A recent post on Tea Circle, “The Myth Myanmar Can Afford to Ditch,” argues that Burmese women are free, independent, and empowered. Alas, available data does not support such an argument.

A 2014 Study by the Asia Foundation found that 71 percent of respondents believed that men make better political leaders than women. An identical 71 precent believe that men make better business executives than women. The study found no differences between male and female respondents in holding these opinions.

Broader Burmese society reflects these views. According to the 2014 census, 270,000 women identified themselves as ‘employers’ – i.e., business owners, whereas 777,000 men identified themselves as business owners. Of the 100 largest Burmese conglomerates, only three are run by female CEOs. The census also revealed that for 7.2 million women, their primary job is ‘household work’, although this is true for only 270,000 men. On average, a working man earns 138,000 kyats per month; a working woman earns 110,000.

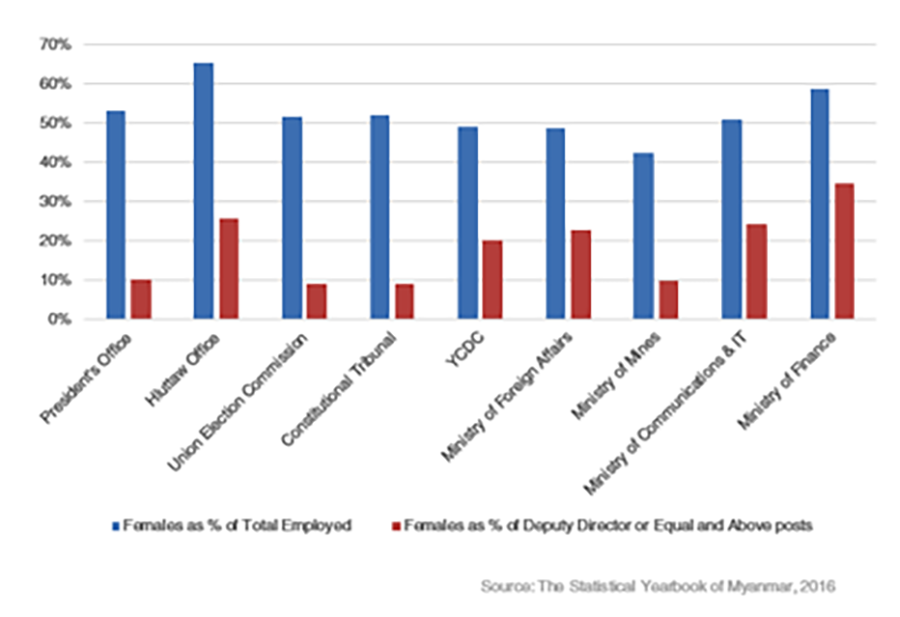

Women are excluded from top government jobs too. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi remains the only female minister. Only 14.5 percent of the Union Parliament (excluding the seats set aside for the military) are women – an improvement from the previous parliaments but still a long way to go before the country achieves a parity. Likewise, there is a scarcity of women in other government departments and branches.

At the President’s Office, women make up 53 precent of total employees, but only 10 percent of management level positions (management level is defined as Deputy Director or equivalent position and above). In the Union Election Commission, which singularly failed to discipline gender discriminatory language during the 2015 election, women make up 52 percent of total employees, but 9 percent of management. Figures are almost identical for the Constitutional Tribunal.

The Foreign Office, whose workforce is 49 percent women, drops to 23 percent women at senior levels. From 1967 to 2015, the country had no female ambassador. That year, Daw Yin Yin Myint was appointed ambassador to Germany, becoming the country’s second female ambassador ever, following Daw Khin Kyi, the widow of General Aung San, who served as Burmese ambassador to India from 1960-67. In the Ministry of Mines, 42 percent of the workforce is female, but 10 percent of its senior level positions are females. Female mining engineers are rare and in local culture, it is believed that if a woman were to enter a quarry or a mine, said quarry would stop producing minerals or collapse altogether.

At the Ministry of Education, 79 percent of its workforce is female and 76 percent of its leadership roles are filled by women – a parity to which other departments should aspire. However, at school-level – where an ordinary citizen first encounters social hierarchies as a child – the picture is less rosy. In elementary schools, 85 percent of the teachers are female, but only 63 percent of principals/heads of school are female. In middle schools, 90 percent of teachers are female, yet women make up only 71 percent of principals. In high schools, 82 percent of teachers are female, and only 59 percent of principals are female.

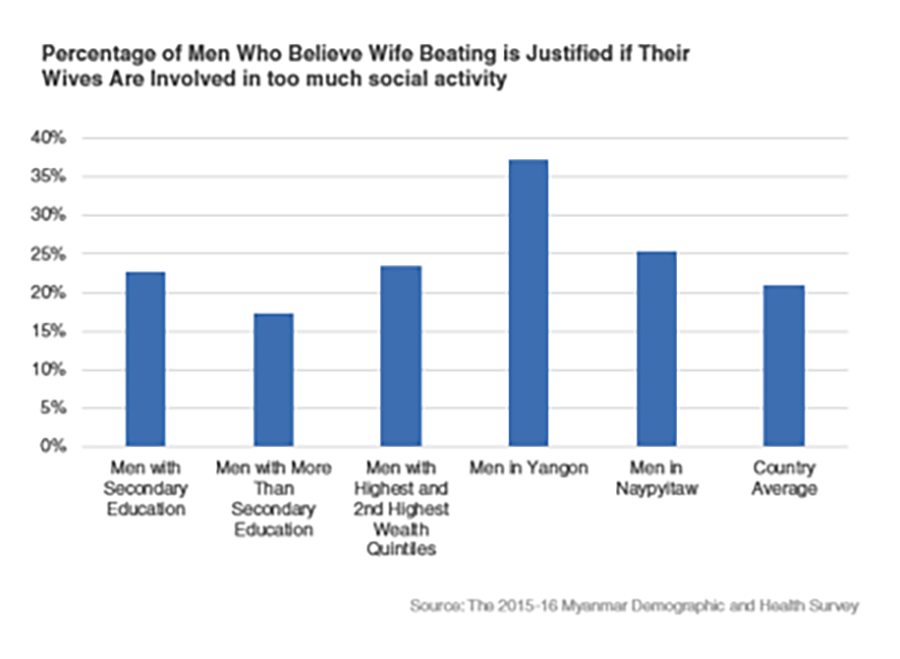

In addition to the lack of women in leadership roles, women’s position domestically is precarious too, where they play Nancy to the patriarchy’s Bill Sikes. In the 2015-16 Demographic and Health Survey, it was found that 51 percent of women agree that wife beating is justified under certain circumstances, a slightly higher percentage than the 49 percent of men who agreed. Men, however, are no paragons of virtue: 21 percent of men believed that wife beating was justified if their wives were “involved in too much social activity”. In Yangon, nearly two in five men held such a view.

Fifteen percent of women ages 15-49 have experienced physical violence, and three percent of women ages 15-49 have experienced sexual violence. However, only a small proportion of these violent attacks ever get reported. In 2016, there were 1,100 reported rape cases in Myanmar (and 700 cases in the previous year). Many rapes go unreported due to a culture of silence; a well-known Burmese saying, “Don’t make one shame into two,” exhorts against a rape survivor going public. Among women who have experienced physical or sexual violence and sought help, the majority sought help from family or neighbors. Only 0.9 percent of women noted they went to the police; a further 2.5 percent and 2.9 percent sought help from lawyers and social work organizations, respectively.

All these statistics are just the tip of an iceberg in a country where information is not readily available – information such as the availability of safe abortions. Even in rape cases, and in cases where the mother’s life is in danger, abortion is prohibited in Myanmar. Many suffer and perish in back-alley clinics.

As such, we cannot afford to ditch the ‘myth’ of female repression. We need to fight harder for gender equality, and as the original author noted, there is a lot to be hopeful about in Burmese society. The same Asia Foundation report cited above noted that 82 percent of respondents feel a woman should make her own choice when voting. The Demographic and Health Survey found high asset ownership rates, control over earnings, and participation in decision making for women. Labor participation among 20 to 24-year-old women is high at 72 percent.

From an economic standpoint, it makes sense to keep talking about and promoting women’s welfare and empowerment. Our internal assessments at First Rangoon show that if Myanmar increases female labor participation from the current 54 percent to 75 percent, the country’s GDP will increase by $7 billion (13.8 percent growth).

It should be a goal of the current government and parliament to maintain the high labor participation rate among the 20 to 24-year-old women, and amend the laws and institutions that disenfranchise and disempower them. Changing societal views and attitudes, not to mention religious and cultural teachings, will take time and generations. The institutional and legal reforms, however, can – and should – start immediately.

Born in Yangon, Shine Zaw-Aung studied International Relations at Stanford University, where he was an honors fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation. He co-founded First Rangoon, a consultancy, and contributed to the Myanmar Ministry of Foreign Affairs at MISIS. Shine is currently working toward his MBA at the University of Chicago.

This article originally appeared in Tea Circle, a forum hosted at Oxford University for emerging research and perspectives on Burma/Myanmar.