RANGOON — Wyne is an award-winning director famous for his films depicting relationship drama; the movies are popular among young audiences and the film censorship board alike. But when he tried to test out a new genre, he had no idea how hard it would be.

In 2014, Wyne submitted the synopsis of his planned feature film “Letter to the President” to the censorship board.

The plot does not seem particularly inflammatory: A young man is accused of a murder that was really committed by the son of a government minister. His grandmother tries to help him but later dies under mysterious circumstances. Then, her spirit writes a letter to the president and tries to enlist the help of various people to deliver it. Ultimately, the letter ends up in the president’s hands.

The censors were not happy. First, they tried to convince Wyne to change the name of the film. He refused. Then they suggested he change the character of the minister’s son to the “son of a crony.”

“It was impossible for me to change the character I created,” Wyne said. “It took me about two to three years to work on this script! It was just disappointing,” he said, adding that he wanted his character to portray people who abuse authority. To date, the censorship board has refused to grant approval for the film.

The film censorship board, officially known as Motion Picture Classification Board, is chaired by the director-general of the Ministry of Information’s Motion Picture Development Branch (MPDB) and made up of 15 representatives from different associations including the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (MMPO), the Myanmar Music Association, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, the Attorney General’s Office and the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs.

Before 2011, the regulations that were used to scrutinize the content of films and movies covered 10 principles, ranging from politics, religion, and goodwill among ethnicities to “good” personal morals. The national film censorship board aggressively controlled the whole industry until the end of 2011 when four themes—promotion of good personal morals, an emphasis on crime reduction, the exclusion of obscene presentations and a prohibition on the portrayal of child abuse—were removed.

Regulations ‘Killed’ Creativity

Burmese director Wyne argues that filmmakers who have long worked under the country’s strict censorship practices can not help but continue to self-censor while making films; these regulations, he claims, have “killed” their creativity.

“Most of the time, I try to make romantic movies that are within the bounds of censorship regulations and avoid controversies,” he said. “But when I try to make one film that reflects the realities in our society, I didn’t get approval from the censorship board.”

There is no need for any filter between filmmakers and the audience, he said.

“The audience will punish us if we make bad films. We will face failure when the audience stops supporting us. We can’t forget that the audience is always judging our films,” Wyne told The Irrawaddy.

Wyne publicly criticized the long-standing film censorship system in his 2011 30-minute film entitled “Ban That Scene,” which portrays censorship board members cutting movie scenes about corruption, poverty and street fights.

“If foreigners watch this film, they’ll think [Burma] has beggars. Beggars may exist in real life, but not in this movie,” explained one character who played the role of such a board member in the short film.

“When we want our films to reflect actual things that are happening in our society, censorship is something we can not overcome,” Wyne explained. “Art must be independent. There shouldn’t be any boundaries.”

Dictatorship and Bell-Bottoms

While it would be easy to lay the entirely of the blame for censorship on the military regimes that ruled Burma for nearly half a century, the history of censorship in Burmese cinema actually dates back to the colonial era. Some films dealing with social ills and corruptions were banned by the British administration, but Burmese cinema culture continued to address political themes after World War II and the country’s 1948 independence from the British empire.

Political repression, however, took a sharp turn for the worse after the 1962 coup as the country suffered under Gen Ne Win’s so-called “Burmese Road to Socialism.” From then on, the entire film industry was forced to make movies that not only obscured reality, but also praised the military government.

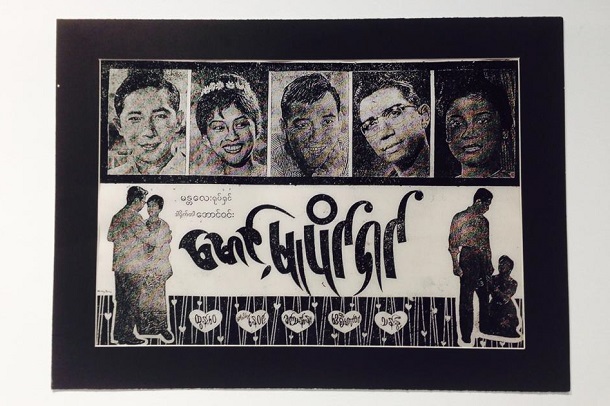

A booklet issued in 1974 for the Burmese Academy Awards (1972-73) included a list of censored scenes from films that were produced during those two years.

Scenes in which an actor sporting long hair sang, an actress was singing in a dress and an actor was wearing bell-bottoms were described as being “against the Burmese culture” and were cut. Couples touching cheek-to-cheek on camera were deemed “shameless.”

Five-time Burmese academy award winner Kyi Soe Tun told The Irrawaddy about how a film from the 1980s fell victim to the censorship board’s “cultural standards.”

“Thingyan Moe,” directed by Maung Tin Oo, is about two generations of love stories in Mandalay, centered around the city’s water festival—Thingyan in Burmese. The problem, however, was not with the plot or the movie’s message.

In standard Burmese, the word for “I” is gender-specific—men say kyadaw and women say kyama. But in the Mandalay dialect, women and men both say kyadaw. And that was a problem.

“They banned the usage of kyadaw in the film and told the director that girls should not say things like that,” Kyi Soe Tun said. “But it’s a part of the local identity. I think it’s great for a film to have such an identity. That makes it authentic.”

Fear and Freedom of Art

The censorship regulations in Burma today are based on those established following the pro-democracy movement of 1988, when the military government issued censorship principles and regulations to make sure films did not harm “the image of the state.” The government—through the Ministry of Information—attempted to use film as one of the tools to propagate its own ideas and to obstruct the spreading of opposing ideologies.

A synopsis or brief screenplay of every feature film must be submitted to the board in order to gain permission to film, and a full version of the film has to be submitted again before it hits the box office; direct-to-DVD movies, however, need no pre-filming submission.

Phone Maw, a member of the film censorship board and the secretary of the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (MMPO), said all board members have to check every film and video for the sake of the audience. He said Burmese audiences are still not ready to consume products directly from filmmakers, as some filmmakers are still creating films that are unsuitable to watch with one’s family or are religiously and culturally inappropriate.

“We can’t create whatever we want in the name of freedom. We must take responsibility for our art,” he said.

“We will no longer need the censorship board when our country changes from all of its old systems, gets used to democracy, and has responsibility and accountability.”

A retired director from the Motion Picture Development Branch (previously known as Myanmar Motion Picture Enterprise) and a former secretary at the then-Film and Video Censorship Board, Myint Thein Pe, told The Irrawaddy that board members come from diverse backgrounds and few have a comprehensive understanding of art and films.

“The policies were good, but the people who practiced these policies were dreadful,” Myint Thein Pe said.

“They were not independent thinkers. They were controlled by fear, and that was the biggest problem,” he explained, referring to how some former board members were driven largely by a desire to neutralize content that could be perceived as harming the dignity of the country, without understanding which scenes were necessary to a film’s story.

“That fear will not disappear until the next generation,” Myint Thein Pe said.

He also explained the struggle of fostering a freer film culture in Burma, where religious and traditional beliefs are strong enough to easily censor a film.

“Film is a type of culture. But when this culture is fenced in by censorship principles like religion, tradition and ethnic solidarity, things can become very difficult for filmmakers to escape from the shadow of censorship,” he said.

Lack of Creativity

Myint Thein Pe, however, is not optimistic about the impact of relaxing some censorship regulations since 2011.

“Since censorship has eased, I have not noticed any marked improvement in the creative process. Technological improvement is an exception. But the industry keeps spinning its wheels and just does what is trendy,” he said.

Industry observers point out that the country’s current market is saturated with pirated South Korean, Thai, Chinese, and American DVDs, and that many local filmmakers simply adapt stories from foreign films rather than create original content.

Despite the sometimes-bizarre rulings—like banning bell-bottoms—the period from the 1950s to the 1970s is still viewed by many as the industry’s golden age with local filmmakers producing nearly 100 original films each year on average. The country now makes less than twenty feature films annually, and releases between 800 and 1,000 direct-to-video DVDs.

Award-winning director Kyi Soe Tun said censorship should not receive the entirety of the blame for the industry’s downfall.

“I don’t like blaming censorship. I don’t believe that films can’t be artistic within the boundaries [of censorship],” he told The Irrawaddy.

“We can create art no matter what rules and regulations exist. All we need is basic critical thinking and a conscience.”

He cited the film “Thingyan Moe”—the movie that saw its Mandalay dialect censored. Produced in 1985 under a strict censorship regime, the movie later became an iconic representation of the Burmese water festival; shown on TV every year, its significance during Burma’s biggest festival is arguably similar to the place that films like “It’s a Wonderful Life” hold during the American Christmas season.

“Despite the censors, we all know that [Thingyan Moe] is still a good film more than three decades later,” Kyi Soe Tun said. “But I have to say that I don’t like censorship interferences in that film.”

Htoo Paing Zaw Oo agrees. A newcomer in the mainstream film industry, his movie “Night” was praised by the censorship board as “artistically and technically good yet made within the boundaries [of censorship].”

The director told The Irrawaddy that the censorship board is not an impassable barrier to creating quality art but it does pose difficulties for filmmakers.

“If a filmmaker has to think about the potential of censorship while he or she is making a film, it restricts his or her artistic inspiration,” he said. “I personally think the major problem of the film industry of this country today is a lack of creativity rather than strict censorship.”

Myat Noe, a film critic and a cinematic analyst, told The Irrawaddy that any amount of censorship will inevitably impact an artist’s creative process, but it is the job of artists to figure out how to address a banned issue in an indirect, oblique and subtle way.

“The impact of [censorship] easing is apparent,” he said. “Sadly, the quality of films, especially in terms of the script, storytelling techniques and style, has not improved much.”

“If you don’t get a good script, you don’t get a good film,” he said.

Adapting to a Ratings System

Thu Thu Shein, co-founder of Burma’s first independent film festival, the Wathann Film Festival (WFF), said that the censorship board should be reformed to function as a ratings board, to limit the negative effect on filmmakers’ creativity. It could also bar underage audience members from watching violent and sexually explicit movies, she said.

“They should allow filmmakers to create art independently, and their movies can be controlled with the ratings system,” she said.

But the censorship board members disagree with the idea of a ratings system.

Thein Naing, the director of the Ministry of Information’s MPDB and the secretary of the censorship board, said that the audience is not mature enough for a ratings system.

“We can’t implement the ratings system yet,” he said. “How are we going to monitor the age of the audience? We don’t have such a monitoring mechanism in cinemas.”

However, Wyne said the government should develop a ratings system so that the audience can begin to adapt to the new labels. Without developing such a practice, the audience will never be ready, he said.

“It could be done if they wanted to do it. But they don’t want to do it so they are just making excuses,” he said.

Wyne also re-submitted his film, “Letter to the President,” to the censorship board in April, in the hopes that that the new government will not object to its plot.

Revolutionary Road

For director Htoo Paing Zaw Oo, there are other reasons behind the failure to produce films of a higher storytelling and artistic standard—the majority of movies are market-oriented and only focus on featuring famous stars rather than developing authentic stories. Moreover, he said, production companies tend to not invest significant amounts of time in the films and instead focus on simply releasing as many movies as they can.

A willingness to welcome directors from younger generations is also lacking in the Burmese film industry, according to film critic Myat Noe. “Famous actors who have great influence in decision-making processes and financiers who produce films do not want to welcome a new generation of young, film school-educated directors,” he said.

Producers simply do not trust them, he added, pointing out that these burgeoning filmmakers often understand modern and international industry trends and could potentially create different types of films.

“To my knowledge, nobody’s hiring them to make films,” Myat Noe said.

Myint Thein Pe agreed. He said the film industry needs rebels—a new generation of filmmakers with fresh ideas and concepts—to change the culture of moviemaking.

“There must be a film revolution and we have to make rebels for this revolution to happen.”