There is something about Myanmar that induces the internal fruit-loop of so many Westerners to burst forth. Or, at the least, enables that pulsating loon a delusional playground to thrash around in. If there is a defining characteristic of the Western branch of the democracy and human rights movement since 1988, it would be a spectrum ranging from the serious scholar, committed activist, aid worker and health specialist all the way through to the harmless nut-bag and the hard-right of the deranged, destructive fantasist.

This has produced a minor canon of self-promotional reportage that has had some hand in shaping international perspectives on Myanmar. Often the completely wrong ones.

Joining this odious oeuvre are the laughingly self-important memoirs of Amaryllis Fox, who got her start as a death-defying Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) super spook amidst the intrigue of the Myanmar exile activist movement along the refugee camps of the Thailand/Myanmar border. Or so she says. Fox’s Life Undercover-Coming of Age in the CIA (Alfred A. Knopf, 2019, 230 pages), according to a gushingly uncritical review in the New York Times, reads as if “a John le Carre character landed in Eat Pray Love.” Yes, it’s that bad.

Fox is an unabashed narcissist rich-kid, who traveled to the Orient looking for internal meaning, inspired by a high school assignment profiling Daw Aung San Suu Kyi: “I stick a picture of her on my wall and stare at it. There’s steel in her eyes, but she wears a flower in her hair. This feminine warrior for peace. I’ve never seen anything like her before…one single conscience that’s brought an entire army to its knees.”

So cashing in the money for her prom dress, Fox buys an air ticket to Thailand to become a volunteer teacher in refugee camps on the border (that would have been a pricey dress). She becomes enthralled with a small group of mysterious Myanmar student activists based in a secretive “treehouse” (it’s a hut on stilts) and enters the underground life. The activists convince her to travel into Myanmar to film potential protests ahead of the symbolic date of 9/9/1999. She doesn’t have a camera, but knows an older investment banker called Daryl who does.

Her mission identifies Fox as a “pigeon”; one of numerous Westerners who obtained visas to Myanmar to transport supplies, funds or produce multimedia to support the political opposition and get news out during the dark years of military rule when entry requirements were eased.

Fox and Daryl adopt a “legend” as honeymooners and enter the terror-dome of Yangon, or so she paints the experience of the city, which doesn’t exactly jive with other experiences at the time when Immigration officials weren’t soldiers, and tour guides were not mandatory, and not every foreigner was tailed. She ventures to a dead-letter drop at the ABC Cafe, where her activist contact in Thailand has left a cryptic note in the water tank of the toilet: “Order the French fries”, an experience Fox equates to “teleportation.” She ordered the French fries.

The planned demonstrations on Sept. 9 fail to eventuate, possibly because there was a significant student protest movement in late 1996 in Yangon which was violently crushed, and the 10th anniversary of the 8.8.88 Uprising passed with little more than a tepidly orchestrated flash protest by 18 foreign activists who handed out protest cards to people on the streets, fled to the airport and were arrested and detained for a week and then deported.

So the newlyweds are tasked to interview Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, as Fox claims, at the headquarters of the National League for Democracy (NLD) near Shwegondaing. Every cliché, trope and canard about Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is included in Fox’s recounting: “I’m mesmerized, listening to this tiny woman tell me the ways nonviolence in the streets and the courts can deliver a ruthless military to its demise.”

After the interview, as Fox endeavors to secrete the film in a Bic pen, “Suu Kyi puts her hand on mine. ‘Those are fine for the decoy film’, she says. ‘The scraps you want them to find so they think they’ve gotten it all.’ Then gently, like a patient godmother, she adds, ‘For the real footage, the film you actually want to get out, nature has given you a better hiding place.’ She rolls the film of our interview into a cylinder smaller than a tampon and seals it in plastic wrap. She hands it to me and says, ‘The bathroom is down the hall on the left.’”

I find this account of events implausible for two reasons. The first is that I cannot imagine Daw Aung San Suu Kyi being, in a manner of speaking, so hands on, over the logistics of smuggling contraband. Secondly, the secreting of videotape through anatomical exigencies Fox outlines seems improbable to the point of impossibility. It invites an alternative rendering of the term ‘diplomatic pouch.’ People I know who actually did film in Yangon at this time and smuggled it out scoffed at this account.

Fox and her “husband” are immediately arrested by officers of the Myanmar army, or Tatmadaw, outside the NLD office and taken by jeep—“I listen for the sounds of Shwedagon Pagoda and Inle Lake, which we’ll pass on the way to the airport” (pagodas don’t make sounds, people do, and she must have Bionic Woman hearing to discern a lake hundreds of kilometers away in Shan State)—to an alleged black site near Mingaladon airport. The honeymooners are guarded by prepubescent, drugged out soldiers and hear people being tortured in a room next door: “Car battery”, one of the lads tells her. But Fox and Daryl are let go to fly back to Thailand: “I can feel Suu Kyi’s words tucked inside me, and I know that today the soldiers have failed.” Fox writes like Dora the Explorer on cheap hallucinogens.

Next she goes to study at Oxford, “to follow in the footsteps of Suu Kyi…and one day do my part to challenge tyranny on behalf of the powerless.” And then eventually joins the CIA. That’s an odd platform to challenge tyranny, given the track record of the Agency in propping up dictatorships, engaging in torture, rendition, assassination and a number of coup d’états.

The remainder of this “coming of age” tale is as improbable as the opening scenes at the border or in Yangon, with Fox then studying at Georgetown University where she claims to develop an algorithm that predicts terrorist recruitment patterns, leading to her approach from the Agency. While this may indeed be correct, it’s hard to believe a pugnacious college student could conceive something that the combined American intelligence budget of US$80 billion or the mega-economy technocracy of Silicon Valley hadn’t thought of.

After her stellar training at “The Farm”, the CIA’s secret training facility, so clandestine it’s an established storyline in Hollywood films, Fox goes “deep undercover”, posing as an art dealer posing as an arms dealer. She gets married (the relationship doesn’t work out), has a child and then ends up convincing a jihadi terrorist not to detonate a dirty bomb because she appealed to him as a caring parent. If only the “War on Terror” followed lifestyle advice from Goop. She eventually leaves the Agency, gets a book deal, and her incredible final lines are quoting the motto of the CIA: “And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.”

Having been a peripheral player in some of the pigeon activism over the years, there is no doubt that a considerable amount of invention went into the infiltration and exfiltration of clandestine goods. But Fox’s account sounds not just hysterically dramatic, but large parts totally invented or traumatically misremembered. If you can bring yourself to read this book, you’ll quite likely land on the “mostly invented” interpretation. It’s like Fox went on a bender and binge-watched seasons of the American TV spy drama Homeland, waking from a stoned stupor convinced she had lived a similar life.

Fox’s book is merely the latest in a nearly a three-decades-long competition for producing the most narcissistic account of Western misadventures in Myanmar’s civil strife. Mae Sot up until a few years ago was a teeming border town of migrant workers, refugees, rebels, health workers, and exiled intrigue, and swirling on the margins was a small foreigner contingent that mostly did quiet and important work, in spite of the circus sideshow freaks of mercenaries, swindlers, lunatics, and predators. No one captured this milieu better than Phil Thornton in his classic Restless Souls, based on extensive time on the border and piecing together a tragic mosaic of lives indelibly impacted by war and repression.

But several people really stood out for their uniquely bonkers behavior. James Mawdsley, a British-Australian teacher makes the top of the list. His memoir, The Heart Must Break, details Mawdsley’s time as a teacher at an All Burma Students’ Democratic Front camp on the border, who decided on a more direct action approach which entailed flying into Yangon and handing out pro-democracy leaflets, allegedly by chaining himself to a school gate. Another time, after trekking through the jungle from the border to Mawlamyine in Mon State, his shtick was less effective as it was a holiday and school was out. The third attempt was just across the Thai border into Tachileik, and this time the authorities took harsher measures, throwing him into Kyaintong Prison after a trial handed down a 17-year sentence for sedition, serving several months. His father, interviewed in The Guardian, praised his son’s actions in curious terms, “a large part of me wants him to stay [in jail]…I know that the moment he’s back here [in Britain], that will be the end of the public interest in the situation in [Myanmar].” Mawdsley, and his atrocious book, sank into history. His father failed to comprehend that it was James and his crank antics that was of no public interest.

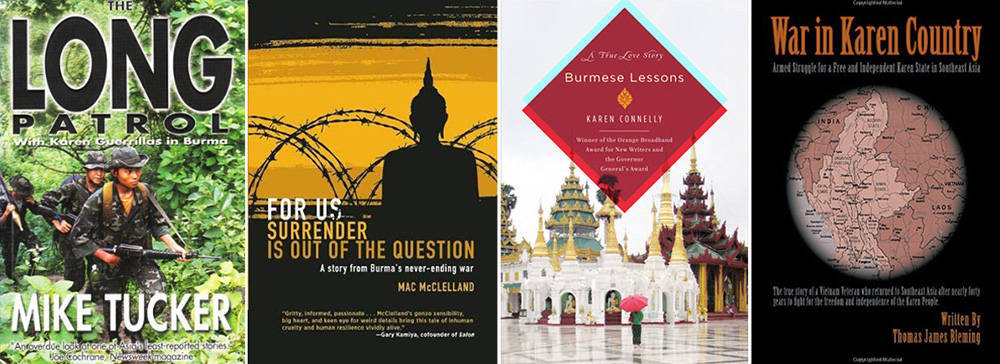

The slew of terrible books by faux adventurers started to pile up, many of them fetishizing the long-standing Karen rebellion, their authors becoming groupies of the Karen National Union (KNU)/Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA). A real standout is Mike Tucker’s hilariously macho and dishonest The Long Patrol (it only lasted a few days), Thomas Bleming’s nonsensical War in Karen Country (the author claims to be the KNU’s representative in Lusk, Wyoming), and Nelson Rand’s dishonest reporting from the “frontlines” in Conflict.

One exception is the endearingly larrikin-esque Shadow Warrior, by David Everett, a former Australian Special Air Service (SAS) trooper who came to the border as an advisor to the KNLA, and then went on to be an armed robber and Australia’s most wanted criminal. Everett’s mis-adventures may have landed him in prison, but his honestly drawn account of his commitment to the Karen cause deserves respect, and it is, employing that old trope of book reviewers, a “rattling good yarn”.

There were the early genocide claimers, in particular the Christian activist Ben Rogers and his first book A Land Without Evil (Rogers books on Myanmar never improved from this flaccid beginning, his biography of Than Shwe is a shallow watermark of Western understanding of the country), Daniel Pedersen’s incomprehensible Secret Genocide, and Guy Horten’s Dying Alive report, which was more a cut-and-paste human rights compilation with a specious legal analysis overlaid. Horton put his own myth-making ahead of the serious claims of systematic human rights abuses in a slew of disturbing media interviews, in which he claimed he hid from marauding Tatmadaw soldiers fixing bayonets outside a hut he sheltered in, being evacuated towards the borderline atop a septuagenarian elephant who knew how to avoid landmines, and running afoul of the goon squad in Mandalay for mentioning Daw Aung San Suu Kyi at a teashop: “Two ferocious undercover policemen immediately came up to me, both over six foot and disguised as monks, and started pushing me around.” Horten, like Fox, was a one-shot poseur, and drifted into obscurity soon after.

And let’s not forget the unfortunate escapades of the American John Yettaw, the delusional “swimmer” who made unwelcome visits to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s compound in 2009, leading to his arrest and the extension of her house arrest order after a farcical trial. Yettaw’s plan involved donning burqas for him and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to escape through the compound’s main entrance past the guards. We’re mercifully spared a book from those delusional swims, which would have included his forays to Mae Sot for guidance from the exiled community, who gently advised him to go home.

Karen Connelly’s Burmese Lessons contains some rip-snorting self-promotion and possibly the most excruciating sex-scene in the history of Western engagement with Myanmar. You’ll never look at the Moei River the same way again. Like Fox, Connelly has the ubiquitous encounter with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the authentic leitmotif of Western adventurism during the dark days of military rule. Mac McClelland’s obnoxiously distorted account of a few months on the border, For Us Surrender Is Out of the Question, is, like Fox again, a lesson in why short-term and uninformed American volunteers to the world’s humanitarian emergencies should be barred from writing books.

Within this milieu of book-deal chancers were a whole ecosystem of well-meaning Western do-gooders. Mae Sot attracted a never-ending stream of almost interchangeable VERY SERIOUS MEN: white foreigners who pursued self-advancement by working with local human rights groups and exiled media, adopting knucklehead pseudonyms and reveling in a constant state of nervous intrigue. After 2011, many of these VERY SERIOUS MEN moved to Yangon to work in the bloated INGO field, again becoming indistinguishable because of their VERY SERIOUS MANNER and because they all look the same: several days’ facial growth, button shirt, skinny jeans and Myanmar slippers, the “tropical hipster” look. In Mae Sot, Western women activists were all in “ethnic chic”: htamein-wearing, Karen shoulder bag-toting, patchouli oil-drenched earnestness for freedom and rights, and a slew of dreamy long-haired Myanmar student revolutionary soldiers to ogle. It was like an academy for temporal outrage at injustice, but most of them wisely eschewed a book-equals-fame-and-advancement route for deeply committed hard work.

Many of these volunteers, supposedly like Fox, were recruited as “pigeons” over the years to dart into Yangon and drop off supplies and funding with their amateur tradecraft. These were separate cells of couriers, from human rights solidarity groups, the student underground, and labor activists, including the American trade union group the AFL-CIO; you can imagine the sly wit many Myanmar exiles exercised mispronouncing the last letter of that acronym.

Risible memoirs such as Life Undercover unfortunately provide added ammunition for the sneering dismissal of refugee and exiled efforts to advance a just society in their own country by post-“transition” diplomats and peace-industrial complex scoundrels who cling to the dismissive objectification of “the border” over their own technocratic, a-historical superiority. It’s remarkably easy to ridicule Fox’s book, and stupefying how many Westerners have used and abused the long, grueling struggle of people from Myanmar for their own advancement.

Rejecting Fox’s idiotic account and its dramatically dishonest author is necessary, for no other reasons than remembering the many individuals from various communities who helped in small but impactful ways on health, education, political socialization, human rights, and media development, in Mae Sot, refugee camps and in the conflict zones along the jagged edge of the border.

David Scott Mathieson is an independent analyst working on conflict, peace and human rights issues.

You may also like these stories:

Confessions of Two Military Men Illustrate the Myth of ‘One Voice’

Reading Myanmar—‘Miss Burma’ and the Liberal Conscience

‘Have Fun in Burma’: A Fictional Exploration of Intercultural Misunderstanding