The question is often asked: How much power and influence does China wield over Myanmar? The diplomatic answer is usually, “a certain amount”. But the offensive launched by ethnic rebels in northern Shan State in recent weeks puts the question of our giant neighbor’s clout in a new light.

The surprise attacks on Aug. 15 by an alliance of rebel forces were clearly prepared months in advance, despite ongoing ceasefire talks between the government, the military and rebel forces.

A series of coordinated attacks on that day by an alliance of three ethnic armed groups—the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Arakan Army (AA) and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA)—in five locations in Mandalay Region’s Pyin Oo Lwin and Shan State’s Naung Cho Township took the lives of 15 soldiers, police officers and civilians.

Calling themselves the “Brotherhood Alliance”, the groups are clearly attempting a large-scale disruption of trade and commerce along the two primary routes linking Myanmar with China. Over the past two weeks, they have blown up four major bridges along the main route to the two most important trade hubs on the Myanmar-China border.

Last week, The Irrawaddy reported that as a result of the attacks, “two major border gates in Shan State—in Muse (across the border from Ruili, in China’s Yunnan Province) and Chinshwehaw in Laukkai Township (part of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone)—have been shut down.”

The fighting has raised concerns over the feasibility of Beijing’s push to implement the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), part of its region-wide Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It also raised questions about the wisdom of the strategy embraced by both the Chinese and Myanmar governments to move ahead with the scheme before Naypyitaw has reached peace deals with rebels in the region.

The Irrawaddy’s correspondent Nan Lwin reported that, “Both China and Myanmar have claimed that implementing the CMEC will bring peace and stability to northern and northeastern Myanmar. Chinese think tanks often try to persuade people in Myanmar that the CMEC will support national reconciliation—one of the promises made by the Daw Aung San Suu Kyi-led government.”

But the surprise attacks have no doubt served as a wake-up call to top leaders in Naypyitaw to review the ongoing peace process with rebels in the north, while also calling into question China’s role as a peace negotiator.

China intervenes … but can it be trusted?

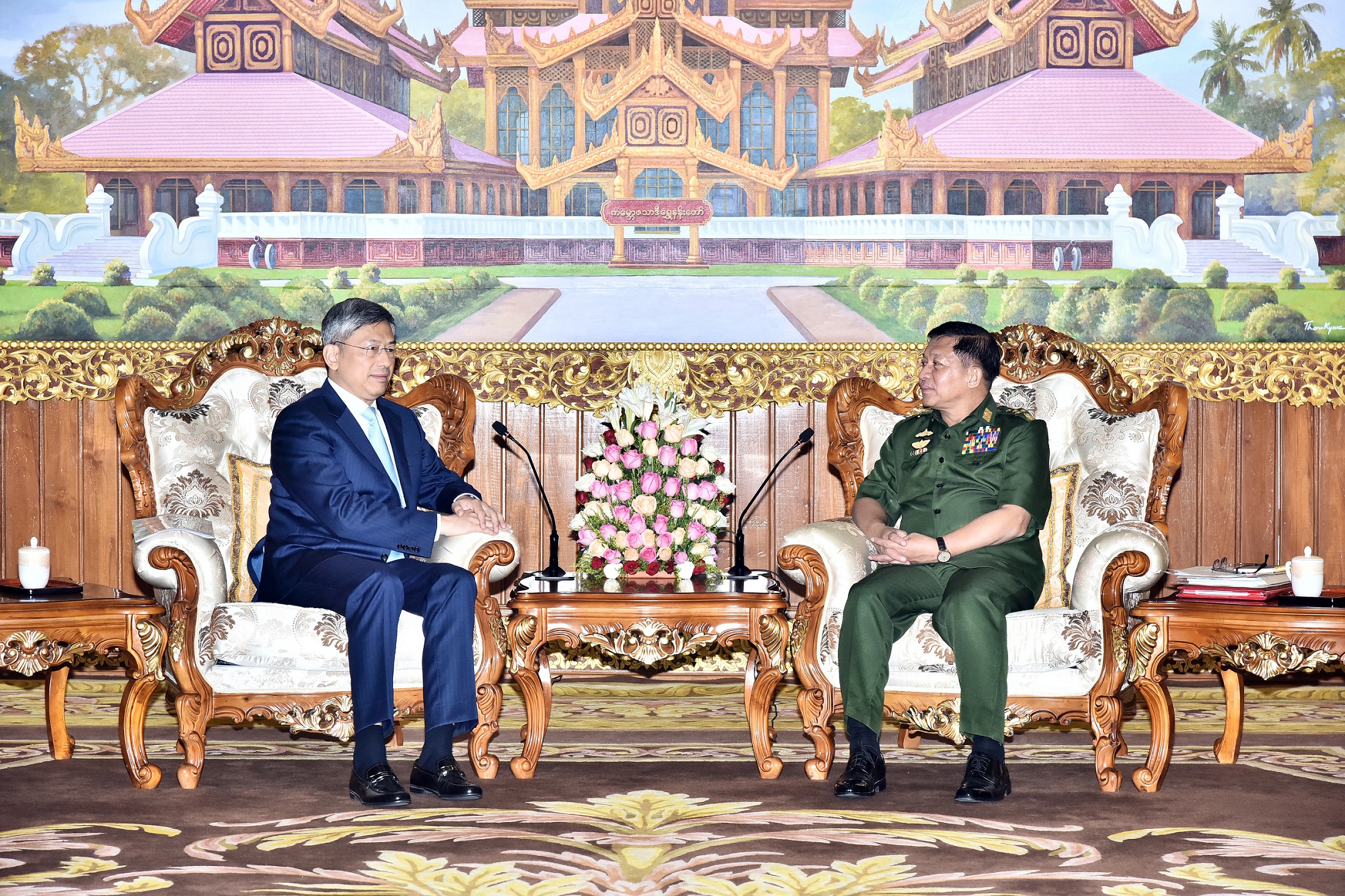

Chinese Ambassador Chen Hai held a meeting with Myanmar military commander-in-chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing a week after the attacks.

According to the Office of the Commander-in-Chief, Chen said China seriously condemned the recent violent attacks in northern Shan State and Mandalay Region’s garrison town of Pyin Oo Lwin, and “would continue to support Myanmar’s peace process and possible ways to improve peace dialogue” with ethnic rebel groups. The ambassador also proposed several venues for ceasefire talks between the rebel forces and the military. It is believed that Keng Tung in northern Shan State has been selected, and that the commander-in-chief approved the venue.

Pyin Oo Lwin—a former British hill station once known as May Myo—is officially designated a “white area”, meaning it is considered a secured zone safe from attacks by insurgents. The army admitted during a press conference last week that the attacks took it by surprise.

The ethnic rebels who launched the attacks haven’t confirmed their attendance at the talks yet, but the army seems keen to hold a meeting. An army spokesman said bluntly during the press conference that it is up to the rebels to decide whether they want to keep fighting or enter talks.

After the attacks, the Myanmar army responded by sending more troops to the north and pushing the rebels back to the jungle and farther north. Lieutenant-General Moe Myint Htun, who has served as a commander in Naypyitaw in the past, was tasked with quelling the rebel offensive.

Before Chen’s meeting with Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing on Aug. 19, the Chinese Foreign Affairs Ministry condemned the three rebel groups’ offensive and the ongoing clashes in northern Shan State.

But the message from army headquarters in Naypyitaw to China was that a condemnation was not sufficient, as the military believes that powerful rebels—in particular the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Myanmar’s largest armed rebel group, which has received backing from China—were behind the attacks.

Chen then flew to Naypyitaw and held a meeting with Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing.

Before Chen’s meeting in Naypyitaw, aware of the Myanmar leaders’ views, Sun Guoxiang, Chinese Special Envoy for Asian Affairs, invited officials from the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC)—which is led by the UWSA—to Kunming.

The TNLA, AA and MNDAA are members of the FPNCC. (According to observers familiar with the ethnic armed groups in Myanmar, the Kachin Independence Army, another member of the FPNCC, is keeping its distance from the recent conflict. Does this point to a split in the FPNCC? The Kachin and the Wa have the most powerful armies in the north, but are not getting along.)

The Chinese envoy reportedly asked insurgent groups to send only top-level leaders with decision-making authority to the Kunming meeting. The Wa, Kachin, Kokang, Arakanese and Ta’ang sent top-ranking leaders to meet with Sun. The rebels later said that China pressured them to stop fighting, though clashes continued on the ground. Is this a sign that the rebels aren’t listening to China?

There are lingering suspicions as to who was behind the attacks.

Some reports suggest that the recent clashes involved a contingent of 200 to 400 rebel fighters, with the largest group coming from the TNLA.

During the attacks, the Myanmar Army intercepted communications between rebel forces in which several rebels were heard speaking in Chinese. Some ethnic rebel forces such as the MNDAA and Wa communicate in Chinese.

There have also been unconfirmed reports that foreign fighters were involved in the recent attacks. The generals in Naypyitaw remain tight-lipped on the subject, but one can sense that animosity and mistrust toward China is growing among Myanmar’s generals.

In February 2015 intense fighting erupted between the Myanmar Army and Kokang rebels belonging to the MNDAA around Laukkai, the administrative capital of the ethnic Kokang region of Shan State, near the Chinese border. The clashes lasted for about two weeks. The army finally pushed the rebels back but there were heavy casualties on both sides. The rebels retreated to the Chinese border.

Both local and foreign media reported on China’s role in the fighting in Laukkai.

General Myat Htun Oo, who is now chief of the Myanmar military’s general staff, claimed at the time that “Chinese mercenaries” had joined the ranks of the MNDAA, but U Aung Min, then the government’s chief peace negotiator, said China was not responsible for the clashes.

In the wake of the latest clashes involving northern rebels, Myanmar officials, including top army leaders, are wary over China’s role and its influence.

China’s priority is the success of the transport and infrastructure projects it is developing with Myanmar as part of its region-wide Belt and Road Initiative. However, the rebels in the North have now demonstrated that without them the projects cannot go ahead.

Before the latest outbreak of fighting, Myanmar’s military leaders may have been hoping that stability in the north this year would buy them time to crush the insurgency in northern Rakhine. But this is no longer possible. The military will be stretched as it sends troops to counter the rebel offensive in northern Shan State. It seems the rebels are determined to keep pressure on both fronts—northern Rakhine and northern Shan. The military was perhaps also hoping that China would keep the rebels in the north under control. But this has not come to pass, either. Unlike the battle in Laukkai in 2015, the rebels have brought their fight against the Myanmar military deeper inside Shan State, and away from the Chinese border.

At an earlier meeting with Sun, Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing reportedly provided information, including photographs, on grenade launchers, mines and other weapons seized during recent clashes in northern Rakhine State. The weapons are believed to have been supplied by, or manufactured in, China.

China’s many interests in the region contribute to a growing sense of mistrust on the part of the military, complicating Beijing’s offer to mediate the conflict in Myanmar.

You may also like these stories:

Rebel Strikes Cast Shadow on China’s BRI Projects in Myanmar

Myanmar Military Says It Will Hold Peace Talks With Ethnic Armies in Shan State

Ethnic Alliance Says 30 Myanmar Army Troops Killed in Northern Shan