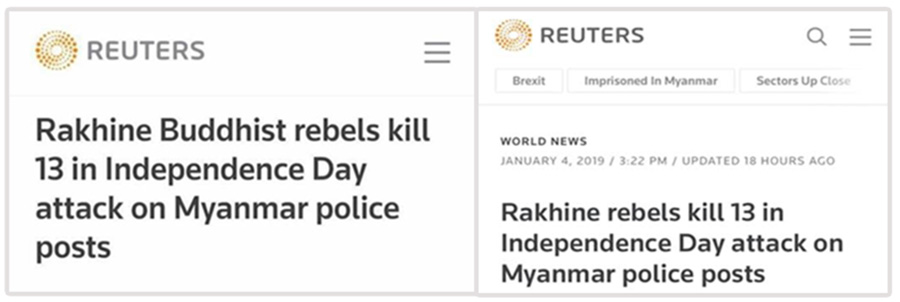

YANGON—Bowing to public pressure, soon after publishing a report on the deadly Jan. 4 attacks by the Arakan Army (AA) in Rakhine State, Reuters news agency removed the word “Buddhist” from the story’s headline and lead paragraph. The initial story was headlined: “Rakhine Buddhist rebels kill 13 in independence day attack on Myanmar police posts.”

The AA’s coordinated attacks on four border police outposts in northern Rakhine State’s strifetorn Buthidaung Township left 13 Border Guard Police officers and three AA fighters dead. Though the conflict between the Arakanese rebels and the government is essentially political, Reuters’ headline used religious terminology.

Many people disagreed with the agency’s use of the Rakhine community’s religious affiliation in the headline and the story. It’s true that the majority of Rakhine people are Buddhists. But critics voiced concern that emphasizing this in the headline of a story on the armed conflict had potential to fuel international misunderstanding of the situation in Rakhine.

In 2017, after security forces’ clearance operations against the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) in the same area prompted nearly 700,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh, international media indiscriminately mislabeled all Buddhists in Rakhine state as “violent”. With the headline “Rakhine Buddhist rebels kill 13 …”, did Reuters want to portray Rakhine people as violent? What’s more, the heading implies that if Buddhist groups are killing each other, there can be little wonder that the Buddhist majority is intolerant of Muslims.

It needs to be asked why Reuters chose to use a religious term in reference to the ethnic Rakhine. In its reports on other armed groups in Myanmar, it simply refers to, for example, the KIA as “Kachin rebels” and to the KNU as “Karen rebels”, rather than calling them “Christian Kachin rebels” or “Christian Karen rebels.” For example, a Reuters report on the death of 23 cadets killed by Myanmar Army artillery fire on a KIA training camp in 2014 referred to “Kachin rebels” in the headline, without specifying their religion.

Yangon-based ethnic affairs analyst U Maung Maung Soe openly condemned Reuters on his Facebook page, accusing the agency of religious incitement. He told The Irrawaddy that using religious references in conflict reporting could spark problems.

“Please think about the potential consequences if you say, ‘Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslim Rebels Are Fighting’ rather than saying ‘AA and ARSA’, he said.

U Maung Maung Soe was not the only person criticizing Reuters; local media experts disagreed with the agency’s decision to insert the religious issue into the news story, saying its reporting did not meet acceptable standards for what is known in the industry as “conflict-sensitive journalism”.

Media adviser U Sein Win from Internews Myanmar said that the international community’s knowledge of Rakhine State was mostly limited to issues relating to the Rohingya, adding that global audiences were largely ignorant of the ethnic Arakanese (another term for Rakhine). He assumed that Reuters had emphasized “Buddhist” in the headline in order to avoid confusion with the Rohingya, but said that as the conflict is not a religious one, the news agency should not have used the term in that way.

He explained that while it was acceptable to identify a group’s religious affiliation in a headline if the issue being reported was related to religion, it is discouraged in conflict-sensitive journalism, as conflicts can be worsened by sensational coverage. He added that an agency was within its rights to use religious descriptions in reports when they appear as part of a name, such as the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA).

“Our choice of words in a report should maintain stability and we journalists have a responsibility not to cause divisions within communities. That is the meaning of conflict-sensitive journalism,” U Sein Win said.

When asked if the agency’s removal of the word “Buddhist” was prompted by the public perception that Reuters had ignored local and religious sensitivities, the agency said via an email on Monday that, “In keeping with our commitment to the Reuters Trust Principles of independence, integrity and freedom from bias, we updated this story to clarify the context that the Arakan Army insurgency is ethnic, rather than religious.”

In fact, Reuters is not alone in using religious terminology in its reporting on the Rakhine conflict. The Wall Street Journal used an even harsher headline: “Buddhist Violence Portends New Threat to Myanmar”. In its reporting on fighting between the AA and the Myanmar Army, Al Jazeera has used terms like “Buddhist Rebels” and “Buddhist groups.”

But it is Reuters that has attracted the most attention from local netizens, as the agency has been under public scrutiny in Myanmar since last year’s arrest of two local reporters who covered a mass killing of Rohingya in Rakhine. Their arrest and reporting sharply divided public opinion. So the agency’s lack of local and religious sensitivity could further widen the divisions.

Writing on his Facebook page, Letyar Tun, who works with a media development INGO, questioned Reuters’ professionalism.

He said Reuters should have referred to the AA using the ethnic group’s own language—the Arakan Army—rather than dubbing them “Rakhine Buddhist rebels”.

“As journalists, your most powerful tools are the words you use, along with pictures and sounds. You can use your tools to build peace and understanding instead of fear and myths,” he wrote.