LEDA, Bangladesh — Rohingya Muslim refugee Ali Hasan is desperately looking for a bride for his 14-year-old son, jailed last year in Bangladesh for carrying the popular drug yaba. He hopes the girl’s family would pay the $620 needed for Mohammed Hasan’s bail as dowry.

Police arrested Mohammed with 5,000 pills of yaba, as methamphetamine is widely known in Asia, last June. His elder brother, Izzat Ali, was arrested a few months later with 200 pills and sent to prison.

Bangladesh says the influx of Rohingya fleeing Buddhist-majority Burma is partly to blame for soaring methamphetamine use in its cities. But many Rohingya say their young people are being pushed into crime because they cannot legally work or, in many cases, access aid.

Ali Hasan fled Burma three decades ago and his sons grew up in an unofficial camp in Leda, a 15-minute drive from the Naf River separating Bangladesh from Burma.

It is not uncommon for Rohingya families to arrange marriages while the couple are still in their mid-teens, and the 60-year-old does not think the fact Mohammed is in jail awaiting trial will be an issue, so common have such brushes with the law become among the refugees.

“We’re looking for a bride for him so that they can pay the dowry in advance,” he said. “People know that he was lured into it and he had no wrong intentions, so I don’t think getting a bride will be difficult.”

Rohingya Muslims have been fleeing apartheid-like conditions in northwestern Burma, where they are denied citizenship, since the early 1990s, and there are now more than 200,000 in Bangladesh. More than 70,000 have flooded across the border since October, escaping an army crackdown.

Local Resentment

Consumption of yaba—Thai for “crazy medicine”—is booming in Bangladesh. Seizures alone jumped more than 2,500 percent to 29.4 million pills last year compared with 2011—and the business is worth an estimated US$3 billion annually.

Police and government officials say the stateless Rohingya refugees, who cannot easily be traced, are the traffickers’ preferred mules.

The authorities have cited a growing drug problem as one reason for pushing ahead with a controversial scheme to move thousands of refugees from their border camps to an undeveloped island in the Bay of Bengal.

“The local population and local leaders are extremely unhappy about this influx,” H.T. Imam, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s political adviser, said in Dhaka. “They displace laborers by undercutting locals. The yaba trade is flourishing due to them.”

He did not provide any data about the refugees’ involvement in the drug trade.

Residents of Cox’s Bazar, the coastal district neighboring Burma where most of the refugees live, are now holding public meetings and rallies in support of the refugee relocation plan.

Sanmaraz, a 35-year-old Rohingya woman living in Leda, arrived from Burma two decades ago. Her husband, Amanullah, is now in jail awaiting trial on charges of carrying yaba. She says he was “framed” by local villagers.

“Bangladesh has given us shelter, but the local people don’t want us here,” she said. “They want to harm us; they want to chase us away.”

Only the 34,000 refugees living in two official camps are eligible for international aid. In places such as the Leda Unregistered Rohingya Refugee Settlement, where Ali Hasan and Sanmaraz both live, there are few means of support.

As a result, many end up working as drug carriers, while some women are lured into the sex trade, said Afruzul Haque Tutul, a senior police officer in Cox’s Bazar.

Rukina Begum, 35, said she was persuaded to join another Rohingya woman carrying 1,000 yaba pills on a bus by the promise of work for her 11-year-old son.

“If only I had money I would never have sent my young son to work anywhere, and this would not have happened,” said Begum, who was out on bail after spending eight months in jail.

Bangladesh insists the Rohingya, though undocumented, are Burmese citizens and must ultimately return.

“We cannot allow citizens of Burma to work here,” said Imam, the prime minister’s adviser. “There are several local committees under the district administration to provide relief to them.”

Surging Yaba Demand

This month Reuters was taken to a tin shed by a canal in the Leda camp, where a 19-year-old youth wearing a blue T-shirt and longyi took orders for yaba from two customers seated on a mat.

The youth, who fled to Bangladesh three years ago, said he buys 20-50 yaba pills from a local villager every day after tasting one or two himself for quality.

Bangladesh consumes an average of 2 million such pills a day, estimated two officials at the Department of Narcotics Control (DNC) in Dhaka.

Each pill retails for around 300 taka ($3.75). The same pill can be bought for around 60 taka in Cox’s Bazar. Rohingya “mules” can earn 10,000 taka for transporting 5,000 pills to Dhaka and other urban centers, the officials said.

“Our data shows that the majority of the carriers are Rohingya,” said police officer Tutul, but declined to share specific numbers.

A DNC mobile court has convicted 15 refugees in the past six months.

But the Rohingya mules are only a small cog in the yaba supply chain.

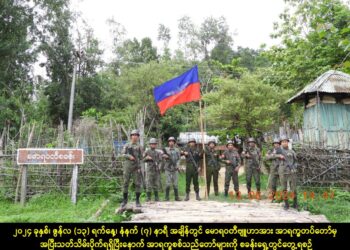

From negligible yaba sales a few years ago, Bangladesh has become a big market for traffickers who source the drug from factories in lawless northeastern Burma, according to Jeremy Douglas, regional representative of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

“Whatever has been coming is growing very, very fast,” he said. “But it’s much bigger in Burma. Internal demand there has been very carefully cultivated and developed by organized crime groups. They have been trafficking inside the country and they have been pushing the product fast, including towards Bangladesh.”