Myanmar’s electoral authority, the Union Election Commission (UEC), has come under fire for its inclusion of ethnic areas considered relatively safe in a list of constituencies where the election cannot be held, depriving nearly 1.5 million of Myanmar’s 38 million eligible voters of their rights. Of them, more than 1.2 million reside in conflict-torn Rakhine State.

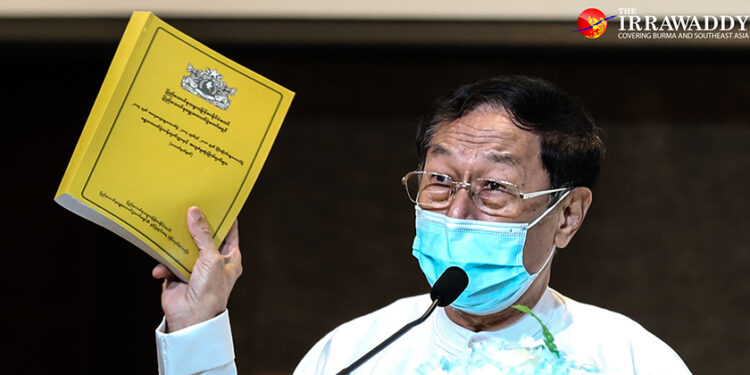

The UEC on Friday announced the cancellation of voting in all or parts of 56 townships nationwide, mostly in ethnic areas like Rakhine, Kachin, Mon, Shan and Karen States, saying merely that the areas are “unable to conduct free and fair elections.”

The list includes nine townships in northern Rakhine State—Pauktaw, Ponnagyun, Kyauktaw, Minbya, Mrauk-U, Myebon, Rathaedaung, Buthidaung and Maungdaw. In most of these, the military and the Arakan Army have clashed frequently since late 2018.

While the appearance of many of Rakhine State’s conflict-ridden townships on the list is understandable, the motive behind the UEC’s inclusion of other areas in parts of Shan, Kachin, Karen and Mon States and Bago Region that can be considered relatively stable is questionable.

Of the six townships in Shan State where no voting will be held, four—Pang Hseng, Nahphang, Mongma and Pangwai—are under the control of the United Wa State Army, and Mong La is under the control of the Mong La armed group.

Furthermore, the list doesn’t include Paletwa in Chin State, a flashpoint of fighting between the two armies, prompting questions about the criteria used by the UEC.

In its announcement, the UEC said only that the constituencies on the list are those experiencing a “situation where free and fair elections could not be held,” without offering details for each case. A UEC spokesman could not be reached for comment at the time of publication.

The UEC must explain its criteria and the reasons for its decisions, said Dr. Min Zaw Oo, the director of the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security.

“Paletwa had more clashes than any other townships that we documented. It is the only township which needed security support to transport food to the locals. If it can hold elections, why not the other constituencies?” he asked.

If the election goes ahead under these circumstances, he said, the result would be questionable, and this would affect the peace and national reconciliation process with the ethnic armed groups.

Rakhine has 1,649,753 eligible voters for the 2020 election, but now only 448,855 will be able to cast ballots, according to the Rakhine State electoral sub-commission. Over 9,000 early ballots cast at embassies and consulates around the world this month by people from the affected areas have gone to waste, said U Thu Rein Htut, the secretary of the Rakhine State electoral sub-commission.

Rakhine politicians questioned the UEC’s motive, as some of the townships in northern Rakhine where voting has been canceled are currently free—entirely or partially—of fighting.

If the UEC made the decision based on security reasons, then the inclusion of Pauktaw, where there is no fighting, is questionable, said U Aung Kyaw Htwee, a current state lawmaker from the Arakan National Party (ANP) representing Pauktaw Constituency No. 2.

He said he was surprised by the UEC’s decision, as “there was neither fighting nor the sound of gunfire in Pauktaw. If security is the reason, why would Chin State’s Paletwa be able to hold an election, where fighting has been rampant?” he asked.

The lawmakers said these constituencies are also strongholds of Rakhine political parties such as the Arakan National Party (ANP) and Arakan Front Party (AFP), adding they feel sorry for voters who have lost their rights.

In 2015, the ANP won 33 out of 36 seats from these nine townships, where the NLD lost in all seats.

U Kyaw Lwin, a current state lawmaker representing Kyauk Phyu constituency and the co-founder of the AFP, said, “The political arena is shrinking,” as residents in fewer townships can exercise their right to choose.

As Kyauk Phyu is not in the fighting zone, and police are present to uphold the rule of law, he said, security shouldn’t be the reason.

“It badly affected the Arakan Front Party too,” said U Kyaw Lwin, because the party had mobilized its supporters in most of these townships. He is a candidate for Rakhine State’s Upper House Constituency 1, in which Kyauk Phyu and Manaung townships are included. He added if there are fewer members of Parliament to represent the local people, the armed forces’ power will keep getting stronger in the state, pointing out that those areas where voting is canceled in Rakhine State are now regarded as AA-controlled areas.

In southern Shan State’s Mong Kung Township, the election will not be held in 2020, so over 56,000 eligible voters have lost their rights.

“Mong Kung is peaceful at the moment. We did not know in advance about the UEC decision and we were not asked about the township’s situation, including security,” said Nan Hla Htay, the chairperson of the Mong Kung township electoral sub-commission.

However, in Mong Kung, the Ta’ang National Party (TNP) earlier this month made electoral complaints to the UEC, as the TNP candidates halted campaigning in Mong Kung where ethnic Shan and Ta’ang (Palaung) are residing, alleging troops of an ethnic Shan armed group, the Restoration Council of Shan State, were making threats against them. The TNP said it could not canvass in some areas because of the RCSS troops.

Sai Nyunt Lwin, the vice chairman of the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, a popular party among ethnic Shan, asked why the UEC made such a decision not to hold the election in Pauktaw and Mong Kung, where there are no security concerns or health-care emergencies like in Yangon, the country’s COVID-19 hotspot.

Over the weekend, observers and Facebook users who are politically active residents of Kachin, Karen, Shan and Rakhine states decried the UEC’s decision.

Many said that there were many villages among the 141 wards/village tracts in 17 townships across Shan State and 192 village tracts in Kachin State’s 11 townships that should be able to hold the election.

Similar questions were raised about why the UEC banned the election in one village in Mon State’s Bilin township; 42 village tracts in Bago Region’s Kyauk Gyi and Shwe Kyin townships; and 53 village tracts in six Karen State townships. Critics said these are under partial control of ethnic armed groups the Karen National Union.

You may also like these stories:

Myanmar Military Calls in Jets to Attack Arakan Army in Rakhine State Mountains

Myanmar’s Military Transfers Officers to Police on Bangladesh Border

Ta’ang Rebels Shell Myanmar’s Troops in Northern Shan State