The Special Anti-Human Trafficking Police Unit said it has recorded and investigated 84 trafficking cases in the first 10 months of 2013 and more than 50 Burmese women were returned home. Last year, 82 out of 120 trafficking cases handled by the unit involved attempts to bring Burmese women to China.

Although the trafficking issue remains a concern, police said the number of cases has been declining in recent years due to public awareness-raising programs by police and local and international NGOs that warn of the dangers of marriage-fixing.

“Back in 2009 and 2010, we had more than 300 cases per year, but there are only 120 cases in 2012. So, we can say that the education programs work,” said deputy superintendent Khin Maung Hla. “But I believe there are some spots where we still couldn’t reach out and we need more cooperation with citizens and civil society.”