Shortly before daybreak on the last day of 2017, San Zaw Htway, a Myanmar artist famous for his collages made from recycled plastic bags and also a former political prisoner, succumbed to a liver ailment in a Yangon hospital. Known for his humility and the promotion of his collage techniques among children, including those in internally displaced person camps, the 44-year-old had been diagnosed with advanced liver cancer brought on by the dire prison conditions he endured as a political prisoner and poor healthcare following his release. Here is his profile, published in the October 2014 edition of the Irrawaddy Magazine.

YANGON — Give him plastic bags of any color, and this former political prisoner will turn them into a work of art.

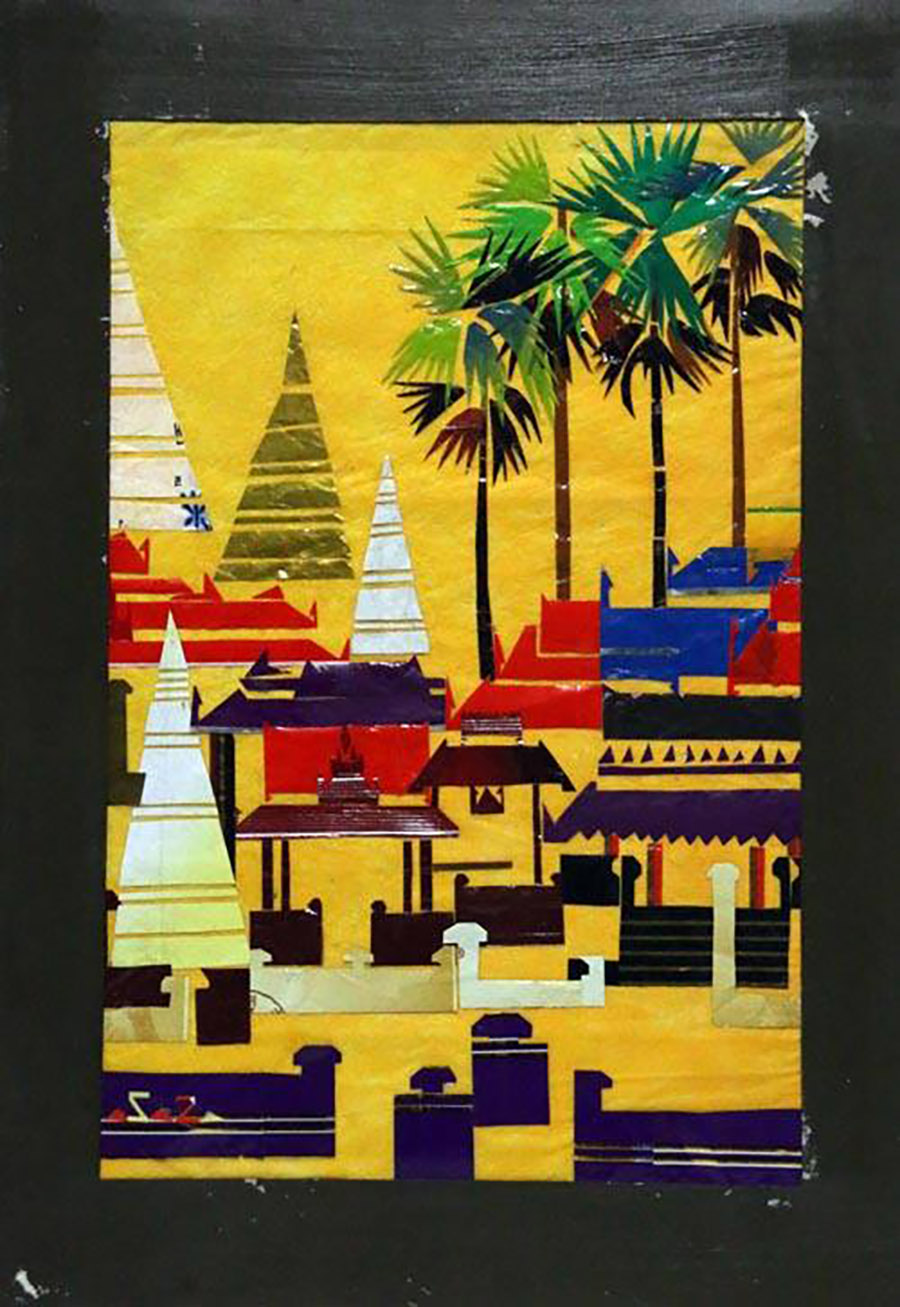

Instead of acrylic paint and brushes, San Zaw Htway opts to work with not only plastic bags, but also cardboard, instant coffee packets and other recycled goods. He taught himself to make painting-like collages with these materials while he was serving time under the former military regime.

“They’re all I need,” boasted the 40-year-old, pointing to scissors and adhesive containers littered across the floor of his studio in Rangoon. In one corner of the second-floor studio sits of a pile of smoothed plastic wrappings that otherwise would have been destined for a garbage can.

Since his release from prison in 2012, San Zaw Htway has held five solo shows in Burma, in addition to teaching his collage techniques to orphans and children living with HIV.

Now his work is gaining international attention. He has been shortlisted for the 2014 Artraker Award, which recognizes artists who are making a difference in highly challenging environments. The works of 12 candidates from 10 countries, including Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, will be exhibited from Sept. 18-25 at London’s a/political gallery.

“Being shortlisted means a lot to me because recycled collage art is still not well embraced in Burma,” said San Zaw Htway at his home, while preparing for his trip to the capital of England.

“Despite my access to paint and brushes now, I still stick to recycled collage art because it’s environmentally sustainable and I want the art trend to develop in Burma,” he added.

Painting was a childhood hobby for San Zaw Htway. When he was sentenced to 36 years in prison for his anti-government political activities in 1999, he was only a college freshman majoring in history. He spent 13 years in prison, during which time he was put in solitary confinement and he went on hunger strikes.

Burmese prisons are notorious for their squalid conditions and restrictions on prisoners’ rights, with even reading and writing prohibited. San Zaw Htaw said he saw art as a way to defy prison authorities. “I intentionally did it to show them that they can’t control everything in our lives,” he said. “But the problem was how to make it happen, since painting materials were not allowed.”

The student activist decided to make collages with materials within his reach. When his family sent him foods wrapped in plastic bags, he turned the bags into a canvas on which he plastered colorful cuttings from instant coffee packets and shampoo sachets. He scavenged prison garbage cans for plastic sheets in colors that caught his eye. He washed them, smoothed them out and applied them onto the makeshift canvas with the help of a smuggled scissor and glue.

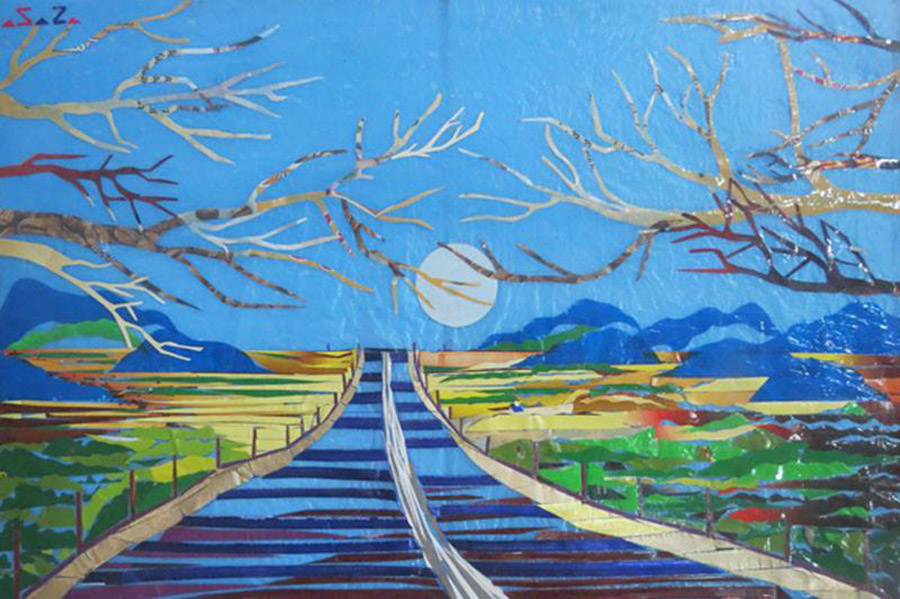

Working late at night under the faint glow of a light bulb that dangled on the ceiling of the corridor outside his cell, he was careful to hide his work from prison authorities, taking days to finish a single collage. He produced portraits of Burmese democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi and collages of peacocks, the emblem of Burmese student and democracy movements. Some of his works reflected his longing for freedom, including “Blue Moon on the Highway,” one the three collages that have been chosen for the exhibition in London.

“I was lying awake one night in 2009 and I heard the occasional swishes of buses on the highway outside the prison. I felt a surge of longing to be on one of those buses, so I poured out my feeling onto the collage,” he said.

Htein Lin, a prominent Burmese contemporary artist and another former political prisoner, said San Zaw Htway’s nomination for the Artraker Award and his participation in the exhibition would be a source of pride for Burmese artists and their country.

“I like his recycled artwork, not only for its promotion of environmental sustainability, but also for its reflection of an important message behind all forms of prison artwork: You can lock up our bodies, but not our emotions and our creativity,” he said.

Apart from being a collage artist, San Zaw Htway is a counselor for former political prisoners and their families. Earlier this year he joined a training program—organized by the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) with support from Johns Hopkins University—and now he offers counseling sessions five days per week.

“As a former political prisoner myself, I know very well to what extent we and our families have been mentally affected by what we faced for years. Counseling is one of the best ways to cure their traumas,” he said.

When asked how he felt to be participating in the exhibition in London, he said he was happy.

“My prison experience has taught me that no matter how dire the situation is, there is a way to achieve what you want to do,” he said. “That is my message to anyone who sees my art.”