YANGON—In its latest attempt to bring to account those responsible for atrocities against the Rohingya, the UN Human Rights Council on Thursday voted to set up a body to prepare evidence for use in any future prosecution brought by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

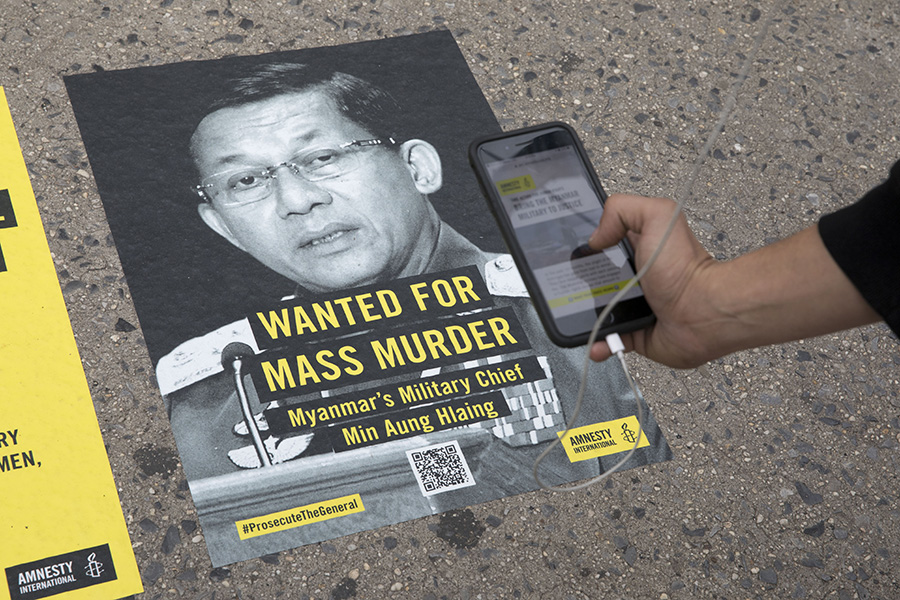

Earlier this week, the rights group Amnesty International (AI) plastered “wanted” pictures of Myanmar military chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing around New York City. The posters read: “Wanted for mass murder – Don’t let him get away with it.”

The public shaming campaign and the UN vote were the latest in a series of moves intended to ratchet up international pressure on Myanmar’s top general for his troops’ alleged atrocities against Rohingya in northern Rakhine State. In August last year, nearly 700,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh to escape security forces’ clearance operations. The operations were triggered by a series of attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on police outposts in the area. The Myanmar government has denounced ARSA as a terrorist group.

Since then, Snr-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing has faced mounting international pressure. A recent UN Fact Finding Mission (FFM) recommended that he and his subordinates be referred to the ICC for ethnic cleansing and acting with “genocidal intent” against the Rohingya. During a visit to Myanmar two weeks ago, British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt said the international community should consider referring Myanmar to the ICC over its treatment of the Rohingya if those responsible are not tried and held accountable inside the country. This was followed by AI’s poster campaign and the UN Human Rights Council vote.

In its relentless lobbying for action against the leadership of the Myanmar military (or Tatmadaw) over the Rohingya’s plight, the international community appears to be trying to exploit the issue to oust the military from Myanmar’s politics. The country’s controversial 2008 Constitution enshrines the Tatmadaw’s political role by reserving 25 percent of the seats in Parliament for military appointees and handing the military the reins of three security-related ministries.

It’s taken for granted that not everyone in Myanmar is pleased with the military’s involvement in the country’s politics. Over nearly five decades of military rule until 2011, Myanmar’s citizens watched the men in uniform turn their country from the most developed nation in Southeast Asia into one of its least developed. That’s why the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) continues to push for amendments to the charter that will keep the military out of politics. It has achieved no tangible results so far, due to resistance from the military, but the country’s de facto leader, State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, said in Singapore last month that “We shall do that through negotiation and step by step, keeping in mind our need for national reconciliation.”

By “national reconciliation”, she means establishing sufficient mutual trust with the armed forces to convince military leaders that the government can be entrusted to handle pressing national issues such as the peace process and constitutional amendment.

Is it therefore realistic for the international community to treat the Rohingya crisis—probably the country’s most controversial and militarily sensitive issue—as an opportunity to try to force the military out of politics using harsh measures?

“That’s wishful thinking and shows a lack of understanding of how Myanmar’s military officers think of themselves,” said Myanmar expert Bertil Lintner, a Swedish journalist who has covered Myanmar and Asia for nearly four decades.

Lintner said he didn’t think Snr-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing had much to fear, as the officer corps was loyal to him and would remain so even after he retires.

“No one is going to hand him over to any international court. And as long as he has the backing of powerful nations like China and Russia, he is safe,” he said.

NLD spokesperson U Myo Nyunt said outsiders who attempt to push the military out of politics are taking the wrong approach, as the military has traditionally never kowtowed to outside pressure. History shows how defiant the Myanmar military can be. Examples can be seen in its refusal to hand over power to the NLD after the 1990 general election, as well as its crackdown on the Buddhist monk-led Saffron Revolution, the 11th anniversary of which is marked this week.

“To do so [submit to international pressure] now would be a source of shame to them,” he said.

The spokesperson said trying to exploit the Rohingya crisis to oust the military from politics would be counterproductive, as most people in Myanmar stand with the military on the issue.

“Harsh measures would only turn the public against the West,” U Myo Nyunt said.

Rather than using pressure, he said, the international community should cooperate with the military to expedite the process of repatriating the Rohingya to Myanmar.

“If they do so, it would be very effective [for the repatriation process],” he said, because only the military has the ability to convince the refugees that it is safe to return.

He is not the only one calling for international engagement. In its recent report on China’s role in Myanmar’s internal conflicts, the United States Institute of Peace recommends that

Washington consider ways to both apply pressure and appropriately engage the Myanmar military in a way that empowers democratic institutions in Myanmar, moves toward resolution of the Rakhine crisis, and continues the progress of reform inside the country.

Yangon-based political analyst U Maung Maung Soe said the international community, including the UN, should focus more on pressing issues like repatriation, rather than taking action against military leaders.

“What they are doing now is sort of inflaming the military’s anger. The more they are getting pissed off, the more difficult repatriation will be,” he said.

And the military leadership is showing signs of displeasure. Snr-Gen. Min Aung Hlaing last week rejected Hunt’s request for a meeting and would not even allow his deputies to receive the minister. This was a break from the military leader’s previous approach of painstakingly explaining the Tatmadaw’s view of the Rohingya issue to nearly every international dignitary he met, insisting that his troops had followed normal rules of engagement in Rakhine. Presumably, he sees the U.K. as one of the countries lobbying for his referral to the ICC. Later that week, the armed forces chief warned against foreign interference, saying, “As countries set different standards and norms, any country, organization and group has no right to interfere in and make decision[s] over [the] sovereignty of a country.” It was his first public comment on the issue since the UN fact-finding mission released its report calling for the prosecution of Myanmar’s military leadership at the ICC.

U Maung Maung Soe expressed concern that the scenario could force the military to cling even more firmly to power—dimming hopes of its exit from politics.

“Even with the power they have now, they are being referred to the ICC. They fear they would be more vulnerable if they have no power,” he explained.

For Lintner, the most likely scenario is that Myanmar will remain under military rule for the foreseeable future. If change ever comes, he said, it will have to come from within the military.

But he said that’s not likely to happen any time soon, and even less so now while the military is under international pressure. Instead of giving up power, he added, the military will dig in, fortify its defenses even more vigorously and wait for the international criticism and condemnation to die down.

“That’s exactly what they did after the massacres of pro-democracy demonstrators in August and September 1988. And it worked then.”