The United Wa State Army (UWSA) began expanding its influence from northern Shan State along the China-Myanmar border into Thailand’s northern frontier provinces—Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai and Mae Hong Son—roughly three decades ago. This expansion followed the collapse of the Mong Tai Army (MTA) led by Khun Sa in 1996. The Wa leadership sought to establish a southern Wa entity, near the Thai border in Shan State, after having already secured Special Region 2 along the Chinese border.

Originally a relatively small force backed by Myanmar’s military as a proxy against Shan armed groups and as a means of controlling Thailand’s border areas, the Wa rapidly grew in strength. Narcotics became the cornerstone of their wealth—produced for domestic distribution in Thailand and trafficked globally. Over time, Wa-controlled territories also became hubs for other transnational crimes, including scam centers, illegal mining operations and a wide range of illicit businesses.

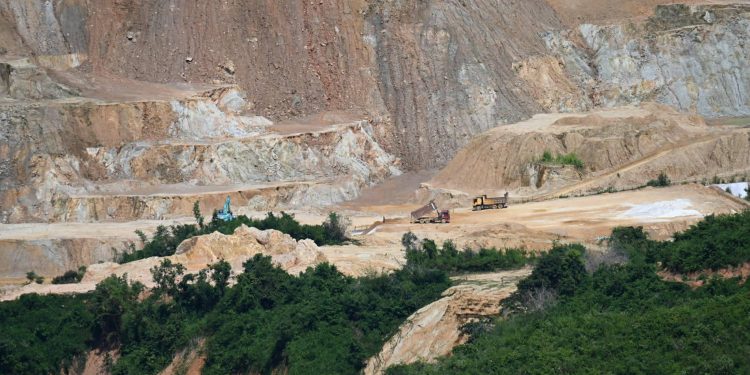

Today, the consequences are acutely felt by people in Chiang Rai and neighboring areas. The Kok, Sai, Ruak and Mekong rivers have become heavily contaminated due to illegal rare-earth and gold mining conducted by Wa forces in collaboration with Chinese gray-capital networks. In several locations, mining operations have taken place directly in river channels. At the headwaters of the Kok River in Myanmar’s Shan State, rare-earth and gold mines operate openly, releasing massive quantities of heavy metals into the waterways every day.

Myanmar’s military has largely failed to enforce the law. In some cases, mining operations are directly linked to the Myanmar army itself—including a large mine located near a small Hmong village in Mae Fah Luang district, Chiang Rai. In discussions as part of our field work, community leaders and Thai security officers all shared similar information: that the mines started around four years ago, with permission from Myanmar military leaders. There are confirmed Myanmar military posts In the area.

It is widely known that special arrangements exist between Wa forces and the Myanmar military, involving revenue-sharing from mining operations. Some of these payments reportedly flow across the border into Thailand, as part of long-standing informal agreements.

The enormous profits generated from drugs and illicit businesses have enabled the Wa to amass sophisticated weaponry and build formidable military capabilities. This has turned the UWSA into a serious security threat to Thailand—one that should not be viewed as less dangerous than challenges along the Cambodian border.

More troubling still is the Wa networks’ systematic infiltration into Thailand’s political and administrative structures. This mirrors the tactics used by Chinese gray-capital networks, which rely on patronage and bribery to access state power. Thailand’s entrenched corruption has made such penetration alarmingly easy.

Large numbers of ethnic Wa individuals have been able to obtain Thai citizenship with relative ease through corruption networks operating from village level up to departments within the Interior Ministry. Meanwhile, members of other ethnic groups who have lived in Thailand for 40 to 50 years remain stateless. Newly arrived Wa settlers, however, have been able to establish villages and secure Thai ID cards within just a few years.

One Wa village relocated to Chiang Rai as early as 1981. Today, most residents hold Thai citizenship, and village leaders have successfully run for political office.

Two years ago, I followed a case involving the installation of a fiber-optic cable stretching more than 10.5 km from a village in Mae Chan district, Chiang Rai, into a Wa military base in Mong Yawn, Myanmar. The operators claimed it was a water pipeline project, but parallel fiber-optic cables were clearly visible. The national security implications were obvious and should have prompted serious investigation.

I continued tracking the case, hoping to see decisive action. Instead, the issue quietly disappeared. A senior local figure later told me bluntly: “Don’t you know? They paid everyone off.” That comment explained everything.

The situation has since grown even more alarming. Wa networks are now attempting to embed themselves directly within Thailand’s power structure by fielding Wa-descended candidates in local elections—including subdistrict administrative organizations, provincial councils and village leadership positions. Armed with vast financial resources and supported by construction businesses used to curry favor with voters, these candidates have won repeatedly.

The most recent local election, last week’s subdistrict vote, followed the same pattern. And Wa networks have reportedly aligned themselves with powerful gray-capital politicians to send their representatives into the national legislature for the coming general election in February. With deep pockets and backing from influential national actors, they pose a serious challenge to Thailand’s political integrity.

The election outcomes in Chiang Rai therefore serve as a critical indicator of the direction Thai society is heading.

Will Thailand remain a country guided by moral foundations laid by previous generations—or will it slide further into becoming a gray-zone state, serving as a laundering hub for transnational criminal networks?

That is the question Thailand must now confront.

Paskorn Jumlongrach is the founding editor of a non-profit independent news outlet based in Thailand, www.transbordernews.in.th