Colonial Burma has a strange hold on the Anglo-American imagination—it is a remote and exotic place where the British were not very successful in holding sway. British authority was routinely challenged by people in the forests of Burma who, the British felt, did not understand the beneficent “reason” inherent to their colonial project. From a British perspective the Burmese rebels and dacoits were unreasonable—they could not be bribed fairly and squarely with rubies, as the British expected.

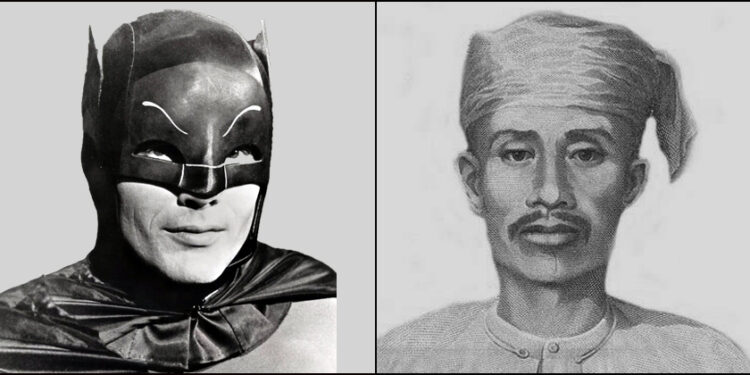

The character Alfred Pennyworth, the butler of Batman’s alter ego Bruce Wayne, experienced colonial Burma as a policeman in the 1930s. In the American 2008 Batman film The Dark Knight, Alfred described British frustration with the inability of Burmese bandits to reason.

Alfred was perhaps a member of the police units called on to control the revolt of Burmese hero Saya San in 1930-1932. Such experience apparently provided Alfred the basis for offering Bruce Wayne advice about why The Joker, a charismatic criminal nihilist sowing chaos, was impossible to reason with. The problem is, as framed in the movie, what do you do when your enemy does not respond to the same fears and incentives as “civilized” people?

Alfred presents to Batman/Bruce Wayne the same conundrum that bedevils the American military battling ISIS in the Middle East, or the Tatmadaw of the Myanmar military seeking to bend the Rohingya to their will. In their frustration, they come to believe that what their opponents want is not something logical, like money, and that their opponents are therefore incapable of reason.

Bruce Wayne: “I knew the mob wouldn’t go down without a fight, but this is different. [The Joker] crossed the line.”

Alfred Pennyworth: “You crossed the line first, sir. You squeezed them. You hammered them to the point of desperation. And, in their desperation, they turned to a man they didn’t fully understand.”

Bruce Wayne: “Criminals aren’t complicated, Alfred. Just have to figure out what he’s after.”

Alfred Pennyworth: “With respect, Master Wayne, perhaps this is a man that you don’t fully understand, either. A long time ago, I was in Burma. My friends and I were working for the local government. They were trying to buy the loyalty of tribal leaders by bribing them with precious stones. But their caravans were being raided in a forest north of Rangoon by a bandit. So we went looking for the stones. But, in six months, we never met anybody who traded with him. One day, I saw a child playing with a ruby the size of a tangerine. The bandit had been throwing them away.”

Bruce Wayne: “So why steal them?”

Alfred Pennyworth: “Well, because he thought it was good sport. Because some men aren’t looking for anything logical, like money. They can’t be bought, bullied, reasoned or negotiated with. Some men just want to watch the world burn.”

A few minutes later in the movie, Bruce Wayne asks Alfred what happened to the bandit in the forest:

Bruce Wayne: “The bandit, in the forest in Burma, did you catch him?”

Alfred Pennyworth: “Yes.”

Bruce Wayne: “How?”

Alfred Pennyworth: “We burned the forest down.”

Thomas Friedman used this exchange in a 2014 New York Times column. Friedman advocated intervention in Middle Eastern states that are “decent” as opposed to those facing ISIS and Boko Haram, who “Reason cannot touch… because rationalism never drove them.” Friedman recommends against “burning the forest down” to capture those who cannot be reasoned with and instead urges patience and containment, suggesting that it is best to wait until the virus of “barbarism burns itself out.” He points out that such groups cannot actually govern and the population will eventually seek an alternative.

Friedman’s view, however, is tough advice for both Batman and today’s militaries who still believe that triumphantly squeezing and hammering is the only way to exact compliance with “civilization.” The French used the tactic in their Algerian War (1954-1962) and the Americans in Vietnam (1962-1971) literally burned down Vietnam’s forests with the herbicide Agent Orange. The Tatmadaw’s “Four Cuts” campaigns after the 1970s used a similar “burn the forest down” strategy, employing cuts to basic services in areas occupied by the government’s enemies.

Indeed “burn the forest down” is still military doctrine for large powerful militaries frustrated with what they perceive as local intransigence, especially the rebels, bandits and nihilists who cannot be bribed with tangerine-sized rubies delivered by youthful Alfred Pennyworths, or suitcases of $100 bills delivered by CIA agents. But “burning the forest” operations are terribly violent in the short run and, while they result in short-term victories, such efforts can also fail in the long run. A few short years after hanging Saya San, the British were easily driven out of Burma, first by the Japanese and then by the Burma Independence Army of General Aung San.

Today in Myanmar, tactics of “burning the forest down” have been called “Clearance Operations” and led to the flight of 700,000 Rohingya to Bangladesh in 2017. Burning the forest down is used in war worldwide, in places like Palestine, Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq and Yemen, bombed or burned by superior militaries who assume rebels and a sullen population are easily subdued. In effect these militaries are casually assuming, as Bruce Wayne asserts, that “criminals are not complicated.”

But these strategies also still ignore the question about why “bandits” like Saya San tweaked the tail of the powerful British tiger in the first place. Assuming that they just “want to watch the world burn” ignores other motivations, like a desire to throw off the yoke of a tyrant and longings for self-determination.

Bribing bandits, burning forests and decapitating rebels brought some victories in British Burma for Alfred and his friends. But the British lost their war in Burma, as did the French in Algeria and Indochina, America in Vietnam and the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Friedman also takes Alfred’s reasoning a step further and describes how burning the forest has led to the creation of organizations like ISIS and Boko Haram. The same can be said of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), which launched coordinated attacks in Rakhine State in 2017. Such organizations are attractive to young nihilistic men who in desperation “just want to watch the world burn.”

As Alfred told Bruce Wayne, “You hammered them to the point of desperation. And, in their desperation, they turned to a man they didn’t fully understand.” This is perhaps the real lesson that Alfred should have drawn from his Burma experience. The powerful have the capacity to cross “the line” or to choose not to. But when they decide to squeeze and hammer a population to the point of desperation, the result may be more destructive than the problem they set out to resolve in the first place.

Tony Waters is Director of the Institute of Religion, Culture and Peace at Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand. He works with Burmese, Karen and other students in the university’s PhD program in Peacebuilding. He is also a professor of Sociology at California State University, Chico, and author of academic books and articles. He watched the Batman television show as a child. He can be reached at [email protected].

You may also like these stories:

Mobilizing Young, First-Time Voters Is an Investment in Myanmar’s Future

Ethnic Voters Face Disenfranchisement in Myanmar’s 2020 Election