Aung San Suu Kyi’s mother is not as well-known as her father, but her influence on Suu Kyi’s life should not be overlooked. While Suu Kyi inherited much of her looks, her intellect, and temperament from her father, it was her dutiful and upright mother, Daw Khin Kyi, who raised her.

When I first interviewed Suu Kyi, I deliberately asked her about her mother several times, because so much had already been written about her father but very little about her mother. What attributes did she share with her mother? “A sense of duty,” she said instantly. After some thought, she added, “Discipline… courage… determination… I think I get those qualities from both my parents.”

Her mother was a remarkable woman, she said—very strong, very strict. “She brought me up as she thought my father would have. Her strength was above normal. Sometimes I think by nature she was braver than my father. I think my father, like me, had to learn to be brave. My mother was afraid of nothing.”

Her mother’s story begins in the Maungmya area, a rice-farming and fishing area in the southern Delta. Khin Kyi was the eighth of 10 children and affectionately known in her family as “Baby.” She started out in local school, but was considered bright enough to be sent by her family to get a better education at the Kemmendine Girls’ School.

The school had been started by Baptist missionaries in the 1800s and was open to all ethnic groups. Khin Kyi did well academically, but was not able to gain admission to Rangoon University. She had her heart set on getting a college education, so she persisted and was able to gain entrance to Morton Lane Teacher Training College, another Baptist School, in Moulmein.

Khin Kyi returned to her hometown to teach at a government school, but soon became restless in the sleepy provincial town. Two of her older sisters had become nurses, so she went to Rangoon to be trained as a nurse at the General Hospital, an impressive three-story facility built in the Victorian style by the British, with red brick walls and distinctive yellow trim.

Khin Kyi learned fast and gained a reputation as a can-do nurse. She was the kind of woman who did not blanch at the sight of a soldier with an arm cleaved to the bone by a machete. She stayed calm and on task even while a pregnant woman was shrieking with pain in delivery and hemorrhaging.

Even in those early days, Khin Kyi showed an interest in advancing the roles of women that would continue the rest of her life. She joined the Women’s Freedom League, which promoted women’s rights. She also transferred to a maternity hospital for a while, to gain an extra credential in midwifery. She was so valued for her skilled support in operating rooms that she was persuaded to return to the General Hospital just as war broke out in 1941.

One busy day, a cranky patient named Aung San was admitted to the hospital. The general was exhausted and had contracted malaria while helping the Japanese take over Burma. He was only 27, but he had already gained the reputation as a hero and was serving as minister of defense. The senior staff at the hospital decided that it would not be proper to assign one of the trainees to someone of his stature, so they assigned Khin Kyi, one of the most respected members of the staff, to tend to him.

She made a point of wearing a cheerful flower in her hair every day and insisted the headstrong general follow the doctor’s orders to the letter if he wanted to get well enough to return to his post. It was just the kind of tough love that Aung San needed. He not only recovered, he fell in love. It was a rare personal detour for him. He had only recently declared to his military colleagues that it would be better for true patriots to be castrated “like oxen,” rather than risk romantic affairs that would distract them from their mission. Then, he got distracted himself . . .

Marriage

The wedding was almost called off at the last minute. Aung San’s Japanese officers feted him with an all-night bachelor party of carousing to make up for his years of abstinence. The morning before his wedding day, he staggered home half-drunk with a couple of young beauties in hand. Khin Kyi, who was a tea-totaling Baptist, got word and was not amused. She told him she was calling the wedding off. Aung San swore he would never get drunk again. She accepted him at his word and forgave him. They were married on Sept. 6, 1942, and he kept his promise . . .

Aung San was under enormous pressure during their first years of married life. Publicly, he was serving his Japanese bosses as minister of defense. Privately, he was looking for a way to escape Japanese domination. He was determined to keep Burmese independence hopes alive. Aung San began secret meetings with the British. Had his efforts been discovered, he would have been shot by the Japanese for treason. His wife became his trusted confidante and refuge.

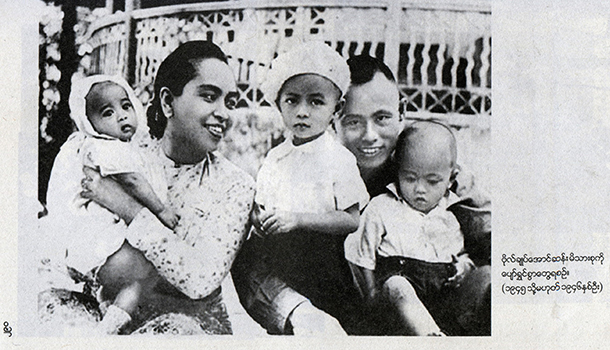

By the time the war ended, the family had settled into a two bedroom house at 25 Tower Lane.

The picturesque wooden structure had a reception room downstairs, where Aung San could meet with important officials. His home was always open to visitors, who could come by to talk with him at any time . . .

Aung San liked to come home for lunch to see her and the children. He was often away tending to government matters, but when he was at home, the couple enjoyed typical domestic life in the evening. She mended and embroidered. He read. He was quite content with his wife: She humanized him.

When he traveled, Aung San took his wife with him as often as he could . . . She knew her presence allowed her husband to cope with the pressure he was under . . .

Tragedy

On the day he was assassinated, Aung San had hugged his children goodbye and headed off to work, sticking to his schedule despite warnings of danger. He had received word three days earlier that a plot against him was afoot, but he left home that day with a smile for his children. His much-wounded body was taken to Rangoon General Hospital only hours later.

When his wife received word about the attack, she rushed to the hospital, the same red-brick building where she had helped save so many lives. But it was too late to help her husband. According to reports, blood was still oozing from his wounds as she gently cradled his head in her lap. She sat silent for a long time, too deeply stunned to weep. Then, drawing on her skills as a nurse, she gently wiped away the blood and cleaned her husband’s wounds so his body could be prepared for display for mourners. Photos taken while his body lay in state show the widow Khin Kyi sitting by the side of the coffin in a plain wooden chair, her shoulders slumped in fatigue and grief. Thousands filed past his open coffin for weeks on end . . .

Moving On

Khin Kyi could not spend the rest of her life looking back. There was the pressing problem of how to support three children. A small honorarium had been awarded by the new government to each of the murdered cabinet ministers’ wives, but it was not enough to provide for ongoing expenses and the children’s education. Khin Kyi quietly made contact with the Rangoon General Hospital to see if she might resume her nursing career. But by then, Aung San’s old college classmate U Nu was serving as prime minister. He thought a more dignified position should be found for the widow of the country’s fallen leader.

Khin Kyi was named the director of the National Women and Children’s Welfare Board. As a former midwife, she was well acquainted with the difficulties that women faced in Burma and was drawn to the idea of helping them. She was subsequently elected a member of the first post-independence Parliament, helping fulfill the dream her husband had fought for. And in 1953, she was appointed Burma’s first minister of social welfare. Khin Kyi became known as an adept administrator and was often commended for her highly disciplined management skills. Her kitchen table had once again become a sounding board for political talk, only now she was presiding.

After her husband’s death, Khin Kyi tried to establish a sense of normality for her children. She made sure they honored their father’s memory and understood they had a civic obligation as his children.

Yet Khin Kyi’s efforts to stabilize her children’s lives were interrupted by another tragedy in the spring of 1953. Her second son, Aung San Lin, who was Suu Kyi’s closest playmate, was drowned in an accident at their home on Tower Lane.

When word reached Khin Kyi, she was shocked and stricken once again. She stoically decided it was her duty to stay at her desk and finish her work before leaving to tend to yet another unfathomable family tragedy. Some people found that unusual, but they didn’t understand Khin Kyi’s deeply rooted sense of responsibility. And the pain of coming home to a dead child.

After Aung San Lin’s death, Prime Minister U Nu made it possible for Khin Kyi to move the family away from the house on Tower Lane and its mixed memories. Another house was found at an address that would later become famous: 54 University Avenue.

A steady stream of distinguished figures made their way to Khin Kyi’s home and had strong influence on the widow’s children as they grew older. U Myint Thein, a distinguished chief justice, was a loyal family friend. U Ohn, a journalist who had known Aung San and had served as ambassador to the Court of St. James and Moscow, brought Suu Kyi books and gave her long lists of books to read in English and Burmese . . .

The story is told that young Suu Kyi had such an inquisitive nature that she would pester her mother with questions when she came home from work. Her mother, no doubt sensing her daughter wanted attention, made sure to answer every question. “Never once did she say, ‘I’m too tired. Don’t go on asking me these questions,’” Suu Kyi would recall later.

Though she was a caring woman and a convivial companion with her friends, Khin Kyi was a no-nonsense taskmaster with her children. At times when she would talk about her upbringing, Suu Kyi would say she had a very Burmese relationship with her mother, which meant her mother did not discuss personal problems with her. “Parents don’t do that in a Burmese context. There is a certain reserve between the generations. Mothers of my mother’s generation just don’t have heart to heart talks with their daughters.” Her mother had been “very strict,” she acknowledged, perhaps too much so, but that discipline had often stood her in good stead in many of life’s unpleasant and unpredictable twists.

In 1960 Daw Khin Kyi was appointed ambassador to India, becoming Myanmar’s first woman ambassador, and the family moved to New Delhi. She stepped down in 1967 and returned to live a quiet life in Yangon where she died aged 76 in 1988.