YANGON — More than 1,500 Twitter accounts posting provocative hashtags and messages commenting on the violence in Rakhine State were launched days after the Aug. 25 attacks.

Many of the accounts were posting identical tweets, had screen names ending in digits and used the default Twitter profile image—all bot-like activity common in automated accounts, said Raymond Serrato, a digital researcher and analyst who works on governance and democracy in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan.

Serrato, who retrieved the data using Twitter’s Search API, said from August 23-30, there were 13,137 tweets that included the hashtag #Bengali, a term used by many in the government and Myanmar to describe the Muslim Rohingya, implying they are interlopers from Bangladesh.

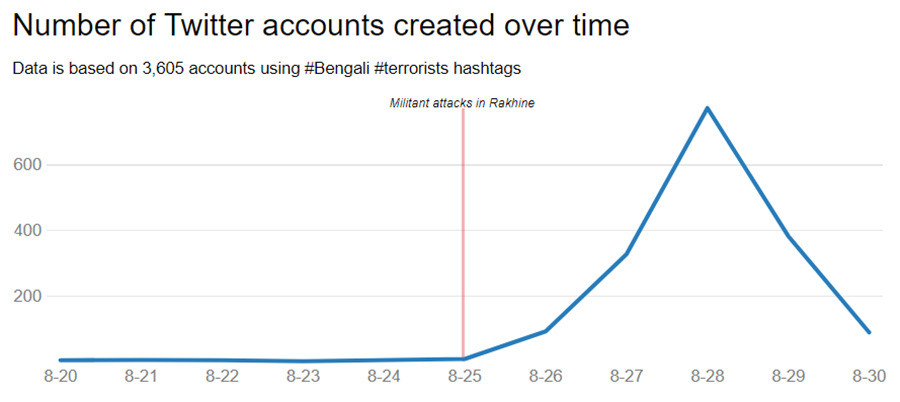

These tweets came from a total of 3,605 users, with an average of three tweets per account. Of these accounts, 1,647 were created in the days following militant attacks on police stations in northern Rakhine that triggered ethnic violence, an army crackdown, and the exodus of tens of thousands of people in the region.

Serrato gauged the tweets’ content by analyzing the sentiment of words found in them such as “kill” and “extremist.” Nine accounts posting such terms were created on Aug. 25, with the number rising to 93 on Aug. 26, 328 on Aug. 27, and 773 on Aug. 28 before sloping to 383 on Aug. 29.

Similarly, Serrato noted an increase in new bot-like accounts: three on Aug. 25, 22 on Aug. 26, 77 on Aug. 27, 191 on Aug. 28 and then 96 on Aug. 29.

“I also discovered other accounts with strong bot-like traits, but which are harder to detect using machine scanning, such as accounts that use screen names like @6fb55a2399a042b,” he said over email.

“All of these accounts also posted duplicate tweets, often only changing the images associated with them or one or two characters in the tweet’s text. Spellings sometimes differ from tweet to tweet too, which hints at human users curating the accounts.”

The following tweet had the most cloned posts from separate accounts in the data—57 altogether: “Extremist #Bengali terrorists kill six innocent Hindi in #MYANMAR, August 27 #UN”

The government declared Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) a terrorist organization soon after the group’s early morning offensive on 30 police stations and an army base on Aug. 25, which it stated was a step toward restoring the rights of the stateless Rohingya.

This post from the official page of Myanmar’s State Counselor received the highest number of retweets—841—in the data, although the tweet has since been deleted: “RT @MyanmarSC: #Extremist #Bengali #terrorists torch their homes Read More==> https://t.co/TQrB2bDMEn https://t.co/4UMgVXEAGq).”

Out of the accounts, 527 have the default Twitter profile image and 505 accounts contain screen names ending in a sequence of eight digits.

“Both these traits are strong indications of bots, but can also point to the setup of the many accounts in haste, where users select Twitter’s suggestion of a string of numbers after the name,” said Serrato.

“It’s impossible to know who could be behind the setup of these mass accounts. All the tweets are in English, which strengthens the argument that they are intended primarily for an international or Western audience,” he added.

Serrato said he was not aware of accounts posting views against the government’s stance in a similar pattern.

Taking to Twitter

In a country where Facebook reigns supreme, with an estimated 14 million users out of a population of nearly 53 million, the terse format of Twitter is yet to catch on.

But in the wake of the recent attacks, some social media users are eyeing the social media site as the next platform to spread their views.

Digital marketer and blogger Maungthargi, also known as Khing Soe Aung, posted on Facebook a step-by-step guide on using Twitter, including instructions to follow and retweet the official State Counselor account, and to use hashtags #Bengali #Myanmar and #Stopterroristssupport.

The guide, which amassed 1,000 likes and nearly the same amount of shares, also accused those connected with the Rohingya community of spreading fake videos, asking users to report them.

“When people around the world only see fake news about the Rohingya case posted by the Rohingya, they will misjudge the situation. That’s why we are encouraging Myanmar people to use Twitter, and to let the world know the truth,” Maungthargi told The Irrawaddy.

On reports of automated Twitter accounts, he added, “That is right. Those fake accounts spreading hate speech and arousing people’s anger are absolutely worth being reported.”

Rakhine Information Wars

Yangon-based independent analyst David Matheison described the influx of seemingly pro-government Twitter accounts in recent days since the ARSA attacks as a “disturbing escalation in the social media wars around Rakhine.”

“Where this activity is stemming from is still a mystery, but it could indicate pro-government social media activists expanding their presence on Twitter to counter the ARSA messaging,” he said, adding that the social media platform has typically been the domain of foreigners in Myanmar.

Mathieson described the tweets as “racist propaganda slogans” that are “a worrying development that will render marshaling the facts of the complex conflict in Rakhine even more difficult.”

If Twitter becomes the social media battleground between ARSA, Rohingya activists and the government and their supporters, either in society or the military, “then truth on Rakhine has all but ended,” he finished.

Yangon regional lawmaker Nay Phone Latt, who has campaigned against online hate speech, cannot imagine Myanmar’s public flocking to Twitter when they are comfortable posting in the Myanmar language on Facebook.

But he welcomed a recent change to the name of the State Counselor Office Information Committee’s Facebook page to the “Information Committee” on Aug. 29.

“Some of the news was biased and not the opinion of the State Counselor,” he said. “They did not obey a good standard. Sometimes they posted things they should not have.”

The State Counselor’s Office Facebook page has previously dismissed independent reports of rape and atrocities in Rakhine. Created following militant attacks on border guard posts in the state in October 2016, a government spokesperson announced on Wednesday the page had been changed to show it represents the military, home, foreign and border affairs ministries, and the President’s Office as well as the State Counselor’s Office.

People must be careful about the words they use, said Nay Phone Latt, adding that terminology such as “Islamic State” should not be used to describe the situation in Rakhine.

“Some groups who want to create violence use the Rakhine issue and try to ignite the flame in other places,” he said. “Only one word can make a big problem.”