Veteran democracy activist Ko Mya Aye, a former 88 Generation student leader and now a leader of the political organization Federal Democratic Force, was among the first people to have their homes surrounded and to be detained at gunpoint during the military coup on Feb. 1, 2021. He was jailed by the junta and only released in a mass amnesty in November 2022. The democracy activist had already been jailed on two earlier occasions by former military juntas for his political activism after the 1988 uprising.

The Irrawaddy recently talked with him to get his views on the current situation in the country more than two years after the coup attempt, as well as on federalism and the junta’s use of jailed leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to conduct hostage diplomacy.

What do you think of the junta-arranged meeting between Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Thai Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai? Do you see it as the junta’s attempt to reduce the pressure on it, both internal and external?

There has been much debate over Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s words [at the meeting] and this has had a great impact. But I think it is still difficult to know whether this statement [Don’s statement claiming that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi called for negotiations with the junta] is true [truly reflects her words] or not. Politics depends on principles and the stands that we take. It can’t depend solely on one person. We need to weigh everything against our principles and our stand to find the right path. In politics, there can be a lot of different opinions, agreements and disagreements. We need to take those into consideration but based on what we hope for, and what path we are taking. That’s how I measure it.

Another factor is that the situation has become one of political stagnation. If we look to the military side, as we all know, according to the 2008 Constitution, if two years have passed [since the emergency declaration], the election must be held. But given the current situation inside the country, there is no way it can be held. As you can see, there is no stability in many areas such as Magwe, Sagaing, Karenni [Kayah], and Karen, and thus it is impossible to hold an election. Similarly, if we look at the forces on our side, we see that it is still quite difficult to reach our original goal. This means that the situation is now in a deadlock. In this kind of situation, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s returning to the political spotlight is particularly significant. Thus, there are some who hope that this can ease the current situation. However, whether good things can happen for the country or not depends on many things. To put it bluntly, there are ways that young people are now engaged in [armed resistance] and there may be other ways. I think it will depend on which method satisfies the public’s wishes.

How do you see the role of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who was elected by the people? Is she still relevant? There are some who no longer consider her to be central to Myanmar politics. What do you think?

I would say I disagree with that. I always say that there may be differences of opinion. Not only with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi—with whomever it may be. But based on disagreements [with her], to say she is no longer central would be a somewhat biased assessment. One thing that is certain is that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is a leader who is still accepted by the majority of people in Myanmar. One can’t say the public, who see her as ‘Amay Suu’ [Mother Suu] no longer have affection towards her or accept her because they disapprove or dislike one action by her. If one thinks only they are right, and that those who are not the same as them are wrong, one is limiting oneself. Another issue is whether Daw Suu can solve the situation alone.

Today’s problem has become a federal democracy problem. In other words, we have higher political aspirations than before. This means that we can’t solve the problem without the ethnic forces. The reason for not being able to do so can be seen by looking back at the peace efforts during the U Thein Sein government in 2010. You can see the efforts of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD [National League for Democracy] government, which tried to end the civil war in the country by holding the second Panglong conference in 2015. Today’s youth strongly want to see democracy in the country and to secure the original rights of ethnic groups. When it comes to achieving those, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi alone can’t solve the problem. This is also obvious if we look at the disputes with ethnic groups that happened in 2015 to 2020 [roughly the term of the NLD government].

While Daw Aung San Suu Kyi alone can’t solve the problems, on the other hand, you have said that she and the NLD can’t be removed from Myanmar politics. Is this still your view?

I will speak openly. Now, if we held an election like before, the NLD would definitely win again. This is what the public chose. We can’t just disregard this fact. However, we can’t assume that this alone would solve all of the country’s problems. Because the current issue is no longer democracy alone. The situation has developed. In 1988, we talked about democracy. There was no [talk about] federalism. And before that, we were fed propaganda that federalism led to divisions within the Union. Gradually, it was understood that federalism needed to be established to restore the original rights of ethnic groups. The young people of the current age know better. So, if we are going to solve these issues, we can’t leave out the ethnic groups. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD’s role is important, and the role of ethnic groups is also very important.

Looking at the state of the country, how do you assess the current conflict situation?

The situation is pretty bad. If you look at politics, society or the economy, or just look at education, we are in a very chaotic situation. Things have really deteriorated. We don’t know where justice has gone with all the bloodshed and everything. Right now, I see that the country is pretty torn up. My personal view is that it’s a failed state. It is definitely a failed state. This is not a good situation. How do we recover from such a situation? There are various ways. However, one thing is certain, if you can offer a way that reflects the expectations and political aspirations of the people in the country, people will accept it. If that is the case, I believe the country will recover.

What do you think is the root cause of all these problems?

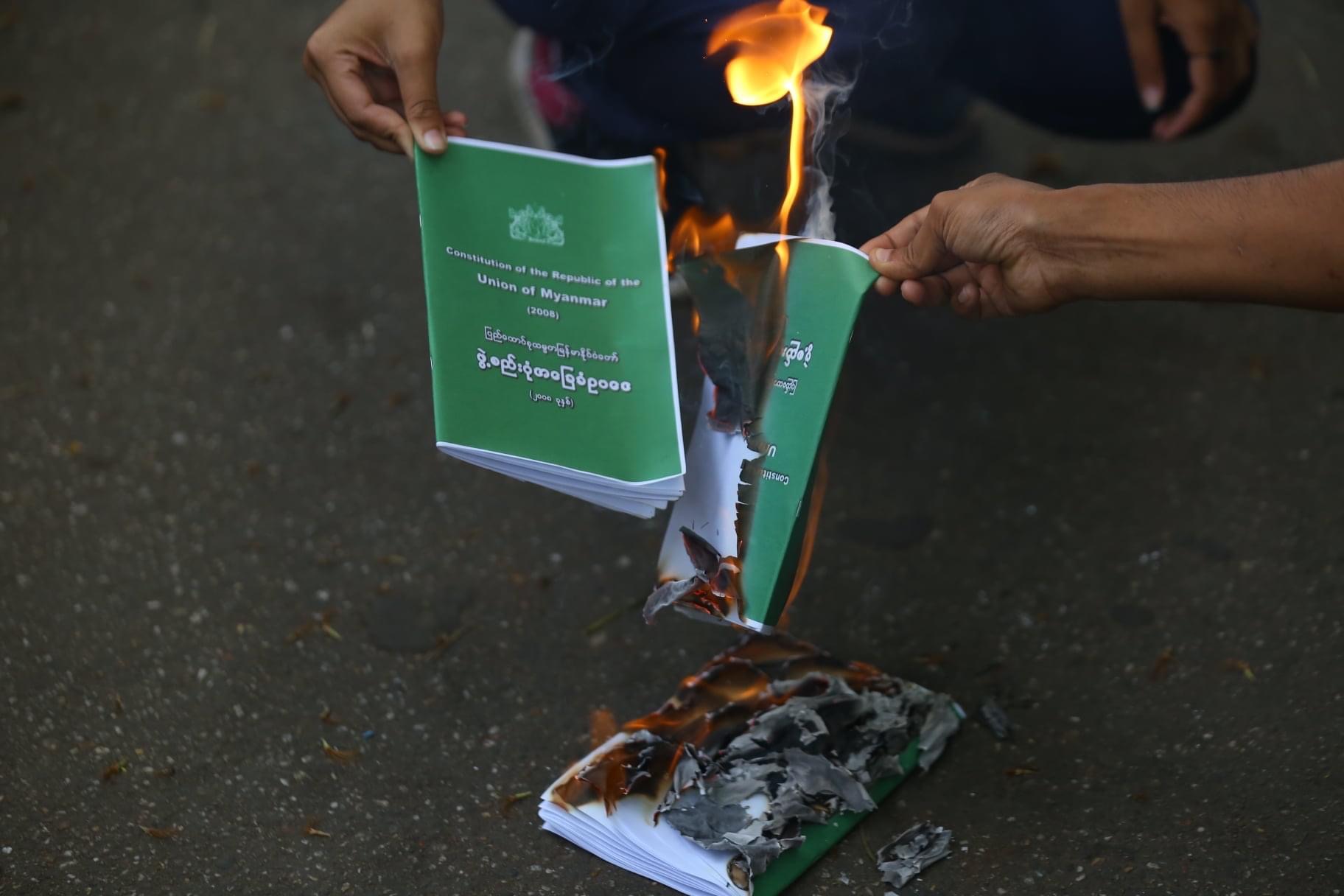

For now we are focusing on democracy and federalism. For federalism, as this is about nation building, we have to start thinking about what systems should be applied, and how. When thinking about solving the issue of federal democracy, we need to examine whether or not the 2008 Constitution encourages it. I have repeatedly said that in my own opinion, the 2008 Constitution is less oriented towards federal democracy. I do not think it can work and I want to create a new constitution that is compatible with federal democracy. There are two roads we can take here. Some may prefer to gradually expand the 2008 [Constitution]. But for me, I’d go for drafting a new one. Because we have to think about the form of the state. What are the aspirations of the ethnic groups? There are different demands and different wishes among ethnic organizations and ethnic groups. We must gather all of these first and then start thinking about how to build a Union. But there may also be those who seek to amend almost all parts of the 2008 Constitution. If we can see the light from within the darkness, the path will become clearer.

Next week marks one year since the junta’s execution of your comrade, Ko Jimmy, and three others. In light of their hangings, how do you assess the political situation in Myanmar?

On the 23rd [of July] it will be a year since my friend Jimmy and my younger brother Zeya Thaw were hanged. Since I was freed from prison, I have said that [hanging them] was committing a huge mistake. In the history of our student movement, it was the first time this happened since Salai Ko Tin Maung Oo [in 1976]… It is very ugly. The political impact is also very big. Ridiculous. It is totally unacceptable. One thing is for sure: They are noble martyrs. But their lives cannot be returned. It is a big loss for the country. A great loss for our generation and future generations.

Do you see any way out of the current deadlock?

I think it’s a little early to say. Because politics is deadlocked now and every word is very sensitive. For me, I stand on three points. No. 1 is the emergence of a political landscape compatible with federal democracy or a federal democratic constitution. No. 2, we want international cooperation to help make that happen. No. 3: How much time will it take for us to rebuild the country? For that, I don’t want it to take more than three years, as our people and country have suffered more than enough. But I have no say in deciding that [time frame]. For international cooperation, I believe that it is necessary for the international community to step in and solve it. I think it’s not easy. To be clear, we need a referee. That’s all. I approach every problem on the basis of those three things.

When it comes to international cooperation, what do you think of the international response to the Myanmar situation over the past more than two years?

There are some people who approach it with the idea that the international community will come and save us. In reality, in our own country’s affairs, I see domestic politics is more important. The international community will support, help, cooperate, and act as they can. It will not be much, as we expected. We can say to the international community that nothing has been implemented regarding the ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] Five Point Consensus for more than two years, but the international community said the same thing at the recent ASEAN meeting. If you look at the UN, the US, China, we see that they all back this Five Point Consensus. This is the international scene. We need to be aware of it.

Regarding the ethnic groups, how do you view the current situation? Some groups are fighting together with the resistance while others are engaging with the junta?

The ethnic groups are fighting for their original rights because those have been extinguished. The history of each group, the status of their region, their political ambitions won’t all be the same. And thus, they will consider [the situation] based on who can fulfill their goals and to what extent. Because [it has happened] many times in history—there was the 1947 Panglong contract, but the Panglong contract did not materialize. Similarly, before, [governments] also held a lot of discussions and things. But the desires of the ethnic people weren’t fulfilled. So they have great doubts about local politicians and local forces. We need to understand this. The interests of each group are different. And thus, there are those that are engaging with the junta. We can’t blame them for that. We just have to think about how we can bring them together. We can’t look down on them because they go to the other side and not come to our side. That won’t bring any benefits for us. When building a country, we cannot exclude any ethnic parties, including ethnic armed organizations. I think we need to try to understand this.

When building a federal democracy, is it necessary to make democratic standards such as election results a lower priority, and prioritize federalism?

Election results and federalism are two totally separate issues. The issue of nation building is [related to federalism], while elections have to do with democracy and with people voting. I see your point: What if a party won a majority and the ethnic parties don’t win? Elections will be dealt with after we have handled the issues of power sharing, resource sharing, and all of these things under the federal structure. It is clear. Democratic standards cannot be removed. Similarly, when you implement a federal system, we can’t say an election will be held in this state and not in that state. For example, let’s consider America, the model country for federalism. If we look at America, if the Democratic Party wins, the Democrats form the [federal administration] and take the presidency. So too, if the Republican Party wins, the Republicans form the administration and take the presidency. That’s how it is.