The revered journalist and pro-democracy champion Win Tin passed away two years ago today, April 21, 2014, at the age of 84. In this story from The Irrawaddy archive, published less than a week after his death, our photographer Hein Htet describes a post-mortem visit to the once home of the man.

Unlike my last visit months ago, the shack at No. 10 Ariaya Maggin Street is locked when I arrive. Outside the door, a plastic flowerpot hangs from the gutter, as it did before. Two purple orchids are in full bloom.

“They were his favorite,” says Ohn Than, the owner of the two-room shack in Rangoon, while unlocking the door for me. Inside, the living room is silent. The man who once lived here—a man with wavy white hair and a blue shirt, a man known for greeting all visitors and inviting them to sit down—is no longer around.

I am standing alone, camera in hand, in the former home of the veteran journalist who became one of Burma’s most prominent democracy activists, Win Tin. This is where he lived until March 12, when he was admitted to a hospital for health problems. Six weeks later, on Monday this week, he was pronounced dead due to multiple organ failure. He was 84 years old. I have come to take photographs of the place where he once spent his days.

Win Tin first moved into this wooden shack in 2008, after he was released from his 19-year prison term. In 1989, when he was first thrown behind bars due to his opposition to the military regime, the government confiscated his room in a government housing facility near Rangoon General Hospital. When he was finally freed, he had nowhere to live, so he moved into a shack in the garden of his lifelong friend Ohn Tun’s home.

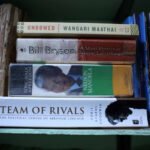

In the shack, Win Tin’s belongings appear to have been left alone since he was admitted to the hospital. At the basin in the far corner of the living room, a toothbrush and tube of toothpaste are covered with dust. So, too, are his walking sticks. His study table is partially covered with local weeklies and writing papers. His dark blue vests, which he wore over his blue shirt, hang on clothes hangers. The television set that he regularly used to watch late-night Champions League football matches is turned off. Shelves are lined with books, despite his generosity to allow friends to take any titles they wanted to read.

While taking photographs, I cannot help but imagine how Win Tin may have passed his days here. I can picture him reading books and receiving guests, from diplomats to journalists and activists, and always speaking out with sharp criticism. “I don’t trust this government at all,” he would say.

Opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who co-founded the National League for Democracy (NLD) party with Win Tin under the military regime, also came to this shack on Tuesday. After her 45-minute visit, she told Ohn Tun and his family members to keep Win Tin’s belongings as they were. “Please make sure no one takes anything,” she said.

“She said, ‘I wish I could take away the whole shack,’” Ohn Tun recounts. Perhaps she meant that she would like to convert it into Win Tin’s memorial museum.

Additional reporting by Kyaw Phyo Tha.