YANGON—While the West abandons Myanmar over the human rights crisis in Rakhine, China and Japan, understanding the value of the country’s strategic location in Southeast Asia, have done the opposite, accelerating their collaboration in a bid to get the upper hand and further their own grand plans.

Beijing and Tokyo’s strategies to connect continents and oceans with sea lanes and inland highways that will improve Myanmar’s infrastructure have the potential to revive the country’s slowing economy and position the country as a regional trade and supply hub.

Key Chinese figures have been traveling back and forth between the two countries this year to pursue Beijing’s dream of implementing the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), part of its region-wide Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A week after signing the Kyaukphyu SEZ, the vice chairman of China’s top economic planning agency pushed Myanmar’s State Counselor—who also serves as chair of Myanmar’s BRI steering committee, to move forward with projects on the ground.

Myanmar’s BRI steering committee comprises 25 members including 18 Union ministers (from ministries ranging from Home Affairs to Hotels and Tourism); five chief ministers (from Kachin, Mandalay, Rakhine, Yangon and Shan); the foreign affairs permanent secretary; and the chairman of the Naypyitaw Council.

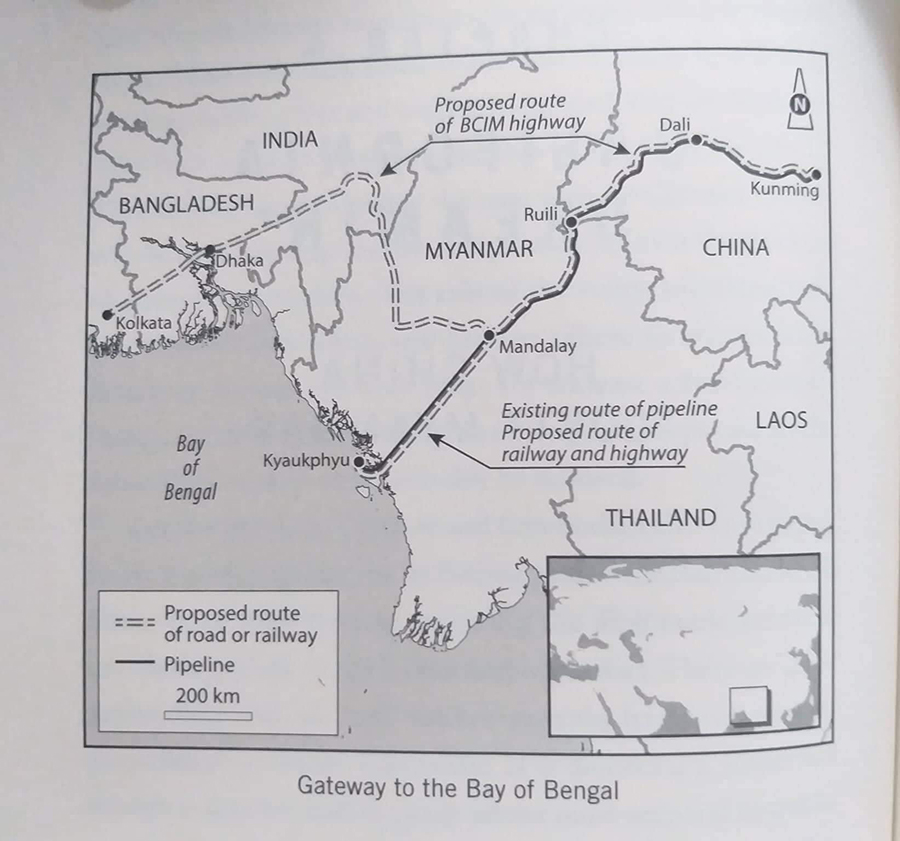

Last month, Beijing secured a long-awaited agreement to build the Kyaukphyu deep-water port in northern Rakhine State, which already serves as the terminus for twin cross-border oil and gas pipelines between the two countries. Kyaukphyu is a crucial phase in the CMEC.

According to U Set Aung, deputy minister for planning and finance, the Kyaukphyu project will contribute to the sustainable development of both countries and will also be crucial to enhancing Myanmar’s regional connectivity.

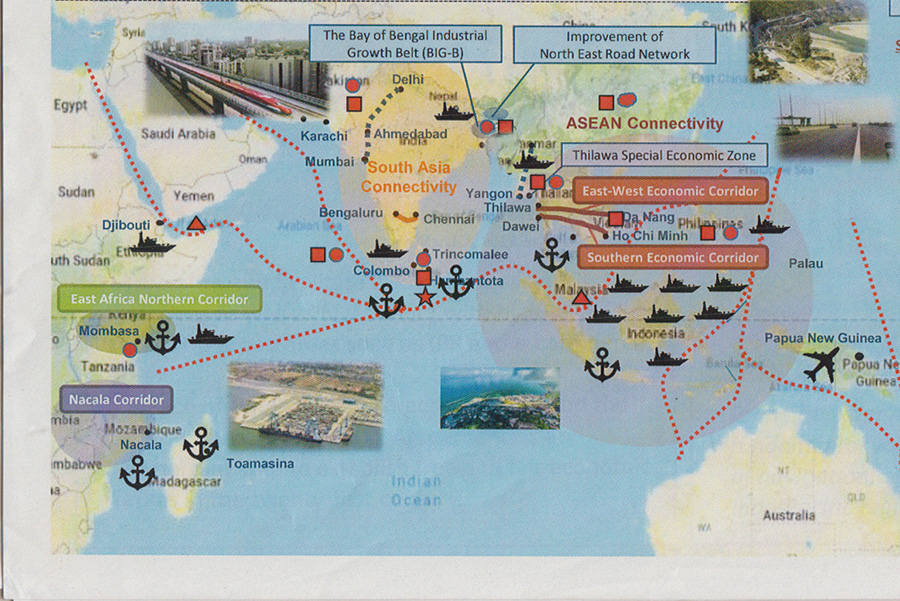

Japan has accelerated its plans for Myanmar’s first special economic zone (SEZ) in Thilawa, which received more than $1.3 million in investment from 2014-18. It is also planning to upgrade roads and bridges through two states via the East-West Economic Corridor, one of the cross-border transport infrastructure projects that form part of Tokyo’s Greater Mekong Region economic integration scheme.

After nearly six decades of isolation under military dictatorship, the government led by State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been implementing economic reforms to complete Myanmar’s democratic transition. The government has drawn up the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (MSDP), the aim of which is to align the country’s numerous policies and institutions to achieve genuine, inclusive and transformational economic growth. The MSDP also aims to improve the country’s connectivity with neighboring countries and prioritizes economic corridors under both the GMS and BRI.

Under the BRI, Kyaukphyu is seen as a potential hub for China, giving it direct access to the Indian Ocean and allowing its oil imports to bypass the Strait of Malacca. It also serves Beijing’s goal of developing China’s land-locked Yunnan province.

At a recent Union-ministerial-level planning and finance meeting, it was disclosed that the CMEC will pass through Yangon, Mandalay, Shan, Irrawaddy and Rakhine (to the Kyaukphyu SEZ). China has proposed a total of 40 projects, but the two sides have only agreed to implement nine so far. However, the meeting didn’t issue details of the projects, other than construction plans for three economic cooperation zones along the Myanmar-China border in Shan and Kachin states.

In Yangon, the multi-billion-dollar New Yangon City project is a part of the CMEC plan. A framework agreement was recently signed for the project, which is envisioned as a complex of new towns, industrial parks and urban development projects.

Myanmar has also signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with China to begin studying a proposed railway line from Muse, in northern Shan State, to Mandalay. The Muse-Mandalay line is part of Beijing’s plan to build a parallel expressway and railway line from Ruili (across the border from Muse in China’s Yunnan province) to Kyaukphyu, with a separate road running through northern Myanmar, the northeast states of India, and Bangladesh under the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC).

Within the competition between China and Japan in the Mekong Region, “vertical” integration has been driven by China, while “horizontal” integration has been driven by Japan, as Myanmar exists in the heart of Asia with China to the north and east, India to the west and ASEAN to the east and south.

While Myanmar has come under severe pressure from the international community, Japan has shown its full support, helping to solve the Rakhine crisis and also showing strong disagreement with the EU’s consideration to withdraw trade preferences, which would hurt ordinary people in the country. In recent months, Japan announced its Tokyo Strategy 2018, aimed at promoting quality infrastructure development in countries along the Mekong River to counterbalance China’s growing influence in the region via the BRI.

However, Japan’s quality infrastructure projects in the Mekong Region date back to the early 2000s, initiated by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA has spent trillions of yen to improve economic integration in the Greater Mekong Region with a network of land and sea infrastructure routes between the countries. It emphasizes regional connectivity, which is focused on both industrial and physical infrastructure such as roads, telecommunications and power transmission lines.

“The rapid rise of China is one major factor in JICA’s decision to increase infrastructure development assistance in the Mekong Region,” said Tetsuji Iida, an adviser to the Planning and ASEAN Partnership Division of JICA’s Southeast Asia and Pacific Department.

Since the 2010s, Myanmar has opened up to the world and also joined in the full scope of GMS cooperation that has opened a new front in China and Japan’s rivalry in economic diplomacy.

Within Japan’s grand plan, Myanmar sits on two major economic corridors: the East-West Economic Corridor connecting Vietnam’s Dong Ha City with Yangon’s Thilawa Special Economic Zone (SEZ) via Cambodia and Thailand, and the Southern Economic Corridor connecting central Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand to the Dawei SEZ in southeastern Myanmar.

State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has claimed that Myanmar will benefit from over 16 bilateral projects and 100 multilateral projects as part of the Mekong-Japan cooperation.

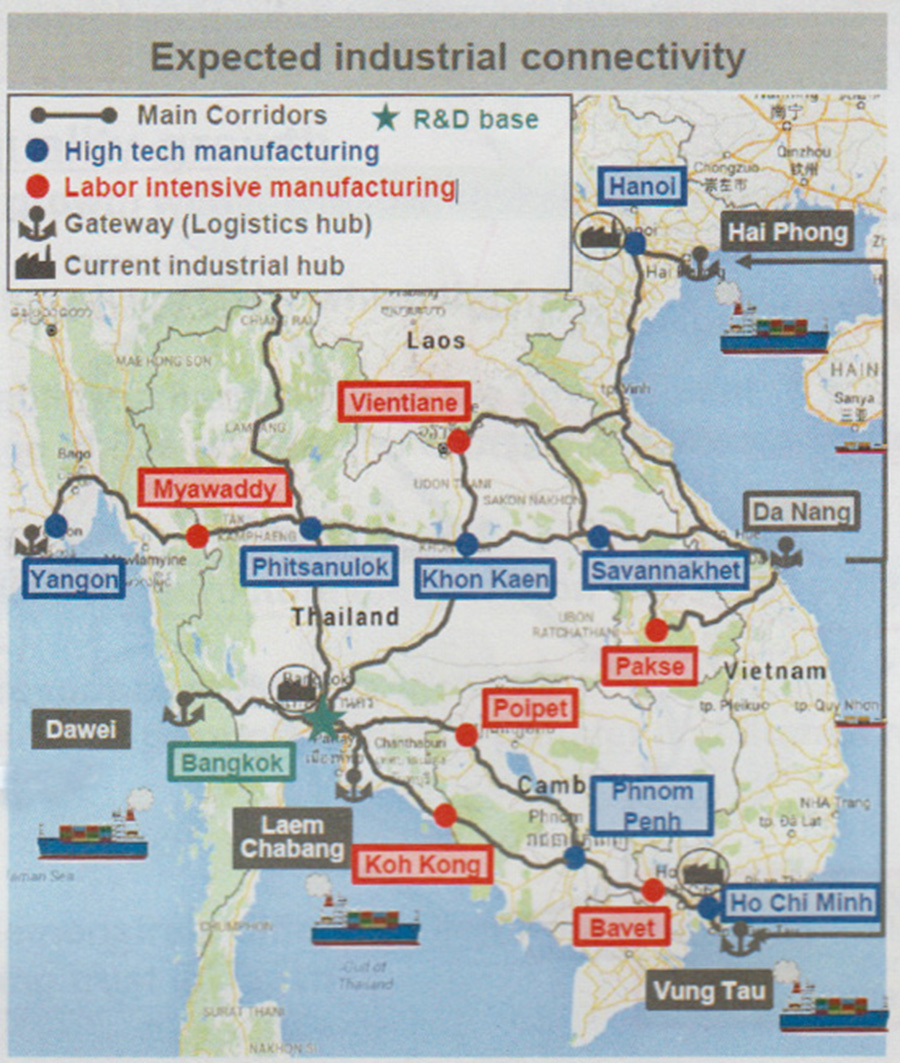

Japan’s grand plan aims to improve connectivity between Bangkok and Yangon along the East West Corridor. The corridor will help businesses based in Bangkok extend their supply chains to Yangon (at the Thilawa SEZ).

JICA is looking to build an inland highway as a transport shortcut from Thilawa to Bangkok. Transportation routes from Singapore currently runt to a combined length of 4,000 km and take 21 days to negotiate. On the East-West Corridor, the Myanmar section does not function as an international highway due to bottlenecks such as one-way traffic, a lack of paved roads, traffic difficulties in the rainy season and weight limitations.

JICA plans to shorten transport time by constructing three bridges in Karen and Mon states—the Gyaing-Kawkareik Bridge, the Gyaing-Zathabyin Bridge and the Atran Bridge—as a part of the East-West Economic Corridor. It expects to take one-and-a-half days to transport goods over 870 km from Thilawa to Bangkok. JICA expects loans for the project to amount to about 33.8 billion yen and that the project will be complete by 2023.

Japan pledged about 800 billion yen (US$7.03 billion) in 2016 in public and private support over five years, including for urban development in Yangon, and roughly 260 billion yen for the Mandalay-Yangon rail modernization project. JICA agreed to provide 6 billion yen in grants to develop a major port in Mandalay that will connect the two cities by river. The plan includes the construction of a new pier and cranes to handle freight.

According to Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, Tokyo also plans to construct the Hanthawaddy International Airport near Bago city around 80 kilometers north of Yangon. In May, Transport and Communications Minister U Thant Sin Maung said that although Japan wants to start the project as soon as possible, Myanmar is considering the investment amount. However, according to a Japanese newspaper report in June, both sides agreed to go ahead with the project, which has a total estimated cost of $1.5 billion and is slated to be completed in 2020.

On the Southern Economic Corridor, the Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ) is crucial for Japan’s GMS connectivity, which will link central Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand to southeastern Myanmar. The Dawei SEZ is an $8-billion project in Tanintharyi Region that includes a deep seaport, set to be Southeast Asia’s largest industrial complex. In November, Myanmar and Thailand signed an agreement to upgrade a highway linking their border with the Dawei SEZ.

According to Dawei SEZ Management Committee Chairman U Tun Naing, JICA has been conducting a full phase master plan for the deep seaport project, including setting up an electrical grid, basic infrastructure and buildings. The primary stage of the project will jointly be implemented by Myanmar, Thailand and Japan, according to Ministry of Commerce.

Prof. Manabu Fujimura of the College of Economics at Tokyo’s Aoyama Gakuin University, an expert on economic corridors in GMS, told The Irrawaddy that Myanmar’s economic landscape is basically divided into two parts—Chinese economic influence in Myanmar will continue to extend from Muse (in Shan State on Myanmar’s border with China’s Yunnan province) to Mandalay and “upper Myanmar”, while Japanese and Thai economic influence would extend from Myawaddy (in Kayin State, on the border with Thailand’s Tak province) to Yangon and “lower Myanmar.”

Naypyitaw believes foreign direct investment (FDI) offers a shortcut by which Myanmar can catch up to its neighbors and the rest of the global economy, but experts suggest the country needs to make efforts to improve the business environment by engaging in continuous reform—while also making an effort to balance two giants while not pitting one power directly against the other.

Experts said the evidence showed that Japan wants to counter China’s economic and political forays into Myanmar, and that Japan’s role has become increasingly important as the West turns its back on Myanmar due to the crisis in Rakhine State and human-rights abuses in the country.

Longtime Myanmar observer Bertil Lintner told The Irrawaddy, “Myanmar would need some very skilled diplomats to deal with this issue, because the country is rapidly becoming a pawn in a geopolitical game that goes far beyond ports and economic zones. It’s about power games in the region where countries such as Japan and India are trying their utmost to contain China’s growing influence in Myanmar.”

Accepting aid from Japan is less risky than taking Chinese assistance, which usually comes in the form of loans and credits, which can turn into what’s known as a “debt trap”. If the loans can’t be repaid, China seizes the asset, as it has done in Hambantota in Sri Lanka. Japanese aid comes with fewer strings attached. But given the rivalry between Japan and China, Myanmar should expect a lot of Chinese pressure (political, economic, support for armed groups) if it accepts aid and assistance from Japan, Lintner added.