YANGON — In April 2006, in a remote corner of Cambodia’s northern Uddor Meanchey Province, not far from Pol Pot’s dusty grave, a company run by the wife of the country’s powerful army chief landed a license to look for coal.

The following year, half way around the world, another company, Uddor Meanchey Mining Holdings, was registered in the Cayman Islands, one of the most notorious tax havens on the planet. Its sole purpose was to own the coal mine and reap the returns. Among its shareholders was the Cambodian army chief’s wife — Noup Sidara.

Her own company, Ratanak Stone Cambodia Development, was by then already exploring for iron at another site that, according to a Global Witness investigation, her husband tended to personally and was believed to own in all but name.

Sidara’s Cayman Islands shares are detailed in the Paradise Papers, a trove of 13.4 million records leaked to German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Since hitting headlines around the globe late last year, the Papers have helped shine a light into some of the darker corners of offshore finance, much of it flowing in and out of the Cayman Islands.

The secret sharer

Jutting out of the Caribbean Sea just south of Cuba, the Cayman Islands are an autonomous overseas territory of the United Kingdom, ringed by picture postcard beaches and crystal blue waters. But the sandy, sun-kissed isles are best known for a thriving — and highly secretive — financial services sector that helps the world’s wealthy avoid and evade their taxes back home.

Companies registered in the Cayman Islands pay no corporate or income tax on money earned offshore.

The Tax Justice Network ranked the Caymans third in its financial secrecy index this year, behind only Switzerland and the United States. A 2016 Oxfam report on jurisdictions facilitating “the most extreme forms of corporate tax avoidance” placed the Caymans second to Bermuda. The Guardian newspaper has called the Caymans the most notorious tax haven of them all.

“The Cayman Islands has long been one of the most damaging secrecy jurisdictions globally, playing a disproportionately large role in the international trade in financial services, and offering a range of secretive channels including anonymous company ownership,” Alex Cobham, chief executive of the UK-based Tax Justice Network, told The Irrawaddy.

“By allowing unscrupulous individuals and companies to hide their behavior from their regulators at home — including but not limited to tax authorities — secrecy jurisdictions support the evasion and avoidance of legal and social responsibilities — including but not limited to paying taxes.”

Cobham said the corporate restructuring Sidara was involved in had the potential to hide ownership in such a way that could have been used to avoid tax and obscure conflicts of interest.

Doing business offshore is not inherently illegal, and The Irrawaddy has seen no evidence that Sidara broke any laws.

But Nienke Palstra, a campaigner for anti-graft group Global Witness, said tax havens attract money launderers and tax evaders because they don’t require companies to disclose their real owners and don’t routinely share information with tax authorities and law enforcement in other countries — developing countries especially.

“Having an offshore holding company in the Cayman Islands own a Cambodian company, which is doing business in Cambodia, raises the question whether this setup has been created with the explicit purpose of obscuring the real owners of the Cambodian company,” she said.

Ties that bind

The Cambodian Commerce Ministry’s online business register names Sidara as the sole director of Ratanak Stone. But according to Global Witness, her husband — General Pol Saroeun, commander-in-chief of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces — has given the company’s operations his personal attention and was widely believed to own at least one of its mines himself.

When Global Witness investigators visited Ratanak Stone’s iron mine in Preah Vihear Province in 2005 and 2008, they found more than a dozen soldiers guarding the site. A worker told them that Saroeun himself visited in 2008 and that the soldiers stood to attention and saluted him, as they would on duty.

In a 2009 report on Cambodia’s extractive industries, Global Witness said that on both its visits “mine workers, local officials and military personnel guarding the site all said that the Ratanak Stone mine is owned by General Pol Saroeun.”

Cambodian law prohibits military personnel from managing private companies, serving as directors, using their positions “to exploit any advantage,” or spending working hours “to conduct business for private interest.”

During his visit to the mine in 2008, the general was still a deputy commander of the armed forces. He took the top job the following year.

In a report out last month, Human Rights Watch placed Saroeun at the top of Cambodia’s “Dirty Dozen,” the 12 military and police officials who have made up “the backbone of an abusive and authoritarian political regime over which an increasingly dictatorial [Prime Minister] Hun Sen rules.”

Both before and since Saroeun’s time at the top, the army has repeatedly shot protesters with impunity, violently driven families off land leased to well-connected companies and tapped into the country’s thriving illegal logging trade.

Despite careers spent in modestly paid government jobs, Human Rights Watch added, Saroeun and the rest have amassed unexplained fortunes.

Saroeun has since grown into a power player on the political scene as well. He heads a provincial working group for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and serves on its über-exclusive standing committee, in the rarified company of Hun Sen’s very closes allies. He regularly showers the premier with praise, vilifies the opposition as a fifth column that would plunge the country back into the bloody days of the Khmer Rouge if given the chance, and urges soldiers to take to Facebook to push the story along.

Under Saroeun’s watch, Hun Sen’s eldest sons have also marched up the army’s ranks in double time to senior posts.

The army chief is now set to make his political career official. He is running for a National Assembly seat in general elections scheduled for July 29. And with the CPP’s only viable rival, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), dissolved by court order last year, his victory is all but assured.

Cobham, with the Tax Justice Network, said the corporate restructuring involving his wife and the Cayman Islands raised two obvious risks for abuse — due in part to Saroeun’s political ties.

First, he said, was “the risk that the secrecy of Cayman companies could be exploited to allow the non-declaration of ownership for purposes of evading or avoiding income and/or capital gains tax, to the extent these existed in Cambodia in the period in question.”

“Second, given the powerful political connections involved, there would have been a clear risk that the secrecy of Cayman companies could be exploited to allow the non-declaration of ownership for purposes of hiding conflicts of interest in respect of government decisions affecting the businesses in question.”

The restructuring itself is not proof that the couple used the setup to avoid tax or hide any conflicts of interest.

“But the intention to create a more opaque, more complex and presumably more expensive ownership structure, with no obvious benefits but clear risks of abuse, must raise questions of judgment,” Cobham said.

A tangled web

The Paradise Papers reveal that Uddor Meanchey Mining was set up in the Cayman Islands to play a key role in what could have been a multimillion dollar project to turn Sidara’s coal mine into the main supplier of a planned power plant that would sell electricity to Cambodia, Thailand and back to the mine to keep it running.

The leaked records, reviewed by The Irrawaddy, include emails and documents ranging from share purchase and transfer agreements to certificates of incorporation, directors resolutions, legal opinions, checklists, client lists and invoices — all prepared by or shared with the offshore law firm Appleby.

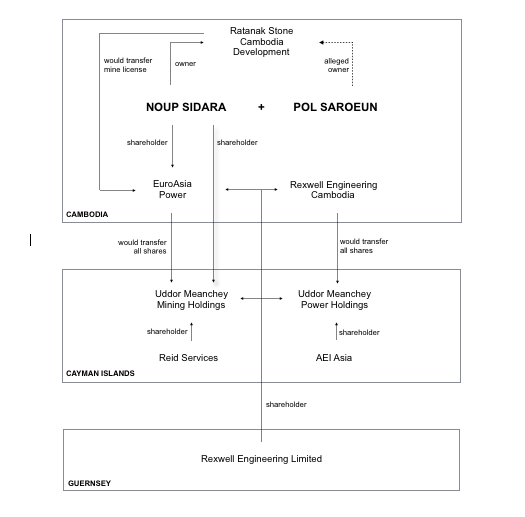

According to the records, a joint development agreement setting the project in motion was struck in June 2007. The partners included two Cambodian companies, EuroAsia Power and Rexwell Engineering Cambodia; another Caymans firm, AEI Asia; and Rexwell Engineering Limited, registered in Guernsey, a British crown dependency in the English Channel with its own reputation as a tax haven. Appleby was AEI’s legal counsel.

The plans called for Sidara to transfer the license for her coal mine to EuroAsia Power, which she also held shares in, according to the Cambodian Commerce Ministry’s business register. EuroAsia Power would then dig up and ship the coal to a 2,400-MW power plant to be built, owned and operated by Rexwell Engineering Cambodia near the mine.

The two Cambodian companies would operate as subsidiaries of holding companies set up in the Cayman Islands.

The plan was to have all shares in EuroAsia Power transferred to Uddor Meanchey Mining. All shares in Rexwell Engineering Cambodia would be transferred to another company also registered in the Caymans, Uddor Meanchey Power Holdings. Together, the two offshore companies would own the mine and plant.

Among the directors both Uddor Meanchey holding companies appointed was the affiliate of another Guernsey firm, the Sarnia Management Corporation.

On its website, Sarnia Management offers to help “wealthy individuals and their families with flexible and bespoke approaches to protect and manage their assets” with the aid of “jurisdictions and relationships all around the world.” The 2016 Panama Papers, an earlier leak of offshore financial records, named Sarnia Management as an intermediary for more than 200 offshore companies, many of them registered in Niue, a pebble of an island state in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with — like the Caymans — zero tax on offshore earnings.

The records don’t say how much the project partners expected the coal mine and power plant to cost, let alone earn. But they budgeted nearly $10 million for advisors on the power plant alone.

It appears their grand plans soon fell apart, however. In June 2008, only a year after the joint development agreement was signed, AEI Asia told its partners it would be terminating the deal.

But the two offshore holding companies lived on a while longer. Uddor Meanchey Mining, the one Sidara owned shares in, was dissolved only in 2012, five years after it was registered in the Caymans. Rexwell Engineering Limited was dissolved the same year in Guernsey, and AEI Asia appears to have been wound down as well.

Rexwell Engineering Cambodia and EuroAsia Power no longer appear on the Cambodian Commerce Ministry’s business register.

Past is prologue

Sidara declined to answer questions for this story over the phone. She said she would only speak in person but ignored offers to meet with a reporter in Phnom Penh. Requests for comment sent to the email accounts of four of her companies, including Ratanak Stone, went unanswered.

Reached by phone, Saroeun said the coal and iron mines were both taken over by Chinese companies about 10 years ago and that he knew nothing more about Ratanak Stone’s business operations. When asked about his reported role in the iron mine, and his wife’s shares in a Cayman Islands holding company, he hung up.

Cambodia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy refused to answer any questions about Ratanak Stone’s operations, past or present. “We think it’s not important for us to answer,” a ministry spokesman said.

Appleby’s Cayman Islands office and employees of the firm involved in setting up the two holding companies did not respond to requests for comment. In a public statement reacting to international coverage of the Paradise Papers in October, Appleby said it had investigated the allegations of bad behavior and found no evidence of wrongdoing either by itself or its clients.

But Cambodia has been here before. The Paradise Papers are not the country’s first brush with leaked records tying its elite to offshore companies.

The Panama Papers revealed that in 2007 Cambodia’s justice minister, Ang Vong Vathana, bought shares in RCD International Limited, a company registered in the British Virgin Islands earlier that year and dissolved in 2010.

Responding to the revelation in a statement in 2016, the Justice Ministry denied that Vong Vathana had bought the shares and said the minister had never even heard of RCD. It called the information “fake news” and said the minister would take legal action.

There was no investigation into the offshore investment and Vong Vathana — a member of the CPP’s central committee — remains Cambodia’s justice minister, presiding over a court system widely seen to be in thrall to the ruling party.

But the Panama Papers did spark investigations into thousands of individuals and companies for possible tax avoidance or evasion by other governments around the world, even pushing some leaders and top officials out of office. In Iceland, Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson resigned soon after the leaks revealed that he and his wife owned a company in the British Virgin Islands set up to hold their investments. In Pakistan, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif stepped down after the leaks linked his children to offshore companies used to buy up pricy property in London; the country’s anti-graft court recently handed him a 10-year prison sentence for corruption.

The Paradise Papers have also made a mark.

Since the new leaks started making international news in November, the European Parliament has established a special committee to investigate tax avoidance and evasion. In the UK, a parliamentary subcommittee has done the same. India’s top tax authority has asked investigators to review the tax returns of some 700 nationals named in the Papers, from movie stars to ministers.

Palstra, with Global Witness, said Saroeun and Sidara should be due their own investigation, given the general’s possible beneficial ownership of the iron mine, his senior position in the Cambodian regime, and his wife’s business interests in a prominent tax haven.

“All of these factors present greater risk of potential wrongdoing and should be subject to greater scrutiny for that reason,” she said.

“There’s clear ground for investigation,” agreed former CNRP lawmaker Mu Sochua, all the more so now that Saroeun was set to take public office. “But it has to be an independent investigation and with expertise.”

In 2010 the Cambodian government set up the Anti-Corruption Unit (ACU) to pursue wayward officials. It holds their sealed asset declarations and has discretion to open them when it suspects wrongdoing. But like most of Cambodia’s state institutions, it has gained a reputation for harassing the government’s critics while giving its allies a pass. Sochua did not expect it to be much help.

“I wouldn’t count on [the] ACU picking up this case as it would damage the name of the government,” she said.

Taxing times

Cambodia’s prime minister and his top lieutenants, long accused of running one of the most corrupt regimes in the region, show no sign of going anywhere. Over more than 30 years in power, they have learned to wield the government like a weapon, adding, amending and applying laws as needed to cut the legs off their rivals.

It’s a battle they have mostly fought and won of late not with bullets so much as bureaucracy. And if anything, they’re digging in.

During an unusually tough crackdown on Cambodia’s free press last year, the government accused several independent news outlets of, among other things, dodging their taxes.

More than a dozen radio broadcasters were driven off the air. The Cambodia Daily, after 24 years of tough reporting on the government, published its last issue in September after balking at an unaudited bill for $6.3 million in back taxes it was told to pay in 30 days or have its assets seized (the author was a reporter for the paper at the time). Hun Sen personally labeled the Daily a “thief.”

In May, Cambodia’s only other independent English-language daily, the Phnom Penh Post, was sold off to the Malaysian owner of a public relations firm that has done work on Hun Sen’s behalf. The Post reported that a $3.9 million tax bill it owed the government was settled as part of the sale.

The news media purge started about a year out from this month’s general elections, and just as the government was hammering the final nails in the coffin of the ruling party’s main opponent, the CNRP. Acting on a government complaint that the opposition party was plotting a “color revolution” with a helping hand from the United States, the Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP in November. The party and its supporters deny the claim and say the case was politically motivated.

The party’s then-president, Kem Sokha, was arrested in September for alleged treason and remains in jail awaiting trial. Many of the CNRP’s other leaders have fled the country fearing their own arrests.

In February, reacting to what it called the government’s escalating “anti-democratic behavior,” the US announced plans to pull a number of aid programs in Cambodia. A National Security Council spokesperson told the Associated Press that the US was targeting agencies it held responsible for the crackdown, including the Tax Department for opening what it called politically motivated investigations into independent news outlets.

Graft is endemic. A perennial laggard on Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, Cambodia currently ranks 161st out of 180 countries. In all of Asia, only Afghanistan and North Korea do worse.

Inequality also remains stubbornly high. GDP growth is strong, tax revenues are up and poverty rates are down. But most of those who have climbed out of penury have escaped only just; economists warn that even a minor shock could wipe out years of progress.

And in one of the poorest countries in the region, the number of Cambodians worth $30 million or more nearly tripled to 54 in the decade leading up to 2014 and was likely to climb to 84 in another 10 years, according to international property consultancy Knight Frank. It predicted that the number of Cambodians worth at least $100 million would also jump from 16 to 25.

Trade winds of change

Secretive tax havens like the Cayman Islands do more than help the rich squirrel away their wealth. They short-change countries of the tax dollars they use to build roads, schools and hospitals.

Reacting to the Panama Papers, more than 300 economists signed an open letter telling world leaders that tax havens “serve no useful economic purpose” but widen wealth gaps and hurt poor countries the most.

“As the Panama Papers and other recent exposés have revealed, the secrecy provided by tax havens fuels corruption and undermines countries’ ability to collect their fair share of taxes,” they said. “While all countries are hit by tax dodging, poor countries are proportionately the biggest losers, missing out on at least $170 billion of taxes annually as a result.”

The Tax Justice Network believes it could be even more. Using a method pioneered by the International Monetary Fund, it estimates that tax havens likely contribute to some $200 billion in lost corporate tax revenues by low-income countries and $500 billion worldwide.

Anthony Galliano, CEO of the Cambodian Investment Management Group and an expert on the country’s tax regime, said Cambodians were as likely to set up holding companies in offshore tax havens as anyone else and called them a “pretty normal and sensible structure.”

He said Cambodian-registered companies have to pay tax on profits at Cambodia’s rates whether owned from offshore or not. The advantage of going offshore, he said, is that the holding company can sell the Cambodian business it owns to another offshore company without having to pay any capital gains tax.

Galliano said Cambodia was also now enforcing transfer pricing — a practice transnational businesses can exploit to avoid tax — which should make it hard for local subsidiaries to shift profits offshore, at least in theory.

But their critics want tax havens gone. At the very least, they want their business registers out in the open and to name each company’s ultimate beneficial owners.

Cobham said the UK has done just that with its register and that EU legislation demanding the same of its members was now coming into force. In May the UK Parliament also passed a law requiring its overseas territories — including the Cayman Islands — to establish public registers by 2020.

“The territories are considering a legal challenge,” Cobham said. “But the wider message is clear: This type of anonymous ownership, so often linked to tax abuse and corruption, is living on borrowed time.”