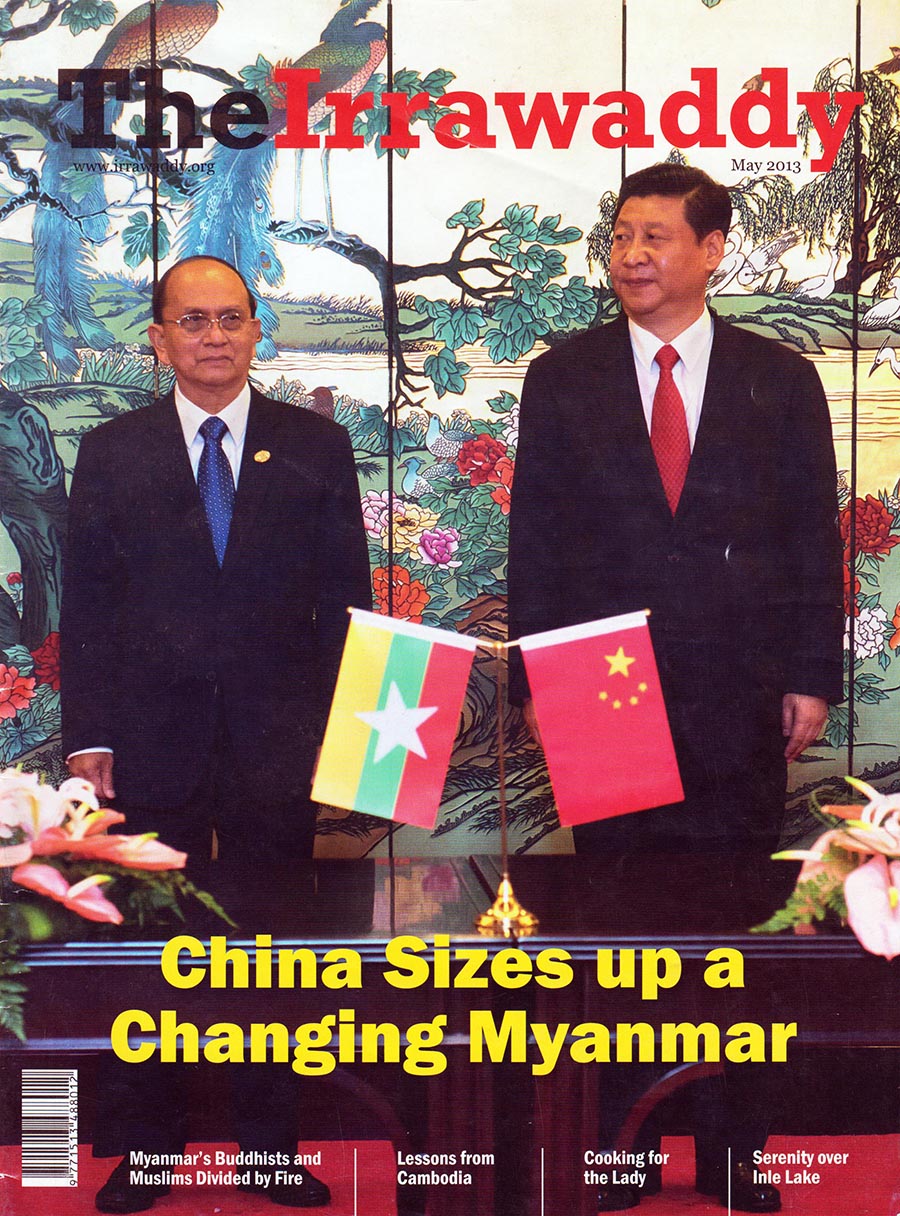

In this special report published in the May 2013 issue of The Irrawaddy magazine, Yun Sun wrote that China — at that time seemingly in danger of being frozen out of Myanmar’s economic opening — could take comfort in the knowledge that it can never be fully counted out of its neighbor’s affairs. In light of the fallout from the situation in Rakhine, the report seems especially prescient.

Burma’s democratic reform has produced both winners and losers. The country’s transition to democracy has revitalized the government, opposition groups and civil society, and it has brought the people unprecedented development opportunities. On the other hand, some former military leaders and cronies have lost their previous political status and economic privileges.

Externally, the West has applauded democracy’s victory in Burma and eagerly embraced the country’s rich business potential. However, one of Burma’s old patrons, China, has perhaps suffered most from the former pariah state’s unexpected waves of change.

Indeed, Burma’s reform has unveiled tremendous challenges and unpleasant uncertainties for China’s national interests. Suspension of the controversial Myitsone dam project in north Burma was seen as “a slap in the face” for China; the victory of “the will of the people” against the unpopular Chinese project encouraged broad scrutiny and criticism of other business ventures signed off by Beijing during the military government.

This anti-China criticism was particularly signified in the protests against China’s joint venture in the Letpadaung copper mine near Monywa in northwestern Burma. Other protests have raised concerns about the future of a strategic Chinese project to build oil and gas pipelines across Burma. Both countries seem to recognize that the pipelines, expected to be completed in May, are too important to jeopardize, but as Burma’s political, economic and social spheres continue evolving at dazzling speeds, uncertainty about the project has grown.

Politically, the preliminary success of Burma’s democratic transition has raised questions about China’s own political system and long-postponed reforms. Although official Chinese media have characterized Burma’s reforms as “too early to tell” and “untested by reality,” academics and media commentators cite similarities between the former military government and China’s authoritarian system, and they use Burma’s smooth democratic transition to argue for the necessity and feasibility of China’s own political reform. For the fifth generation of Chinese leaders stepping into their new positions, this is certainly not the most pleasant message.

In north Burma, the Kachin conflict has touched upon China’s sensitive nerves on border stability. There may not have been a causal relationship between Burma’s political reforms and the hostilities, which flared in June 2011, not long after President Thein Sein took office. However, there are rampant complaints from China about Thein Sein’s inability to control the military and stabilize the border.

This dissatisfaction directly resulted in China’s open intervention in peace talks between the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and the Burmese government in China’s Yunnan Province in February. In an unprecedented move, China assumed a mediation role in the internal conflict between the central government and a local rebel group in another sovereign nation. In this sense, China deviated from its traditional principle of non-intervention in other countries’ internal affairs, which has been the cornerstone of its foreign policy since the founding of the nation in 1949.

Yun Sun is a visiting fellow at the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution in Washington.Yun Sun is a visiting fellow at the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

The changing Burma has not been the best news for China’s strategic landscape on the global stage either. The dissolution of Burma’s international isolation and the country’s rapidly improving relations with the West have undermined Beijing’s original blueprint regarding the strategic utilities of Burma at regional forums to defend China’s unpopular positions and in the Indian Ocean to advance China’s strategic presence and national interests.

As Burma develops close ties with the West, China has seen rising competition with other powers inside the country for economic opportunities and strategic influence. This competition did not exist before the democratic reform. Among competing powers, the United States has been singled out as a main source of China’s mishaps in Burma.

Eyes on America

The US government has taken exhaustive efforts to reassure Beijing that US engagement in Burma is not targeted at China in any sense. Instead, US policy makers say engagement has been motivated by Burma’s democratic reform. According to an anonymous US diplomat, “To think that all we have done in Myanmar [Burma] is because of China is delusional and only reflects Beijing’s paranoia about the US.”

However, Beijing could not agree less. Chinese leaders firmly believe the US rebalancing to Asia is aimed at encircling China and curtailing China’s regional influence. In this vein, they reason that US President Barack Obama’s engagement with Burma, as a part of this rebalancing, must likewise be hostile to China. Leaked diplomatic cables about US government funding for anti-dam organizations before the suspension of Myitsone project have been cited as evidence of a US attempt to “sabotage” Chinese interests in Burma.

This antagonism has been reinforced by US actions that may remotely relate to China. American interest in the Kachin conflict and US Ambassador Derek Mitchell’s visit to Kachin State raised fears in China that the US would intervene and assert its presence right on the Chinese border. The United States has also invited Burma to observe the Cobra Gold joint military exercises in Thailand, leading to concern in Beijing that close US-Burma military ties might somehow threaten China’s national security either in the near term or the long run.

Even if Washington did not originally intend to contain China through its engagement with Burma, some analysts argue that Chinese interests have nonetheless been damaged as a result. For Washington to deny responsibility in China’s losses only reflects its lack of consideration and respect of China’s national interests.

Therefore, at a US-China-Burma trilateral dialogue in Beijing in December, when discussing how the United States and China could cooperate in Burma, Song Qingrun from the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, a government think tank, openly urged the United States “not to damage China’s interests inside the country and to take concrete measure to strengthen the Sino-US strategic mutual trust on Myanmar.”

Reacting to reform

In light of the perceived China-unfriendly changes in Burma, Beijing has not been slow to convey displeasure. Of the war in Kachin State, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs repeatedly issued harsh statements about the escalating conflict and expressed its concern over border security.

Economically, China also dramatically reduced foreign direct investment (FDI) to Burma last year. According to Chinese official media, FDI to Burma dropped from US $8.5 billion in 2011 to $1.02 billion in the first 11 months of 2012.

Given that China provided the majority of FDI to Burma in 2011, the reduction of investment inflow represents a major policy shift. The cutback might be justified in that the anti-China sentiment in Burma has created major problems for Chinese investments, but in the long run, its impact on Burma’s prospects for economic growth could be profound.

Official bilateral ties seem cordial to the public. Senior Burma leaders including Thein Sein and Shwe Mann, the speaker of Burma’s lower house of Parliament, have both visited Beijing since the nominally civilian government came to power in 2011.

However, during the peak of reforms between April 2011 and September 2012, none of China’s top leaders visited Burma. This constitutes a sharp comparison to three such visits before Burma’s democratization from March 2009 to June 2010.

Meanwhile, China is seeking to diversify its relationships with different political forces in Burma, including opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party. Beijing has also launched a major public relations campaign to improve its image and relations with local communities in the country.

Despite prior losses, China remains hopefully about the future of Sino-Burmese relations. This confidence stems from a belief that regardless of Burma’s political system or international status, China will always be its largest neighbor and China’s political, economic and social influence will always persist.

As Western companies hesitate on the best timing to invest in the country, China believes its abundant foreign investment could encourage closer Sino-Burmese cooperation once Naypyidaw realizes its ties with the West are not bringing the desired economic growth.

China recognizes this relationship may not be as good as during the junta years. However, as it observes and adjusts, the Asian superpower hopes for new opportunities.