In this special edition, The Irrawaddy looks at the individuals who most influenced the news headlines both locally and internationally throughout the year — from the Rakhine conflict to the murder of prominent Muslim lawyer U Ko Ni to the journalists who were arrested just for doing their jobs to the significant first papal visit. Some of these people ended the year with their good names enhanced, others with their reputations tarnished.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi: Leader Under Siege

2017 was a rocky year for State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Peace with the major ethnic armed groups in the country remains elusive despite her commitment to ending the world’s longest-running civil war. Her hopes of national reconciliation with the country’s powerful military are far from being realized. Western countries that once hailed her as a “saint” are now criticizing her after more than 650,000 Rohingya fled the country due to a military crackdown the UN labeled ethnic cleansing.

In Myanmar’s capital, Naypyitaw, she has effectively taken charge of all 24 ministries because “some ministers don’t dare to make decisions by themselves,” as her aide U Win Htein put it. Despite accusations of incompetence against some cabinet members, the de facto leader has yet to replace any of them. Instead, she has hailed her cabinet as corruption free. It would be more helpful for the 72-year-old if her ministers had a clear and precise vision of what they were doing apart from not being corrupt.

Though her popular support in the country remains unshakable, people are starting to feel uneasy about the slow pace of change. The business community is wondering why she has neglected much-needed economic reforms. A recent survey found that business confidence among entrepreneurs had dropped from 73 percent to 49 percent over the past year due to a lack of clear economic policies. In the markets, housewives are complaining about rising commodity prices. Rule of law in the country is still uncertain. In a speech in March marking her NLD party’s first year in power, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said her government wanted to make changes together with the people. But the changes her people are now experiencing are not exactly the ones they want. On the other hand, there is no one else who has earned the public trust to lead the country as of yet.

____________________________

U Ko Ni’s Murder: A Signal from Hardliners

Myanmar’s community of pre-democracy activists was rocked in 2017 by the violent death of prominent Muslim lawyer U Ko Ni. He was gunned down at close range in broad daylight outside of Yangon International Airport on Jan. 29. The gunman, Kyi Lin, also fatally shot an airport taxi driver, U Nay Win, while attempting to flee. Kyi Lin was apprehended at the crime scene.

U Ko Ni was a human rights lawyer and constitutional expert who had long lobbied for the drafting of a new national constitution in accordance with democratic norms. Many speculated that his agitation for constitutional change was the reason he was killed. The 65-year-old lawyer was also a legal adviser to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party.

A trial has been going on for nine months for Kyi Lin and three other suspects accused of involvement in the assassination. However, former lieutenant colonel Aung Win Khaing, who is also on the police’s wanted list as a main conspirator behind the assassination, is still at large nearly one year after the murder. Police told a Yangon court in June that they had made no progress in their effort to arrest him.

The motive for the murder, according to the minister for home affairs, was a “personal grudge” on the part of the arrested suspects, who he said were “resentful” of U Ko Ni’s political activities. However, many suspect the involvement of more powerful people eager to put an end to the reform efforts of the prominent NLD lawyer.

____________________________

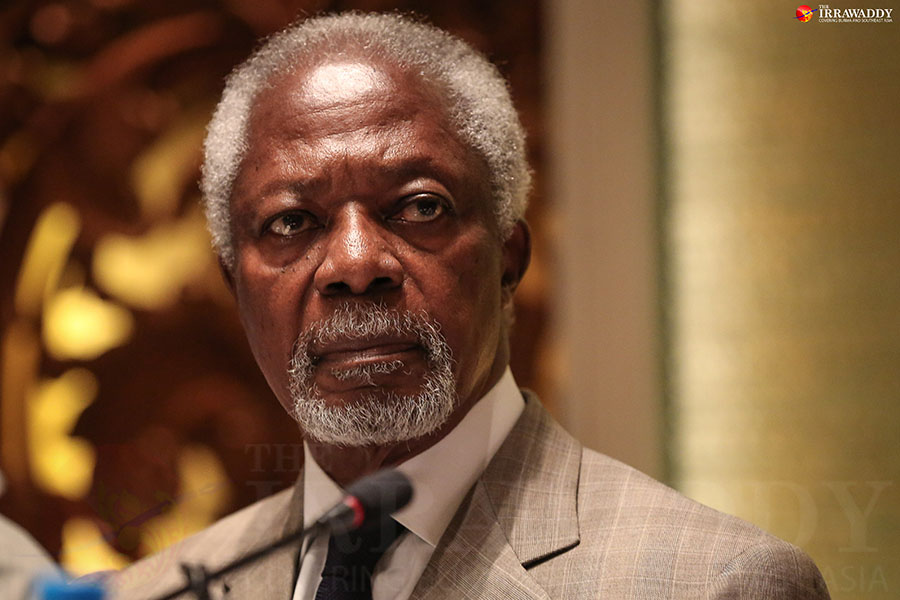

Kofi Annan: Adviser on Harmony

In late August 2016, State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi appointed former United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan to chair a nine-member Advisory Commission on Rakhine State. The commission was tasked with finding lasting solutions to the deep-seated problems between the Rohingya and Arakanese communities. Annan made an official visit to Myanmar in September of that year. The following month, a group of Muslim militants attacked several Maungdaw border outposts, killing nine policemen and stealing firearms on Oct. 9.

During his visit, Annan conducted meetings with members of the Rakhine and Muslim communities, Muslim religious leaders and Buddhist monks across the state. These meetings formed the basis of the recommendations in the commission’s final report for Myanmar’s NLD-led government. However, Annan acknowledged that the attacks in October had caused trust between the Muslim and Arakanese communities to break down again.

While the international community accused government security forces of committing rights violations in Maungdaw, Annan confined himself to trying to achieve the commission’s main objectives — conflict resolution, humanitarian assistance, reconciliation and development — rather than compiling human rights reports. Moreover, he warned the press not to use the word “genocide” loosely. Myanmar President’s Office spokesman Zaw Htay described the peace envoy as serving as a “shield” for the government in the international arena.

On Aug. 24 of this year, the Annan commission issued its final report and recommended the government amend the outdated 1982 citizenship law to bring it in line with international standards, and grant birth certificates to newborn Rohingya children. The report also contained recommendations on humanitarian assistance, infrastructure development and border security issues, and called for the acceleration of the national verification process and an end to segregation between the two communities. He publicly denounced the coordinated attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army that occurred the following day.

____________________________

Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing: Guardian of the Constitution

Myanmar Army chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing has received sharply split reviews for his response to the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army’s attacks on government security outposts in northern Rakhine State in August. He took the attacks as a threat to national sovereignty and security and with the government’s approval ordered clearance operations against the Muslim militant group. For the first time in decades many Myanmar people united behind the military, sharing the commander-in-chief’s views on the situation.

But with a rising number of Rohingya refugees fleeing to Bangladesh with horrific accounts of mistreatment at the army’s hands, much of the rest of the world is of a different mind. The army chief’s repeated denials that his soldiers committed atrocities against Rohingya have made no difference. Sanctions on military leaders by the European Union and the United States followed. Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing’s dream of creating a modern military has been shattered.

The military’s ostracism by the West has pushed it closer to Myanmar’s neighbors, especially China, which has vast business interests in the country. On a visit to Beijing, Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing was welcomed by Chinese President Xi Jinping with firm support for military-to-military engagement and for the army’s actions in Rakhine State. The recognition buttressed Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing’s position and the military’s role in Myanmar politics.

At home, when it comes to local politics, the military chief frequently cites controversial provisions in the country’s Constitution guaranteeing the military’s political role and enshrining it as the sole guardian of the charter. His relationship with State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who wants to amend the constitution to make it more democratic, is at a low point, according to some insiders. The general’s call for all ethnic armies to join the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement is unlikely to gain much traction while his troops in northern Myanmar are shelling rebel camps. For ethnic people who fled their homes in the face of army offensives, it means they will have to spend some more time in the squalid IDP camps they have called home for years.

____________________________

Ethnic Armed Groups: Fighting for Rights and Peace

State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi spoke a lot about peace in 2017, but the peace process has lost momentum since her government took over from the U Thein Sein administration two years ago. She herself has expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of progress; since her National League for Democracy was elected, none of the ethnic armed organizations from the UNFC or the Northern Alliance has agreed to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). The UNFC has long said it would sign the pact if the government agreed to address its eight points, but the Tatmadaw — Myanmar’s military — has balked. At the last round of meetings on peace talks in October, progress was held up by differences over a single phrase in the agreement. The UNFC wants the country to be officially described as a “Federal Democratic Union,” whereas the Army and government favor “Democracy and Federal Union.” The UNFC believes that once all ethnic groups have equal rights under a federal system, democracy will follow, but the Army has a different view.

Some UNFC leaders believe the Army is trying to deny the NLD-led government credit for achieving peace by making it impossible for the UNFC to sign the NCA.

Myanmar has been through multiple peace processes and political dialogues, but they have never been entirely inclusive. According to U Khun Okkar from the Pa-O People’s Liberation Organization, the Tatmadaw has conducted the process in the wrong order, writing the Constitution first, before seeking political dialogue. He said that if everybody can be brought into the talks, and a common agreement found, the country will have lasting peace and a stable constitution. In the case of the Northern Alliance, the Army wants participation in the peace process limited to the UWSA, NDAA, KIA, and SSPP, with the MNDAA, AA, and TNLA excluded.

Despite the talk of peace in 2017, we will not see actual peace until the Tatmadaw gives the green light to all armed groups to participate in the peace process.

____________________________

Dr. Win Myat Aye: Minister of Goodwill

Widely recognized as a reformer, Minister of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement (MSWRR) Dr. Win Myat Aye has improved the image of his ministry, which was long seen as one of the least active in the government.

He has developed a reputation for responding quickly to problems and engaging with civil society in order to address the issues facing his ministry—from caring for young children and senior citizens to protecting women’s rights and the rights of people with disabilities, as well as disaster response.

Unlike other ministers, he is always responsive to media, even amid a tight schedule.

Trained as a pediatrician, he once served as rector of Magwe University of Medicine. He won an Upper House seat in Bago Division representing the NLD in the historic 2015 general election.

The minister said he was told by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi before he took office that the image of the new government would depend greatly on the performance of his ministry.

“We’ve adopted a policy that our ministry should be close to the people. We know that we have to reach out to the people. This policy is about responsiveness to public issues,” he said.

As the most highly regarded NLD cabinet member over the past two years, Dr. Win Myat Aye was given two important posts: chairman of the Implementation Committee for Recommendations on Rakhine State (in September) and vice chairman of the Union Enterprise for Humanitarian Assistance, Resettlement and Development in Rakhine (in October).

These positions make the minister a key figure in the implementation of both short- and long-term solutions for ethnically and religiously divided Rakhine State, including the voluntary return of refugees, restoring stability, preventing human rights violations, fighting terrorism, working to achieve harmony between the different communities, and implementing economic and social reform.

____________________________

Tycoons: Offering a Financial Lifeline

The saying “a friend in need is a friend indeed” couldn’t be more apt in the case of Myanmar’s embattled de facto leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. When the country needed money in the wake of the Rakhine conflict for large-scale rehabilitation programs, she seemed to have no one except rich businesspeople to turn to, declaring that “Big businesspeople are the strength of the country.”

The state counselor had called on her fellow citizens to help in Rakhine at a time when the country faces potential funding delays and cuts from international organizations due to the crisis. In response, she was showered with K17.7 billion (about USD13 million) in cash donations from the country’s leading 25 business tycoons, including U Aung Ko Win of KBZ Company, U Zaw Zaw of the Max Group, and U Khin Shwe of the Zaykabar Group.

Apart from money, she asked for suggestions and collaboration from the business community to solve the problems in Rakhine in the form of job-creating opportunities, infrastructure building and programs to improve transportation and agriculture. The country’s leading business body, the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI), organized taskforces to implement the plans.

Of the country’s leading business executives, Nang Lang Kham of KBZ group and U Zaw Zaw of Max Group of Companies appear to be the state counselor’s favorites. During her recent trip to Rakhine State, they were right beside her.

Nang Lang Kham, executive director of the KBZ Group, is renowned for her activism for women’s empowerment and the work she does through the Brighter Future Myanmar (BFM) Foundation—the philanthropic branch of KBZ, which she co-founded and chairs. In the government’s Rakhine State rehabilitation projects, BFM was ranked as the top donor thanks to a K6.5 billion ($4.7 million) contribution. Through the foundation, Nang Lang Kham has been actively engaged in disaster relief and supporting health, sport, peace and education programs since 2007, as well as in promoting inclusivity and gender equality.

U Zaw Zaw, once known for his close ties with the military regime, these days is mostly recognized for his backing of Myanmar soccer, a popular sport in the country.

The former blacklisted tycoon once said he at least wants to try to be “a good crony”. To make it happen, he began cultivating a relationship with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi shortly after her release from house arrest in November 2010.

He has been doing philanthropic projects in healthcare, education and youth development through his Ayeyarwady Foundation. In Rakhine, the foundation has donated K2.33 billion ($1.7 million).

Furthermore, he has opened football academies in Yangon and Mandalay to train promising young players. When he met FIFA president Gianni Infantino in London in October this year, U Zaw Zaw discussed Myanmar’s football development, even expressing his wish to one day see Myanmar host the World Cup.

____________________________

Half the Sky: Groundbreaking Women

In 2017 women featured in the news more than in years past. They now account for 13 percent of the country’s 1,151 elected lawmakers. Though far outnumbered by men, female parliamentarians were more outspoken than their male counterparts.

Rights advocates turned lawmakers like Daw Thandar, Naw Susana Hla Hla Soe and Daw Zin Mar Aung, and businesswomen like Daw Thet Thet Khine are among them, playing key roles in Parliament. Legislation on the prevention of violence against women and children, drafted four years ago, was at last finalized and readied for submission.

Daw Thet Thet Khine questioned the transparency of revenues from the country’s extractive industries in November. She pointed out that only half of more than 10 trillion kyats ($7.3 billion) in revenue went into the Union budget, the rest kept by state enterprises controlled by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

With two NLD women as chief ministers, in Karen State and Tannitharyi Region, under the country’s de facto leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, female leadership became more visible than ever before. Karen State Chief Minister Daw Nang Khin Htwe Myint is a veteran politician who has devoted her life to equality and federal union. She came under harsh criticism for moving forward with a coal-fired power plant project in Pa-an, the state capital. “If coal is useful for our state, I want to start using it,” she said. “We won’t, however, accept any development that damages the health of people and the environment.”

But women were most active in civil society. Tireless educators like Daw Khin Ma Ma Myo inspires other women to take part and contribute their knowledge about gender equality, peace and security. The security expert cofounded the Myanmar Institute of Peace and Security Studies. Female activists like Nang Phyu Phyu Lin and her colleagues, meanwhile, pushed for a 30 percent quota for women in the peace process.

Women are traditionally known for providing social support and care for vulnerable people. Renowned physicians like Dr. Cynthia Maung, who works along the Thai-Myanmar border, have been setting an example for others.

This year, Dr. Myat Sandar Thant launched the Single Mother Foundation to help pregnant young women abandoned by their partners give birth. Within six months of opening her shelter, she helped deliver 57 babies. The stories of the women who passed through her shelter drew public attention to the problem of sexual abuse against women and the lack of knowledge about reproductive health.

____________________________

Journalists: A Job that Requires Courage

It has been a tough year for journalists in Myanmar. Recent arrests have shed light on the vulnerability of journalists working in a country where authorities or individuals can target them at any time.

Ko Swe Win, the editor-in-chief of Myanmar Now, is still facing trial after being hit with a lawsuit in March under Article 66 (d) of the Telecommunications Law by a Mandalay nationalist who accused him of insulting ultranationalist monk U Wirathu on social media.

In June, the chief editor of The Voice Daily newspaper, U Kyaw Min Swe, and a columnist for the paper, Ko Kyaw Zwa Naing, were arrested after the military filed a lawsuit under the same telecommunications law and Article 25 (b) of the Media Law for allegedly defaming the Myanmar Army in a satirical article.

The Irrawaddy’s senior reporter Lawi Weng, and Democratic Voice of Burma reporters U Aye Nai and Ko Pyae Phone Aung were arrested by the Myanmar Army as they returned from an area controlled by the Ta’ang National Liberation Army in northern Shan State. The journalists were charged under the colonial-era Article 17 (1) of the Unlawful Associations Act and were kept behind bars for 67 days in Hsipaw Prison until the military dropped the charges.

Turkish TRT World’s Malaysian producer Mok Choy Lin, Singaporean cameraman Lau Hon Meng, and two Myanmar employees—interpreter Ko Aung Naing Soe and driver U Hla Tin—were sentenced to two months in jail under the 1934 colonial-era Myanmar Aircraft Act for flying a drone near Parliament in Naypyitaw.

On Dec. 12, two Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, were arrested on the outskirts of Yangon and accused of violating the Official Secrets Act for processing confidential police reports containing detailed information about the fighting between government forces and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army in late August 2017. They are facing a maximum sentence of 14 years.

All of the arrests are undoubtedly linked to the work of the journalists, heightening fears of a clampdown on the country’s independent media.

Editor’s Note: TRT Journalists and their two local staff were released on Dec 29.

____________________________

Pope Francis: Mediating Voice of Moral Authority

Pope Francis made the first papal visit to majority-Buddhist Myanmar at the end of November, amid unrest and a humanitarian crisis in Rakhine State.

The visit was a blessing for Catholics in Myanmar, who make up some 1 percent of the more than 50 million population. However, it garnered criticism from the international community.

Pope Francis first met with Army Commander-in-Chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing — ahead of President U Htin Kyaw and State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Critics noted the deviation from protocol.

The Vatican acknowledged this, but the pope reported that his meeting with the senior-general — whose army has been accused of widespread human rights abuses against the Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State — was productive in that he was able to make his message known.

Pope Francis called for peace and reconciliation and urged people to use their differences to forge unity, forgiveness, tolerance and nation-building.

The international community was disappointed that Pope Francis avoided using the term ‘Rohingya’ while in the country. He was reportedly urged by Myanmar’s Cardinal Charles Bo and others to avoid mentioning the term so as not to upset the host country or trigger a backlash. According to Reuters, the Vatican defended the decision and added that the pope’s moral authority was unblemished and that his presence alone drew attention to the refugee crisis.

Religious leaders from Myanmar described the visit as a success, sending a message of love, peace, justice and religious harmony.

____________________________

International Community: Friends or Foes?

Muslim militants attacked several border outposts in Maungdaw in October 2016. The Myanmar Army hunted for the perpetrators, but the operations resulted in thousands of Rohingya refugees fleeing and saw dozens of Rohingya villages reduced to ash. International human rights organizations accused the government security forces of arson, extra-judicial killings and rape.

In 2017, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army again staged attacks on border posts in three townships in northern Rakhine State. As it had in the past, the Army launched clearance operations in the region, driving out more than 650,000 Rohingyas to neighboring Bangladesh. It was widely reported as a humanitarian disaster, with the UN Human Rights Council describing the military operation as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Nearly a dozen of her fellow Nobel Laureates called upon Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to condemn those responsible for the Rohingya crisis. Malala Yousafzai and Desmond Tutu were among those who expressed their disappointment at her silence on the issue. Human rights organizations published satellite images of devastated villages in Maungdaw district. Recently, Human Rights Watch accused Myanmar of setting fire to more than 40 villages and Médecins Sans Frontières estimated that more than 6,700 Rohingya had been killed by security forces.

Among Western countries, Britain has been especially vocal in its criticism, even threatening to raise the issue at the UN Security Council. British institutions have been blunt in their condemnation of the state counselor for her silence on the brutal mistreatment of the Rohingya community in northern Rakhine. On the other hand, China, Russia, India and several Asian countries have supported Myanmar in votes at the UN.

In October, Oxford University’s St. Hugh’s College removed Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s portrait from its main entrance, while Unison, the UK’s largest trade union, suspended her honorary presidency. In Ireland, the Dublin City Council revoked her Freedom of Dublin award. Meanwhile, the U.S. government announced that at least one person from Myanmar would be targeted with sanctions.

Editor’s Note: The United States imposed sanctions on Maj-Gen Maung Maung Soe on Dec 21 for overseeing military operations in Rakhine State responsible for widespread human rights abuse against Rohingya civilians.

____________________________

U Phyo Min Thein: Challenger to the General

In January, when U Phyo Min Thein abolished Yangon’s old public bus system — notorious for its worn-out fleet and its unruly drivers and conductors — the move was heartily welcomed by city commuters. He introduced a new bus system known as YBS and imported 1,000 buses from China. But the reform was less than transparent; the tender for the Chinese buses was never made public.

When a Reuters story questioned the Chinese bus deal, he was furious. The chief minister filed a complaint against the news wire service with the Myanmar Press Council, claiming the story was factually incorrect. When the council asked him to explain exactly what was wrong, he could not provide the necessary information and the case was closed.

Despite his thin skin, U Phyo Min Thein has himself been annoying others, including one of Myanmar’s most powerful people — military chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing. At a forum for civil society organizations in Yangon in July, he said the commander-in-chief occupied a position equal to a director-general and that “there are no civil-military relations in the democratic era.”

The military took it as an insult and called on the government to “take necessary actions” against the chief minister. Two days later, U Phyo Min Thein sent a written apology to the military chief. He has not spoken about the military in public since.

____________________________

Nationalists: Preachers of Dhamma or Hatred?

In the face of a mounting crackdown this year by the government, Myanmar’s nationalist Buddhist groups are still on the move. It’s a relief to see no more of the bloody communal violence of recent years, yet nationalists have continued trying to raise tensions. Since the umbrella nationalist group Ma Ba Tha was banned in 2016, nationalists have been accusing the ruling NLD of failing to promote and protect Buddhism and favoring the human rights of other groups, especially Muslims. When the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army launched its attacks in northern Rakhine State in August, nationalists saw them as a threat to national security and interests. They interpreted the Rohingya issue as a matter of sovereignty.

At the center of Buddhist nationalism is U Wirathu, known for inspiring sectarian violence between Buddhists and Muslims. In March, the 49-year-old Buddhist monk was banned from delivering sermons because of his anti-Muslim hate speech. He and other nationalists have stood by the army and its clearance operations in northern Rakhine, calling the government “useless” and the army the “last resort when it comes to nationalism.”

For the government, the nationalists are a serious headache. It cannot contain them heavy-handedly because nationalist organizations remain popular — especially at the grass roots — by claiming the country’s Buddhist foundations are under assault and need to be protected. Given their anti-Muslim sentiments, the nationalists are also at risk of being politically manipulated by anyone who wants to make the most of the unrest. The image of a compassionate Buddhism, in which much of the country believes, has been distorted internationally by the nationalists into one that favors bigotry and antagonism.

____________________________

Dr. Zaw Myint Maung: President-in-Waiting?

With an ailing president in office, Myanmar needs someone who could take the place of President U Htin Kyaw in case of an emergency. Strongly tipped as the next person to occupy the position is Dr. Zaw Myint Maung, the chief minister of Mandalay, the country’s second-biggest city. The longtime NLD member endured lengthy prison sentences under the former military regime, won successive elections in 1990, 2012 and 2015, and is believed to be highly trusted by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Dubbed “Myanmar’s Duterte” for his resemblance to the Philippine president, the chief minister is also known for his peaceful crackdowns on anti-government protests. Apart from his ministerial position, the Mandalay native is one of the Secretariat members tasked with running the National League for Democracy now that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is constitutionally no longer the party leader.

____________________________

Sun Guoxiang: Interlocutor from China

China’s Special Envoy for Asian Affairs Sun Guoxiang has become a key player in peace negotiations between the National Reconciliation and Peace Center (NRPC) and the Northern Alliance. Throughout the year, he met with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Army chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing. While he hosted several meetings between representatives of the NRPC and Northern Alliance this year, few reports emerged about the situation on the ground in northern Shan and Kachin states. Recently, however, there have been clear signs that fighting has escalated between the Myanmar Army and Northern Alliance members in those areas.

China is aware that unless a solution can be found to the long-running ethnic conflict, there will be no stability along the shared border. As such, it has no choice but to deal with both the ethnic armed groups and the Myanmar government. While some people in Myanmar have criticized China for allegedly supporting the rebels, there is in fact no great affection in Beijing for the ethnic groups. However, China believes that it can use the rebel groups and the peace negotiation process to gain influence in Myanmar. Since the beginning of the reform period, the government in Yangon has engaged more with Western countries as opposed to its neighbor, causing China to feel ignored. However, China now has a chance to play an important role in Myanmar’s peace negotiations.

Despite not having a formal role or much official power in the peace process, Sun has proved to be an influential actor who could bring both the NRPC and Northern Alliance to the negotiating table. Some observers believe that China has been able to bring some stability to the border area despite not being able to fully restore peace. As a result, the Kokang region has seen some peace this year compared to last year, when the Myanmar Army launched a major offensive against the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). As long as fighting continues in northern Shan and Kachin, Sun and China will remain key players in Myanmar’s peace process.