YANGON — During his time in jail from 1998 and 2004, prominent artist Htein Lin used white prison uniforms as a canvas and turned soap and cigarette lighters into other works of art. He has made plaster molds of the arms of former political prisoners like himself to tell their stories.

Now, for his latest project, the artist is taking on the controversial subject of “htamein,” or women’s sarongs.

In Myanmar, there is a longstanding superstition that the clothes covering a woman’s lower half are “unclean” and cannot mix with men’s garments. The belief holds that women’s clothes, htamein in particular, should never be washed with the clothes of men or be hung in front of the house or higher than men’s garments. Men should never pass under a laundry line of women’s clothes.

Should any of these things come to pass, the thinking goes, the men will lose their “hpone,” their spiritual power or strength. A wife is considered a bad spouse if she washes her clothes together with her husband’s.

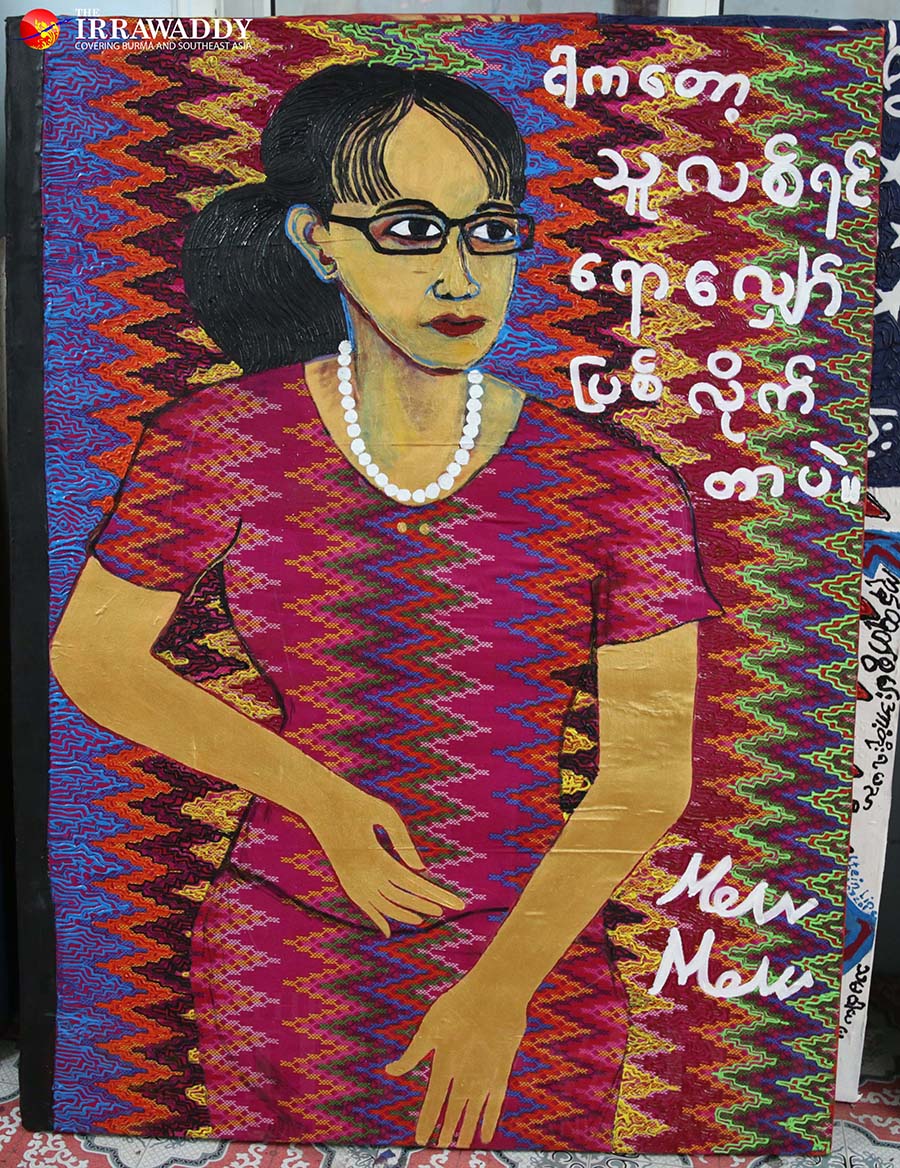

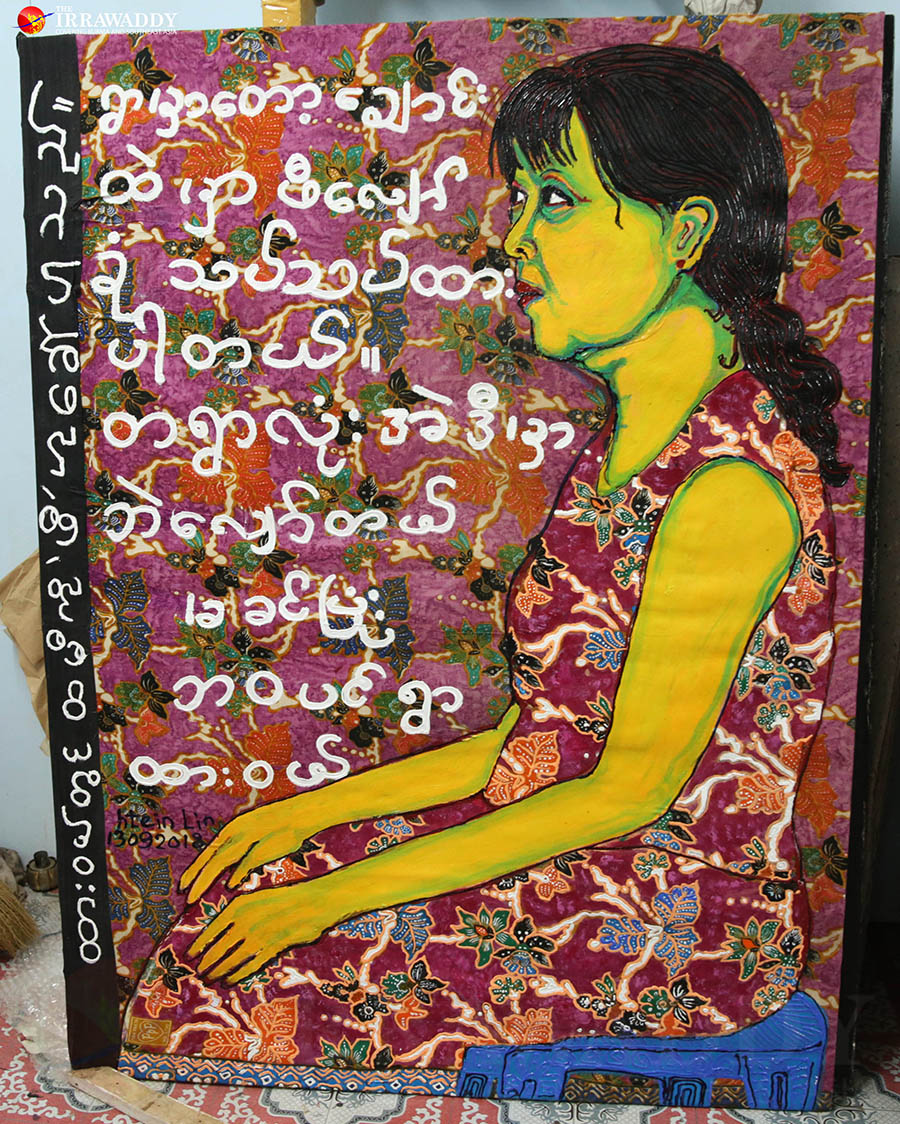

Since last month, Htein Lin has been inviting women to take part in his new project by asking them to donate their old sarongs, on which he paints their portraits and the women write down their thoughts on the superstitions surrounding women’s clothes.

Htein Lin said he wanted to find out how prevalent these superstitions still were and whether they were more common among men or women after seeing some of his friends land in trouble with their in-laws and one even be divorced by her husband for breaking the taboos.

The superstitions surrounds htamein are believed to stem from ancient legends in which the male heroes are assassinated after losing their powers because they unwittingly passed under a woman’s sarong.

The country’s most powerful institution appears to be under their spell even today. Htein Lin said the military still takes htamein seriously. He cited the 2015 case of a young woman who was convicted of criminal defamation and sentenced to six months in jail for sharing a Facebook post comparing the color of new military uniforms to the htamein of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

“If it were compared with a shawl or some cloth, it wouldn’t have been a problem for them,” the artist said.

Htein Lin doesn’t believe in the superstitions himself. He does not wash his clothes separately from his wife’s or use a different laundry basket.

He cited the comments on the subject of prominent monk Ashin Nandamalabhivamsa, who said that a man who walks under a laundry line of women’s clothes will lose his strength not because the sarongs wield genuine power but because of his obsession with the fear that they do.

He claimed that the aim of his project, titled “Skirting the Issue,” was not to end the taboo but to stimulate discussion about it.

“It is not a revolutionary idea. It is not a feminist movement. It’s just an art movement. I just want people, through this project, to reconsider” he said.

Since he started work, men and women alike have shared their thoughts on the project on the artist’s Facebook. Some of the women said they don’t believe in the superstitions; others said they do and fear a misstep could put their husband and sons in danger.

A woman from Tanintharyi Region who took part in the project wrote on her sarong that all the women in her village still wash their htamein in a separate, designated spot.

Yangon-based filmmaker Shin Daewe, who also took part, said the project was a chance for her to speak out against the superstitions, something she found hard to do day to day in the face of so much persistent belief. She said her husband shared her thoughts on the issue.

“Htamein is just some cloth to me,” she wrote on her sarong. “It’s ok to wash it together with my husband’s clothes.”

But Shin Daewe said she has received little support from friends and that the project has also made her realize just how prevalent the superstitions remain.

“I hope this project will get people to start rethinking their beliefs,” she said.

As part of the project, Htein Lin also plans to construct a tunnel-like sculpture made from women’s old sarongs, to exhibit along with the paintings. It will be up to the audience — the men especially — whether to pass through.