There is no shortage of coverage in local as well as regional media of the ongoing armed conflict in Myanmar’s Kachin State in the north, the activities of the heavily armed United Wa State Army (UWSA) in the northeast or the still volatile situation in areas of Kayin State along the border with Thailand. However, hardly a word is written about the host of armed rebel groups that are active in some of the country’s wildest and most remote mountain ranges which form the more than 1,600 kilometer-long border with India. Yet, this is where the rivalry between Myanmar’s two mighty neighbors, India and China, has often played out and where there is potential for even more trouble in the future.

In the mid-1950s, a rebellion broke out among ethnic Naga tribesmen in India’s northeast. Being a predominantly Christian tribe of Mongol stock, they did not feel that they belonged to India and demanded independence. Not surprisingly, they received support from India’s arch-enemy Pakistan and training facilities were provided in what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. But more significantly, much more aid came from China.

In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India after a failed uprising against the Chinese who had invaded his homeland, Tibet. Asia’s two giants were on a collision course and, three years later, China attacked India and a short but fierce war was fought along a disputed border in India’s northeast.

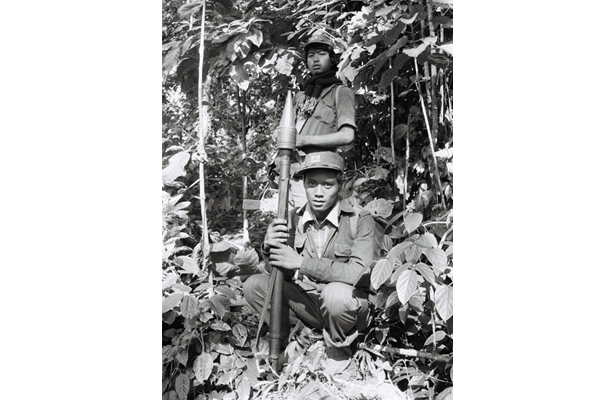

From 1967-76, nearly 1,000 Naga rebels trekked from northeast India through northern Myanmar to China, where they received military training. They were sent back to India equipped with assault rifles, light machine-guns, rocket launchers and other modern Chinese weapons. The Naga were escorted by rebels from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), which, in return for their services, kept some of the Chinese weapons.

Various other insurgent groups in India’s northeast also sought Chinese assistance. In the early 1970s, about 200 Mizo rebels—a tribe then fighting for self-determination in what is now the state of Mizoram—were trained in China; in 1976, a group of insurgents from the Indian state of Manipur made it to Tibet, where they received political training and some military instruction; and in the late 1980s, rebels from the state of Assam attempted to reach China through northern Myanmar, but ended up staying in areas controlled by the KIA—which trained some of them in guerrilla warfare.

It was clear the rebellions in India’s northeast were not solely an internal affair and that Myanmar, the land in the middle of the two regional powers, would inevitably be drawn in. This became even more evident in the 1970s when the Indian army managed to drive the Naga rebels out of their bases on the Indian side of the border. They regrouped in the rugged Naga Hills of the northern Sagaing Region. There, beyond the reach of the Indian army, they could launch cross-border raids into India.

Myanmar’s military, preoccupied with ethnic insurgencies elsewhere in the country, paid little attention to the Indian Naga who linked up with a group of Naga in Myanmar led by S.S. Khaplang. Manipuri as well as Assamese rebels also sought sanctuary on the Myanmar side of the border.

The only fall-out came in 1988 when the Naga from Myanmar, simply tired of being treated as serfs by their Indian cousins, drove them out of the area. The National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) then split into two factions: the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Khaplang (NSCN-K), led by Khaplang, and the National Socialist Council of NagalimIsak-Muivah (NSCN-IM), the Indian faction led by Isak Chishi Swu and Thuingaleng Muivah which adopted the name Nagalim, a new term for a “greater Nagaland” encompassing the state of Nagaland as well as most of Manipur, a chunk of Assam, and the Naga Hills of Myanmar. In July 1997, the NSCN-IM entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Indian government and in 2001, the NSCN-K did the same. In April 2012, NSCN-K also struck a ceasefire deal with the Myanmar government, making it the only insurgent group to have ceasefire agreements with the governments of two sovereign states.

But none of this means that the conflicts are over. Hundreds of rebels from various outfits in Manipur as well as the once powerful United Liberation Front of Asom [Assam] (ULFA) are based at Khaplang’s headquarters at Taka near the Chindwin River, north of Singkaling Hkamti in Sagaing Region. As late as December 2011, the Indian journalist Rajeev Bhattacharyya, who had trekked to Taka, observed ULFA forces taking delivery of a major consignment of weapons that most probably had been smuggled to the base from China. According to other sources, there is a booming trade in weapons acquired along the Sino-Myanmar frontier that are smuggled via Mandalay and Monywa to the Indian border. Old stocks from the UWSA’s vast arsenal of weapons and other military equipment have also been found in areas along the Indo-Myanmar border.

In late 2012, it emerged that the Myanmar army had obtained Swedish-made 84mm Carl Gustaf rocket launchers most probably supplied by India and intended for use against the ULFA and other Indian insurgents. They were instead employed against the KIA and a major scandal ensued during which questions were raised in Sweden’s parliament and the Indian ambassador in Stockholm was summoned by the Swedish foreign ministry for an explanation. Ultimately, India submitted a report stating that the weapons, which according to their serial numbers had been delivered by Sweden to India, had not been transferred to Myanmar through conventional channels, and New Delhi promised the Swedes that it would not happen again. For years, India has urged Myanmar to close down the camps that insurgents have established inside Myanmar’s Sagaing Region, but to no avail. It is clear that fighting India’s rebels is not a priority for Myanmar’s military.

And China? When ULFA commander Paresh Barua is not inspecting his troops at the Taka camp, he is in China. Obtaining weapons there does not seem to be a problem. Beijing appears to reason that if India can shelter one of its main enemies, the Dalai Lama, then Barua is welcome to stay in China. The situation promises to become even more entangled as the NSCN-IM continues to express frustration over the direction that 17-year-long negotiations with Indian authorities are headed. Barred from entering Khaplang’s area, NSCN-IM cadres in October this year were reported to have been scouting the hills east of Manipur for potential new sanctuaries in anticipation of a breakdown in talks.

New Delhi, of course, wants to see peace established along its entire border with Myanmar so it can implement its so-called “Look East Policy”—aimed at linking India with the booming economies of Southeast Asia. Myanmar’s Wild West may be almost forgotten in today’s discussions about the country’s ethnic issues, but the number of armed groups in the area with conflicting agendas makes it the country’s messiest frontier.

This article first appeared in the November 2014 issue of The Irrawaddy magazine.