YANGON — Thousands of displaced Shan have called for continued humanitarian support for refugee and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps along the Shan-Thai border.

After more than a decade of providing aid, international non-governmental organizations have announced that they will cut off food support for all six camps in the region in October, said Sai Korn Lieo, spokesperson for the Shan Human Rights Foundation (SHRF).

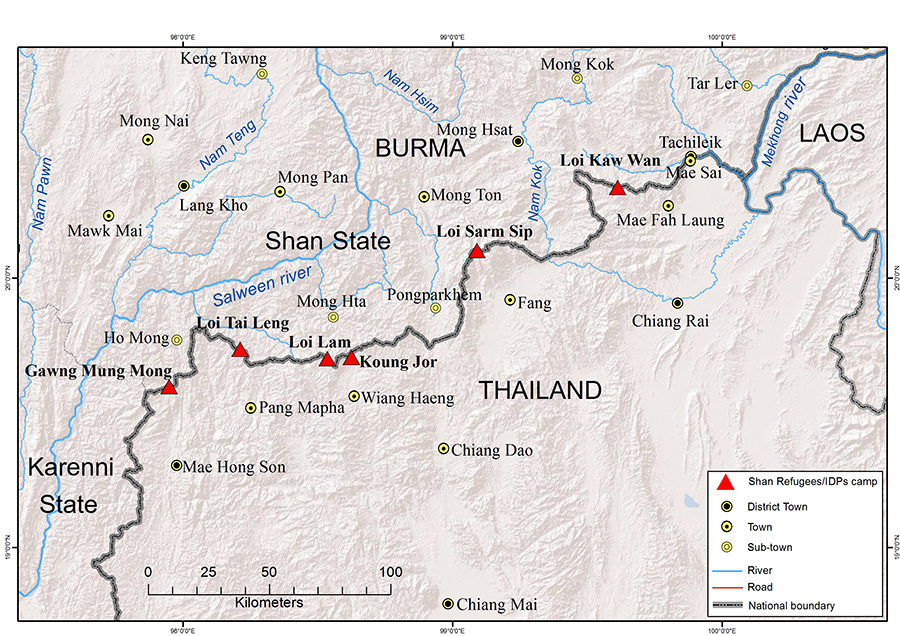

The Shan-Thai border camps—established 18 years ago—host around 6,200 displaced people, 70 percent of whom are women and children, according to SHRF. Many of the camps’ residents fled central Shan State between 1996 and 1998 due to clashes between the Myanmar Army and Shan armed groups.

Those in the camps represent a range of ethnicities, including Shan, Lahu, Akha, Wa, Ta’ang, Pa-Oh, Lisu, Karen and Chinese.

News of the upcoming cuts to aid was reported to camp leadership in April and May, after more than a decade of support; international non-governmental organizations cited progress in Myanmar’s peace process as a reason for the policy shift.

Lung Sai, chairperson of the Shan State Refugee Committee (Thailand), outlined some of the challenges faced by these communities.

“We don’t have land to cultivate. Thailand does not allow us to work. We have a water shortage in the camps. And now, the aid is going to stop,” he said.

IDPs cannot engage in traditional agriculture on either side of the border, where they live on slivers of territory controlled by the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S), situated between the Myanmar Army or militias on one side, and the Thai authorities on the other. Those in the camps rely on aid—13 kilograms of rice, as well as yellow beans and one liter of cooking oil per person, per month.

Sai Korn Lieo told the Irrawaddy on Thursday that they are urging donors to continue this support “for their survival.”

Although the RCSS/SSA-S signed the nationwide ceasefire agreement with the military and government in 2015—a key step in the current peace process—fighting continues to take place near several IDP camps over disputed territory with the Myanmar Army. There are also frequent clashes between the military and non-signatory ethnic armed groups in Shan State.

“Despite the peace process, it is still impossible for the displaced villagers in camps along the Thai-Shan border to return home, unless there is a genuine nationwide ceasefire, withdrawal of Burma Army troops, and a political settlement with the ethnic armed stakeholders,” read a statement from SHRF.

Sai Korn Lieo added that despite the existence of a peace process, “there’s still not any peace” in Shan State.

“We don’t have or have lost our national identity cards, so I don’t think we can enter Myanmar. I haven’t heard of any plans from the Myanmar government regarding long-term IDPs,” said Lung Sai.

Lower House MP Sai Thiha Kyaw of Shan State’s Mong Yai Township told The Irrawaddy that he would propose a discussion regarding a government plan for Shan State’s displaced during the upcoming parliamentary session.

According to SHRF’s report on the crisis, the future of many in Shan State is further complicated by plans to construct large hydropower dams in the region—like the Mong Ton project on the Salween River—as well as mining projects, which they say will cause further displacement.