MYITKYINA, Kachin State — All Aike Yoon wants is to go home. But he can’t.

The 40-year-old is currently living in Thagara Monastery, which serves as a makeshift internally displaced persons (IDP) camp in Waingmaw Township, Kachin State. He has six children and hails from the village of Sam Paing, 40 miles from the Kachin State capital, Myitkyina. Sam Paing once was home to some 40 households, and every villager owned both buffalos and farmlands. But in 2011, when war broke out between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Burma Army, Sam Paing and four other nearby villages were caught in the crossfire and burned.

Thursday marked the fifth anniversary of the outbreak of fighting that ended nearly two decades of relative peace.

Aike Yoon has been living for five years in Thagara camp like the other 480 IDPs residing on the monastery grounds. It is not easy to visit his village, but sometimes he goes back to clear trees and bushes around his house. First, he needs to get the approval of the IDP camp management committee. Then, he needs the go ahead from the Burma Army’s commander to enter that area.

The military command post is based in the middle of Aike Yoon’s village, and any villager returning is watched closely the whole time they are back home.

There are many military checkpoints between the camp and his village, and signs warn of landmines beside the highway between Myitkyina and Bhamo.

While his home is now a burned out husk, he still would prefer to return and repair it rather than live elsewhere. In the camp, Aike Yoon remains unhappy because his family’s current living quarters are cramped and uncomfortable, and they have to abide by the camp’s rules and regulations.

“If there was no fighting, I would like to return home because I have farmland and cattle,” said Aike Yoon. “But there are landmines around the village, so even if there is no fighting, we still wouldn’t feel safe.”

Relief Dries Up

United Nations (UN) agencies and international relief organizations provided rice and cooking oil as well other essential supplies to Kachin’s IDPs for the last four years. But all of that changed in January. The UN and other organizations started giving only financial assistance instead of rice.

Now the relief organizations give 300 kyats (US$0.25) per day to each IDP, which is not enough to buy the amount of rice the UN and other organizations had been providing. Additionally, they have to buy cooking oil, salt and fish paste to make their food.

“What can we do with such a small amount?” said Aike Yoon. “We have to take what they give us whether we like it or not.”

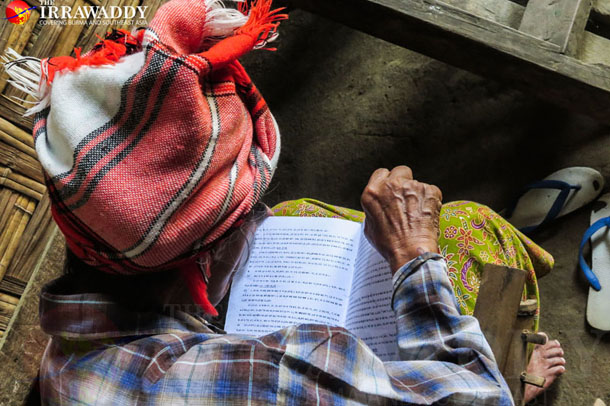

Aike Yoon’s family is surviving by earning a small income from making amber handicrafts and decreasing their daily expenditures. His three sons are attending middle school but they are not sure if they will be able to keep their children in school because the aid cuts have had a major impact on the family.

The Irrawaddy contacted the World Food Program, which had been the main supporter of many of the Kachin-based IDP camps, but a representative in Rangoon declined to answer questions about the funding cutbacks.

When Will They Return?

La Roi, the Program Director for the Kachin Baptist Convention (KBC) Bhamo, a local relief organization, said he was told by some aid agencies the financial cuts were not just targeted at Burma, but have also affected programs worldwide.

“‘When will the IDPs return home?’ some international non-governmental organizations asked me,” La Roi said. “There is no fighting now, so the IDPs can go back home now.”

Dangers remain, however, leaving many IDPs reluctant to return home.

Dangers remain, however, leaving many IDPs reluctant to return home.

The KBC director said that an IDP was killed by a landmine after returning home earlier this year. And fear of the Burma Army runs deep.

An IDP living at Robert Church, Inn Khu Nam, said, “I have known many young Kachin girls who were raped by Burmese soldiers. I am scared of them. I will never return until they withdraw from our village.”

Behind the Scenes

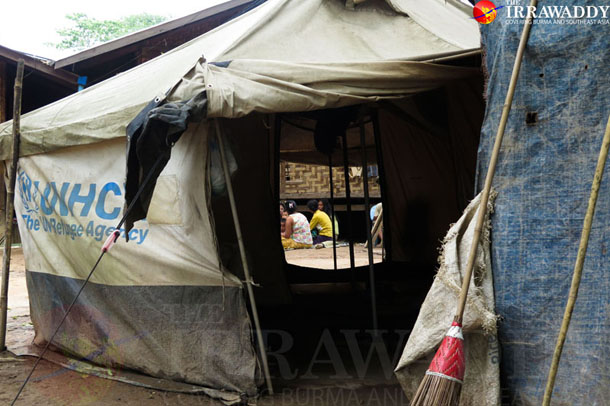

The KBC in Bhamo, 100 miles southwest of Myitkyina, has delivered over US$6 million to 12 IDP camps home to more than 10,000 people. In partnership with UN agencies, the KBC distributed food, built shelters and provided healthcare to the camps.

But some IDPs do not even have the luxury of living in a UN-supported camp. Robert Church in Bhamo houses 3,600 people, with whole families squeezed into 60-square-foot rooms.

The KBC’s La Roi said many problems have arisen recently, and the financial cuts have exacerbated the situation. Some middle and high school students have dropped out and are working at construction sites, phone service shops, restaurants, hotels or tea shops to help support their families.

Some have even gone further afoot, with the promise of higher-paid jobs in factories and on banana plantations inducing them to cross the border to China illegally.

La Roi said, “This is becoming a more significant problem.”

During the day, the IDP camp on the Robert Church grounds is virtually devoid of men, most of whom have gone off to work in jade mines or on construction sites.

But the IDPs’ struggles do not end in the camps. Often, they face discrimination from local communities.

Even at the government-run school, some teachers have reportedly made a separate classroom for IDP children and sometimes the teachers do not allow IDP students to use the same bathroom as the local students. This discrimination is yet another factor encouraging the students to drop out of school.

“Some people say we Kachin people are lazy and have adopted the behavior of beggars,” said La Roi. “I get really upset when I hear things like that.”

The Amber Business

Khat Cho, one of the IDP camps in the Kachin State’s Waingmaw Township, has been home to approximately 500 IDPs since the conflict started. Fighting has been intense in Waingmaw due to the presence of natural resources like amber and gold.

While it is widely assumed that the IDPs are all ethnic Kachins, there are actually many Shan, Burman and Arakanese people who were working in mines when the fighting forced them from their homes.

Htwe Htwe Myint is Burman and a mother of two currently living in Khat Cho camp. Her family receives 36,000 kyats a month from World Vision, a US-based Christian charity, but that is not enough to cover daily expenses. Meanwhile, her husband has struggled to find work on construction sites or rubber plantations.

“We are now dependent on the extra income we earn [in addition to the aid],” she said. “If we can’t earn any more money we will be in trouble. The price of rice is going up.”

Htwe Htwe Myint’s family makes beads, necklaces, bracelets and rings with colorful amber stones, work that requires them to buy raw materials from a nearby amber-rich region.

Htwe Htwe Myint and other craftspeople sell their products to shops in the cities Waingmaw or Myitkyina. The families earn some money from their handicrafts, but the products’ prices have been dropping over the past few months. The artisans claim the shop owners pay them low prices for their wares, despite the fact that they export the amber products to China illegally and make sizeable profits.

Of Khat Cho IDP camp’s 90 households, almost 80 percent make amber handicrafts, said Khin Maung Shwe, leader of the management committee for the camp.

Livelihood programs are run by the WFP, Oxfam, International Committee for the Red Cross and World Vision, but there are limitations. The IDPs have to create a “business” of four to five families and focus on jobs like livestock raising, food vending or tailoring. They also are required to submit a detailed business plan to the relief organizations. If the business plan is approved, each family would receive around 50,000-60,000 kyats (US$42-$50).

New Programs, New Problems

According to the KBC, 32 camps are located in Waingmaw and Myitkyina townships, serving more than 14,000 people.

Khong Dau, the head of Maina IDP camp, the largest camp in Waingmaw Township, acknowledged that international aid dropped off in early 2016, and described some of the new aid programs as complicated and ineffective.

The decreased financial aid and change in payment method has had a negative impact on the IDPs, he said, adding that human trafficking, drug dealing and other social problems would appear at the camp if the international relief organizations keep limiting aid.

More than 2,000 people from 30 different villages live in Maina camp. They became homeless after their houses were burned down during fighting in 2011.

Lu Mai, a resident of Maina, said, “We would like to get rice and cooking oil instead of cash.”

Hoping for Peace

The Irrawaddy also visited Mai Kaung IDP camp of Man Si Township, located so close to the conflict zone that sometimes the residents can hear explosions from the blue-hued mountains only a few miles away.

La Byart Khun, a 50-year-old mother of five children, is currently living in Mai Kaung IDP camp. Reflecting the sentiments of many people living in the camps, she said requesting food and cash from the organizations is humiliating.

“We would not ask for aid from them if we could safely return home,” she said. “I’m waiting for that moment.”

Naw Maing, an IDP who is head of the management committee for Mai Kaung camp, said they frequently hear about peace talks but see no results. Fighting between the KIA and government troops is still intermittent around the nearby Mt. La Htaw Phone.

“I have heard that the government peace negotiator didn’t answer the questions posed by the KIA’s official, Gen Gun Maw,” he said, referring to last week’s meeting between the National League for Democracy peace envoy, Dr. Tin Myo Win, and representatives from ethnic armed groups in Chiang Mai, Thailand. “So I don’t think we’ll have peace.”

Naw Maing urged both sides to prioritize removing landmines and withdrawing their forces from the villages.

“We are scared of both sides,” he said. “They have weapons, but we are empty-handed.”

While almost every IDP dreams fervently of going home, one 71-year-old widow has accepted what she expects to be her fate.

Inn Khu Nam has already decided that she will spend her last hours at Robert Church if the Burma Army soldiers never withdraw from her village. She said she has been spent almost five years in a tiny room, but at least she can find peace at the church.

“Dying in a churchyard is much more honorable than dying in a war-torn place,” she said.